by Matthew C. Harrison

Luther’s Reformation insights did not come in one fell swoop on October 31, 1517. Far from it. He’d been lecturing on the Bible at the University of Wittenberg for several years, teaching courses on Romans and the Psalms. He’d come to a clear conviction that humility was key to the Christian life — that is, the recognition of one’s sinfulness in the sight of a holy God. Already in 1516 he could write to a struggling friend, “Christ dwells only in sinners.” But this line of thought had already existed in medieval theology.

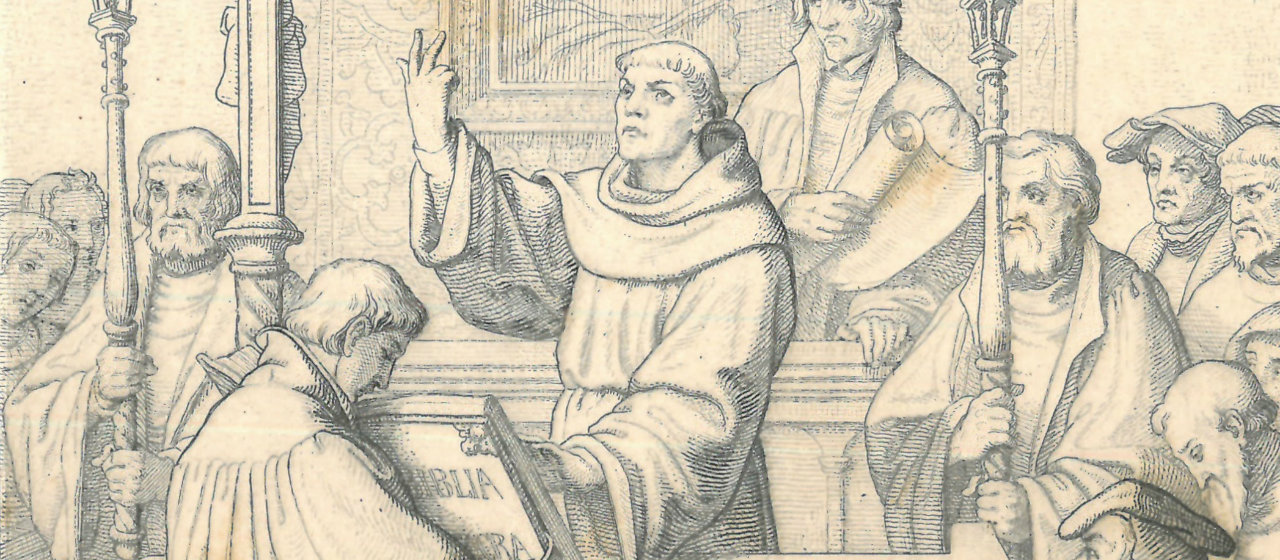

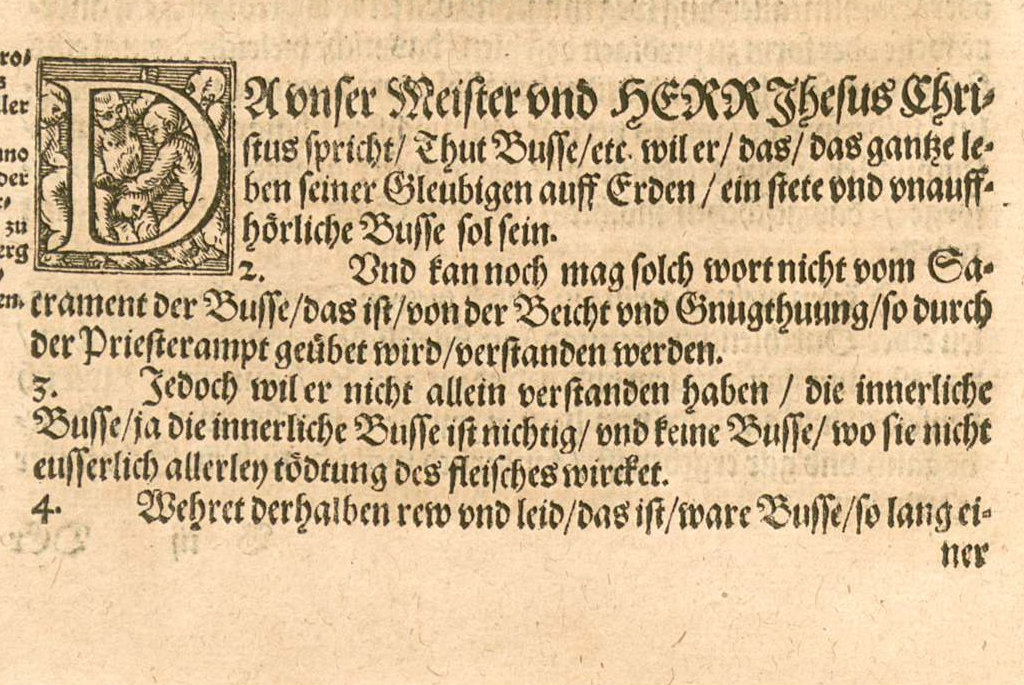

The indulgence controversy pushed him forward and into Scripture. Theses 1 of the 95 Theses states, “When our Lord and master Jesus Christ says, ‘Repent,’ he wills that the entire life of the Christian be one of repentance.” Luther had come to see that “repentance” and the Roman Catholic practice of “penance” to pay for the alleged temporal punishments for sin were not one and the same. The Roman Church had taught that purgatory had to be suffered for thousands of years to pay off temporal punishments for sins. Indulgences were dreamed up to shorten the time in purgatory. Indulgences could be had by viewing relics of this or that saint. (The Wittenberg Castle Church was full of them.) Or they could be obtained by paying cold, hard cash.

This caused Luther to blow his pastoral stack, as it were. Even at this early point, it bothered him to no end to have people claiming to be Christians and then living like swine without consequence because they had a piece of paper with a papal seal granting full remission of all sins — past, present and future. These papers would get a person into heaven “even if he’d violated the very Mother of God,” Tetzel the indulgence pusher preached!

Luther hit the church where it lived. He threatened its finances. The indulgences were being sold to finance a Prussian royal family’s acquisition of an episcopal seat. Albrecht of Mainz became Cardinal Bishop by paying the pope a large sum for that seat. To do that, he had to borrow millions from the Fuggers in Augsburg. Albrecht then hired Johann Tetzel as the fund developer to raise money to pay back the loan. Pope Leo X (whom a famous Roman Catholic historian once described as having not the slightest pastoral interest in his entire being) was happy to receive those payments so he could continue construction of St. Peter’s in Rome, including expensive artists like Michaelangelo, et al.

The authorities came down on this little monk in obscure Wittenberg. Luther was driven further into the Scriptures. In the months after posting his Theses, he was lecturing on the Letter to the Hebrews. He came to see the nature and significance of Christ’s once-for-all sacrifice on the cross. He lectured also on Paul’s Letter to the Galatians.

Luther scholar Martin Brecht suggests that Luther’s reformatory breakthrough occurred sometime after the nailing of his 95 Theses. By February 1518, Luther was convinced that true Christian righteousness meant that the Christian despaired of his own righteousness. Then, in a sermon on Philippians 2:5ff. on March 28, 1518 (Palm Sunday), Luther preached on “two kinds of righteousness.” Here Luther fully describes the Christian’s righteousness as Christ’s righteousness. The Christian’s relationship to Christ is like a marriage. Christ gets my sin, death, hell, punishment, etc. I get Christ’s birth, life, sinlessness, suffering, death, resurrection and eternal life! Luther called it the “happy exchange.”

And happy it is, indeed! “He who knew no sin became sin for us, that we may become the righteousness of God” (2 COR. 5:21). Simple as that. Profound. But muddled in the church for a thousand years before Luther. And it’s still muddled today.

This doctrine of the justification of the sinner before God for Christ’s sake, by grace, received by faith alone, is the gift given to Luther for the whole church. And it remains the gift and task of the Lutheran Church today to teach and preach it far and wide. We shall do so until our last breath, for the salvation of souls. God grant it.

— Pastor Harrison

The Rev. Dr. Matthew C. Harrison is president of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod

[box type=”note” border=”full” icon=”none”] [icon name=”check-square-o” class=””] Subscribe to the Lutheran Witness. Print and digital subscriptions are available through Concordia Publishing House. [icon name=”caret-right” class=””] Subscribe Now [/box]

THANKS PEOPLE OF GOD INDEED THIS IS SO EDIFYING SUCH THAT SALVATION COMES FROM GOD AND ONLY IN HIM WE ARE SAVED..