LCMS “snowflake” families bring children out of frozen limbo through embryo adoption

It happened on March 4 and again on March 6: two separate and unrelated “black swan” events — silent catastrophes that their respective institutions say should never have happened and could not have been foreseen.

On March 4, at the Pacific Fertility Center in San Francisco (though personnel there didn’t begin notifying clients for seven days), a liquid nitrogen freezer failed. As many as 2,000 frozen eggs and embryos “may have” been “compromised.”

Two days later, the news began to break that a similar “catastrophic failure” had occurred at the University Hospitals Fertility Center in Cleveland, Ohio. At final count, 4,000 frozen eggs and embryos were lost.

Even in a world in which embryos are seen only as potential human beings, these events are tragic. Would-have-been parents, including cancer survivors whose only chance at biological parenthood is now gone, are lining up to sue. Even celebrity lawyer Gloria Allred is getting in on the action.

For Christians who believe that life begins at conception and hold that these “compromised” (that is, deceased) embryos were once tiny, helpless, fully human children, the news is even more heartrending.

Yet even so, the outrage was muted. After a few days, the story drifted quietly out of both the news cycle and the public consciousness. It’s surprisingly easy, it would seem, to pretend that embryos are nothing more than clumps of cells — easy, that is, until you meet someone like Hannah Strege.

A unique beginning

Hannah Strege is a 19-year-old college freshman with a brilliant smile, big dreams of becoming a social worker — and an origin story that’s kept her in the public spotlight since she was no bigger than a grain of sand.

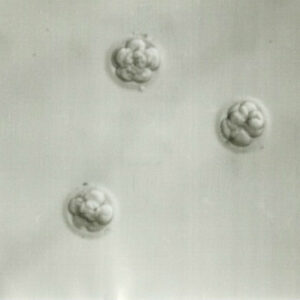

Life began for Hannah Strege, as it now does for tens of thousands of children every year, in a laboratory dish, where she was one of more than 20 embryos created during a routine cycle of in vitro fertilization (IVF).

This popular treatment for infertility combines male sperm with female eggs in a controlled environment before introducing one or more viable embryos into a woman’s womb. To increase the odds of a successful pregnancy, doctors often create many more embryos than can responsibly be transferred at one time. This allows a couple not only to select the most promising embryos for transfer, but also to have backup embryos should the first attempts at implantation fail. The dark side-effect of this common practice is an enormous surplus of unused embryos — estimates range from half a million to as high as four million in the U.S. alone — frozen and waiting for a chance to grow and be born.

For many of these tiny children, that chance never comes. They are destroyed, donated to scientific research (that is: destroyed) or kept on ice in near-perpetuity while those responsible wait to decide what to do with them.

Her future uncertain, Hannah’s state of frozen limbo might have continued indefinitely had a pair of unlikely heroes not come to her rescue.

The pioneers next door

John and Marlene Strege didn’t set out to become groundbreaking pioneers. They simply wanted to welcome a child into their family.

Infertility issues, however, left them with few options — none of which was especially appealing to them. Doctors recommended IVF with donated eggs, but the Streges (longtime members at Zion Lutheran in Fallbrook, Calif.) were deeply uncomfortable with the idea of using the eggs of another woman, thus conceiving a child outside of their marriage bond.

They also worried about what would happen to any unused embryos.

“John and I both grew up in LCMS schools and churches,” said Marlene Strege. “So we always knew that life began at fertilization and that God is the Creator of all life — not doctors.”

“These embryos truly are ‘the least of these,’” she said, referring to Jesus’ words in Matthew 25, “as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.”

It was this concern that led them to ask about a previously unheard-of possibility: embryo adoption.

Seeking guidance

“What would God think about embryo adoption?”

This was the burning question that John and Marlene wanted answered before they were willing to consider moving forward with the pioneering procedure. Indeed, it’s a question that continues to trouble the minds of many life-loving Lutherans to this day.

Seeking answers, Marlene decided to reach out to four people she thought might be able to help: the Rev. Dr. Charles Manske, founding president of Christ College, Irvine, now Concordia University, Irvine; the Rev. Dr. Samuel Nafzger, then head of the LCMS Commission on Theology and Church Relations (CTCR); the Rev. Robert Dargatz, then assistant professor of Religion at Christ College and a member of the CTCR; and Dr. James Dobson, then head of the evangelical media ministry Focus on the Family.

“All four agreed,” recalled Marlene, “that if the original family was not going to go back and get the embryos, they needed to be adopted.”

Their response mirrored the official finding of the CTCR, expressed in its 2005 document “Christian Faith and Human Beginnings: Christian Care and Pre-Implantation Human Life”:

We consider that respect for human life can also be expressed by making embryos available for adoption by couples willing to provide the opportunity for life.

Adoption, not donation

Bolstered by the assurance that this course of action would be God-pleasing, the Streges began to explore embryo adoption seriously.

The “embryo” part was easy. Their fertility doctor had access to any number of frozen embryos they could request. It was the “adoption” part that turned out to be much trickier.

At the time, embryos were (and in most states, still are) legally considered property, not persons. As such, they could easily and simply be donated — but adopted? In 1997, the necessary regulations and procedures simply didn’t exist.

The Streges were clear, though: They wanted to pursue an open adoption, whatever it took.

“These are human lives,” said Marlene in a 2017 interview on WCAT radio, “and this really is in the best interest of the child.”

Guided by a friend at Nightlight Christian Adoptions, the Streges began to navigate California’s complex web of adoption requirements. They tackled mountains of paperwork, submitted to home studies and visits with social workers, and identified a family — Hannah’s — that was willing to place their embryos in an open adoption. Along the way, the Streges lost both their infertility doctor and their health insurance coverage for the procedure, paying for their adoption and medical expenses out-of-pocket with a providential windfall that arrived when John (a sports writer) sold a biography of then-up-and-comer Tiger Woods.

And baby makes three

At long last, in the spring of 1998, the Streges’ adoption was finalized, and 20 frozen embryonic children were Fed-Exed to John and Marlene in Pasadena.

At the time of her adoption, Hannah Strege

was visible only under a microscope

Then came the hard part. The scary, heartbreaking part.

Twelve embryos were thawed in succession. Only three survived the thawing process, and although all three were introduced to Marlene’s womb, not one of them successfully implanted.

Their nerves raw, John and Marlene waited anxiously as the remaining eight embryos were carefully thawed out on Good Friday. Again, only three survived, but of these three, two appeared to be fully viable. They were transferred to Marlene on Holy Saturday.

After one more anxious wait, the Streges finally had the good news for which they’d been waiting and hoping for more than a year.

“The doctor’s mouth just dropped when he saw the ultrasound,” said Marlene. “He determined that there was one baby, with one heartbeat, and he called it “a textbook implantation”.

“It was total excitement to find that I was pregnant.”

Hannah — her adoptive parents’ “gift from God” — was born December 31, 1998, the first-ever child to be born through embryo adoption. Her parents and Nightlight Christian Adoptions dubbed her a “snowflake baby,” reflecting her origins as a tiny, frozen, yet utterly unique human being.

The Rev. Dr. Charles Manske baptizes Hannah Strege

at the Concordia University Irvine chapel.

The toddler testifies

Not every family with small children testifies before the U.S. Congress, but that’s what John and Marlene were called upon to do in July 2001. Scientists had recently discovered how to extract stem cells from unwanted embryos (destroying the embryos in the process), and lawmakers were grappling with whether or not to allow federal funds to be used for this controversial research.

Toddler in tow, the Streges stood before Congress to testify against embryonic stem-cell research.

“At that time, they were saying that these frozen embryos have no purpose,” said Marlene. “They’re in excess of clinical need. They’re extra. They’re leftover. They’re just going to be destroyed anyway, so let’s do research on them.”

The Streges’ testimony stood in stark contrast to this point of view, highlighting the humanity and dignity of all embryonic children and the need for them to be adopted and cared for in loving homes.

“It put a face to this topic,” said Marlene.

John, Marlene and Hannah Strege

at the United States Capitol.

Five years later, in 2006, the Streges again traveled to Washington, D.C., to stand behind President George W. Bush for the first veto of his presidency. He used it to block the Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act of 2005, a bill put forward to ease restrictions on federal funding for embryonic stem cell research.

One nest empties …

Twenty years after Marlene’s long-hoped-for pregnancy, Hannah is a young woman on the threshold of adulthood, and her parents are adjusting to life in their newly empty nest.

Hannah Strege (center) and a friend pose for a

photo with Matthew Harrison while helping with

the Lutheran Hour Ministries Rose Bowl float.

“We are, all three of us, transitioning into a new season of life,” said Marlene. “We have such fond memories of Hannah’s childhood, in part because she had a wonderful Lutheran school to attend preschool to 8th and then a great Christian high school.

“However, this new season is also bringing new opportunities particularly for Hannah. It is so exciting to see the wonderful things God is doing in her life and the opportunities that are coming her way!”

… as others fill up

Across the country, other snowflake families are now following the path first blazed by the Streges. Some 1,500 snowflake adoptions have taken place over the past 20 years — over 500 of these facilitated by Nightlight Christian Adoptions, which has since become the nation’s “leader in Snowflakes® embryo adoption.”

One family following in the Streges’ footsteps is that of the Rev. Luke Timm, pastor of Living Faith Lutheran Church in Clive, Iowa. Although Timm and his wife, Joni, have three biological children, they felt a strong impulse to expand their family through adoption:

We wanted to be able to assist a mother or a family in great need, and God connected us with a couple who were faithful Christians but were unexpectedly unable to transfer their remaining embryos … [due to] a serious medical condition previously unknown. They were faced with an extremely difficult dilemma: They could not transfer the embryos to her womb, and their faith prohibited them from donating them to science or to simply allowing them to expire.

We had been praying for years — long before we ever heard of embryo adoption — that God would see fit to grace us with an opportunity just like this to ease the burden of others by way of adoption. When we read through their profile and understood their situation, we felt certain this was what God had been preparing our hearts and minds for over the years.

Doctors transferred two adopted embryos in Joni Timm’s womb, hoping that one would survive.

Both lived, and one even divided, giving the Timm family the surprise of their lives: triplets.

Three years later, the family’s joy — and their conviction that adopting embryos was a good thing to do — continues.

“Life is precious,” said the Rev. Timm, “and the Lord of Life calls us to live that proclamation with more than just our words. Embryo adoption isn’t easy, but it is a burden worth bearing.”

Timm understands that Christians may differ in their understandings of the moral and ethical implications of IVF, but he believes that when it comes to embryo adoption, common ground is easier to find:

Children who are the result of IVF — even while still frozen — are loved by God and precious in His sight.

Rachel Bomberger is managing editor for The Lutheran Witness.

This article is an expanded version of the article “Love for the Least of These,” which originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of The Lutheran Witness magazine.

If you enjoyed this article, we invite you to browse some our other life-affirming articles, read up on CTCR reports related to this topic or visit the LCMS’s Eyes of Life campaign website and Life Ministry resource page.

Life-affirming articles from LW

- “Caring, not killing, in a throwaway society” by Thomas Eggebrecht

- “Are the unborn human?” by Jason Braaten

- “Our time has come” by Peter Scaer

This is a wonderful article. We also have three beautiful children we adopted through the Snowflake program and were in a Chicago Tribune article on Mother’s Day a couple years ago. So happy to get the word out about the many precious embryos waiting for their chance at life.