Artwork and visual symbolism seen in a church building often make a confession long before parishioners hear what is confessed in the liturgy. Some of the symbolic meaning, however, may be lost to us. This is the seventh of nine articles devoted to those images which we often see — but may not always understand — in the sanctuary.

Christians sometimes have an unsettling desire to see the face of Christ, and Lutherans are no exception. Some scholars attempt to use anthropology, ethnology and DNA to “recreate” the face of Jesus. Others run to Scripture. Still others look to the Shroud of Turin. Despite our best efforts and personal hypotheses, we are usually left sorely disappointed and soundly declare, “That’s not what He looked like.”

The Shroud of Turin is one of the few physical artifacts people have associated with the image of Christ. The photo-negative quality of the ghostly image haunts us as we consider its authenticity. And the modern-day obsession with the shroud is not a new phenomenon. Giovanni Battista della Rovere included the shroud in a painting of the Passion done during the 1500s. Other artists have done the same.

Even Eastern Orthodoxy pays homage to the image of Christ in similar fashion with its icon of the Holy Mandylion, the napkin purportedly used as a face covering for the dead Christ. The icon is a stylized image of the face of Christ.

Modern techniques have created facial models of Jesus by using combinations of the shroud, anthropological probability, digital wizardry and a hefty amount of guesswork. Many artists have simply resorted to creating likenesses based on personal preferences and cultural ideals instead. These cultural ideals can go in some strange places, though. We are all familiar with the now-faded depictions once found in every church basement — the ones that made Jesus look like any normal Swede living in first-century Jerusalem.

Orthodoxy follows a slightly more rigid set of criteria in depicting the idealized face of Christ. His hair is straight and parted in the middle. It is shoulder length, but often looks a bit wet as it hugs the form of the Savior’s head. His beard is always cleft and His expression calm.

Idealized images

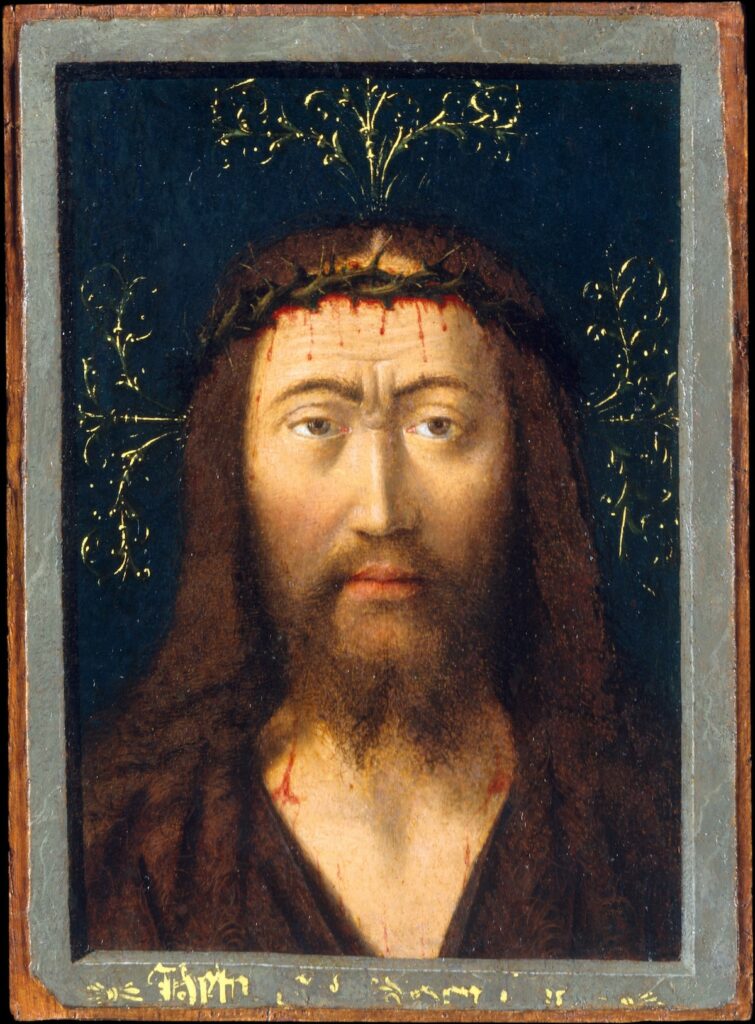

What often sets the face of Christ apart in sacred art is the idealized way in which it is portrayed. He does not look convincingly real, but somehow that makes better sense. Petrus Christus’ copy of a now-lost original by Jan van Eyck shows such an idealized Christ. The image, created circa 1445, was meant to adorn a private altarpiece. Its anatomical proportions are suspicious, but the Savior’s face is pleasant enough to regard with devotion.

Hieronymus Bosch takes the idea a step further with “Christ Carrying the Cross.” Painted 1510–1535, Bosch idealized the face of Christ while stylizing the ugliness of everyone else in the composition. It is ghastly, but the artist captured the likeness of the old Adam of everyone in that painting; perhaps as viewers we can see our own likeness there as well.

Caravaggio’s approach to Christian art goes in the opposite direction. While a brilliant painter, Caravaggio polarized art patrons of the era by painting from life instead of using idealized likenesses. We may praise his near-photographic art centuries before the modern camera was invented, but many thought his likenesses of real people were vulgar, and he was frequently plagued by requests to alter his work. “The Entombment of Christ,” painted in the early 1600s, is one of his most famous pieces and is a good example of what happens when idealism is put aside for realism. The viewer may feel as if he’s seen Jesus somewhere before — perhaps on a street or at the butcher shop. In fact, Caravaggio painted every figure in the painting with such realism that we can clearly see their imperfections and feel the pain of their lives. The pose of Christ and His gaping mouth are a bit too real as well, and the viewer is torn between devotion and revulsion.

Picturing two natures

One would think that simply depicting Christ Jesus, whether real or ideal, might be the end of things, but it isn’t. One familiar formula in Orthodox iconography attempts to simultaneously show the two natures of Christ: Consider the icon of the hypostatic union.

Icons, by their very nature, look a bit odd. The perspective and style are taken directly from an antiquated artistic period, and subsequent artists do not update the perspective and outmoded methods of modeling the human form. It’s a bit like putting an Amish girl on an haute couture fashion runway. The icons of the hypostatic union seem especially odd.

To see the effect fully, cover one side of Christ’s face and then the other. The artist mashes together two very different facial expressions in an odd-looking visage. One side of the face is that of a perfect God, while the other bears the marks of human weakness. It’s an attempt to portray the nature of the perfect God united to the weak human nature. The overall effect, however, is that of a confused Jesus, and the whole thing falls miserably flat unless the viewer knows the artist’s intent.

Artists will always attempt to depict our Savior, but it is a tall order to convey on canvas or in marble the face of Him who cannot be contained. The Old Testament teaches that no one can see God’s face and live. And yet, in Christ, God became man, and in Him, we do see God and live. We do not seek to create an image of Jesus that simply confirms our thoughts about Him. Instead, we join the Greeks who pleaded with Philip, “Sir, we wish to see Jesus” (John 12:21). And in hearing His Word, we see Him (John 1:18).

Isaiah 53 tells us a lot about how He looked. Don’t think any depictions we’ve seen come close.