Artwork and visual symbolism seen in a church building often make a confession long before parishioners hear what is confessed in the liturgy. Some of the symbolic meaning, however, may be lost to us. This is the fifth of nine articles devoted to those images which we often see — but may not always understand — in the sanctuary.

Stars have a long and distinguished history in church art, and this didn’t start with the old “stars and stripes.” In fact, once upon a time, Lutheran churches in the U.S. did not allow flags. The people understood that the secular state had no place near the divine altar.

And then a war marched in.

German roots and American stars

Many early Lutheran churches in the U.S. held fast to their European roots, and they commonly held services in German. In some remote areas, such as the hinterlands of Ontario, Canada, where I visited relatives when I was a child, German services were still listed on church signs as late as the 1960s.

Most Lutherans, however, know when to sit out a dance, and they considered it prudent to discontinue speaking German when the “Hun” lifted his ugly head during the Great War. Adolf Hitler and World War II put the final nails in the coffin of German-speaking American Lutheranism.

These events also brought out the patriotic side of Lutherans in America. To show their true colors, Lutheran congregations brought overt displays of patriotism into church sanctuaries, including the American flag. The stars and stripes have since resisted attempts to rid them from the sanctuary. Many Lutherans now view removing the flag as “un-American.”

Christian stars

The stars that spangle the U.S. flag, however, are a far cry from other stars that appear in Christian art and symbolism. While the Lutheran pastor and artist F.R. Webber mentions the five-pointed star in his book Church Symbolism and discusses its use as a symbol for the Epiphany, this is no longer the rule. More often, a star of a different form is used. Typically, an Epiphany star has a longer bottom ray, though one must hope this form was not inspired by the lyrical phrase “with a tail as big as a kite.”

With such a “tail,” it is impossible to use a five-pointed star for Epiphany unless the star is inverted, a bad idea that brings to mind all manner of ill-advised symbols, including those of Masonic and Wiccan origin.

Two versions of six-pointed stars exist in Christian symbolism, but each must be used in proper context. The Star of David, composed of two intertwined triangles, generally refers to the children of Israel and, in particular, David. The Creator’s Star, a simpler six-pointed star, often appears in depictions of the Creation.

Seven- and nine-pointed stars are a rarity, but usually represent the seven gifts of the Spirit (Isaiah 11:2–3) or the nine fruits of the Spirit (Gal. 5:22–23), respectively. Like the Star of David, they are composed of interwoven shapes, but, unlike the Star of David, a letter is often depicted on each point. Each letter corresponds to the first character of the Latin word denoting the particular gift or fruit. Of course, one must take care in the use of seven-pointed stars as they are often used in astrology, and the Baha’i religion uses a nine-pointed version.

Eight-pointed stars have a strong connection with regeneration or resurrection because the Lord arose on the “eighth day.” Eight-sided stars also allow for a long “tail,” which then gives the impression of a hidden cross. The added points issuing from between this cross give a nod to another associated symbol, the Resurrection Cross, in which rays of light burst out from behind the shape of the cross. Hence, the eight-pointed star can simultaneously symbolize Jesus’ birth, death and resurrection.

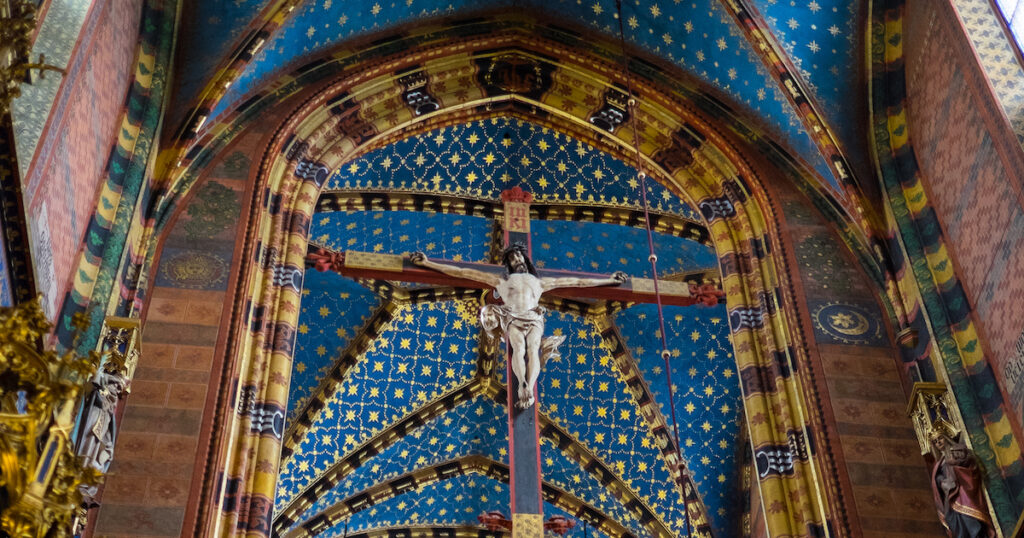

There are yet other stars. Sometimes stars in the sanctuary become as countless as, well, the stars. Ceilings in the chancel and nave are often painted blue and adorned with stars. Sometimes they occur in tight patterns similar to polka dots. At other times, they are more embellished. They may even mimic familiar constellations. However, they are not painted on ceilings to make the congregation think they are worshiping under the stars or to give the impression that the church is some kind of astronomical observatory. Rather, they serve as symbolic depictions of the angels of heaven. Their presence reminds us of where we are and what happens in the space: The Lord of all creation descends to us in the Divine Service, while we join the angels, archangels and the entire host of heaven in the adoration of Him who comes to us in His flesh and blood.

It is these stars that we ought — even as Americans — to emphasize.

Figure 1: David Staedtler CC BY-SA 2.0. Access here.

Edward,

How do we disconnect the (double triangle you mentioned) 6 pointed star from the intertestamental religion of Judaism, and use it as a Christian symbol? I’ve always seen it as a Jewish (Judaism) symbol, NOT a Hebrew/Israelite (Yahwism) symbol.

Beautiful crucifix. The blue background is striking! We visited this church when we served on behalf of the LCMS doing English Bible Camps in Poland in 2010 and 2011.

Really a beautiful article that helps us understand in depth the artwork in our churches. I’m reminded to not put faith in nations but in the Creator of the stars.