This sermon by the Rev. Jeffery Hemmer was originally published in Concordia Pulpit Resources © 2020 Concordia Publishing House, cph.org. Used by permission.

Text: Matthew 10:34–42

St. Robert Barnes (July 30): Who gives much thought before answering, “I do, by the grace of God” to those questions during the Confirmation Rite? But they are weighty questions. In the Rite of Confirmation in our hymnal, after the questions of one’s belief that the prophetic and apostolic Scriptures are the inspired and true Word of God, questions about one’s belief that the confession of the Lutheran Christian faith contained in the Small Catechism is faithful and true, there are three so-called vows. All of these questions and vows are weighty and not to be treated lightly. But two stand out as awfully odd questions to be asking those passing from puberty into adolescence.

“Do you intend to live according to the Word of God, and in faith, word, and deed to remain true to God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, even to death?” And “Do you intend to continue steadfast in this confession and Church and to suffer all, even death, rather than fall away from it?” (LSB, p. 273). Even to death. Suffer all, even death. Those are not unlike the “until death parts us” of wedding vows. Come hell or high water, the confirmand says, I will suffer all of it. And you will have to pry this catechism from my cold, dead hands.

But how many fall away for far more ignoble reasons than one’s own funeral? If the Roman Catholic girls are cuter, or the bowling team schedules lanes on Sunday mornings, or the music is better at the nondenominational megaplex, or the boss pays double for Sunday shifts, or the Baptists make a more compelling argument that Baptism doesn’t save than St. Peter does that it does save, or the sermons are boring, or the pastor’s a jerk, or the people are unfriendly, or the service is too long, or the babies are too noisy, or the coffee is too weak, or the hymnals are too burgundy . . . Are you willing to suffer any of those things and much more to keep the confirmation vow you made?

Who Is Willing to Suffer Even Death

Rather Than Fall Away

from This Lutheran Confession of the Faith?

I.

Answer: Robert Barnes. Never heard of him, you say? Here’s what Luther had to say of him:

This Dr. Robert Barnes we certainly knew, and it is a particular joy for me to hear that our good, pious dinner guest and houseguest has been so graciously called by God to pour out his blood and to become a holy martyr for the sake of His dear Son. Thanks, praise, and glory be to the Father of our dear Lord Jesus Christ, who again, as at the beginning, has granted us to see the time in which His Christians, before our eyes and from our eyes and from beside us, are carried off to become martyrs (that is, carried off to heaven) and become saints.

Now, since this holy martyr, St. Robert Barnes, heard at the time that his King Henry VIII of England was opposed to the pope, he came back to England with the hope of planting the Gospel in his homeland and finally brought it about that it began. To cut a long story short, Henry of England was pleased with him, as is his way, until he sent him to us at Wittenberg in the marriage matter.[1]

Barnes was an early disciple of Luther and the first English-speaking Lutheran. An Augustinian monk like Luther, a scholar and an avid reader, he was introduced to some of Luther’s writings at a regular gathering of like-minded theologians at the White Horse Inn in Cambridge. After he preached some sermons calling for reform of clerical abuses and the ostentatious way of life of the bishops, church authorities placed Barnes under house arrest for two years. When he was released, fearing for his life, he fled to Germany around 1530, arriving in Wittenberg and becoming a student of Luther’s. After studying under the Lutherans for a year, Barnes returned to England to convince his king of the scriptural truth of the doctrine of justification by grace alone.

Henry VIII was seeking an annulment of his marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and, having his petition rejected by the pope, he was courting the favor of the Lutheran princes in Germany to support his claim to authority over the church. Though Henry separated the Church of England from the Church of Rome, the doctrine remained unchanged; he only replaced the pope with the king. So Barnes’s persistent preaching and teaching against good works being any cause for salvation found him in Henry’s crosshairs. When asked to recant preaching Christ’s work as the only source for merit, Barnes rightly and courageously refused. On July 30, 1540, Barnes and two others were martyred by being bound to a stake on top of a pile of kindling and wood and burned alive. Suffer all, even death, rather than fall away from it. So he did.

II.

I doubt Robert Barnes ever took confirmation vows. Customs were different then. But he was faced with a choice few of us ever will be: Lutheranism or death, the Gospel or the gallows, the faith or the fire. And so he gives an example of what those words you may have thoughtlessly assented to look like in action. Nothing was more important to Robert than the confidence that comes from the pure, unadulterated Lutheran confession of the Gospel. He would rather risk his own life than compromise even one syllable of the Gospel. He was willing to endure anything, loss of freedom or reputation, loss of his occupation or property, even loss of life. Even death.

Jesus warned, “Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. And whoever does not take his cross and follow me is not worthy of me. Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Mt 10:37–39). You may love nothing more than Jesus. There is nothing that is more worthy of your time and devotion than hearing his Word and receiving his Sacraments. There is nothing more important in your schedule than being where Jesus gathers his elect together around altar, pulpit, and font to deliver himself to them. There is nothing you may love more than Jesus, or else you are not worthy of him.

And there’s the problem. Who does this? Who is willing to sacrifice everything, take up the cross, and follow Jesus? Who is worthy of Jesus? No one. Not even Robert Barnes whom we honor today. None of the martyrs was worthy of him. And that’s the point. You can’t come to Jesus. You are not worthy. But three times Jesus uses a form of this phrase in these short few verses of our Gospel: “I have come.” Not, “You come to me,” but “I have come,” Jesus says. To bring a sword. To set man against father, daughter against mother, daughter-in-law against mother-in-law. And yet, Jesus has come, with no questions of worthiness as the basis for his incarnation. Just a chapter earlier in St. Matthew’s account of the Gospel, he said, “I came.” He says, “I came not to call the righteous, but sinners” (Mt 9:13).

If you want to be in the same Church as Robert Barnes, which is not Martin Luther’s Church but the Lord’s Church, you’ve got to be a sinner. You cannot be worthy. You must be unworthy. You must despair of your ability to merit what Jesus comes to deliver. This is what Robert Barnes fought and died to be able to believe and to proclaim. This is what you stand with a white-knuckled grip on your hymnal and say you would rather die than stop believing: you cannot be worthy.

III.

But Jesus calls the unworthy. In this Church, there is only grace, not worthiness; only mercy, not merit; only forgiveness, not fairness.

Luther continued of his student and friend, saying, “Let us praise and thank God! This is a blessed time for the elect saints of Christ and an unfortunate, grievous time for the devil, for blasphemers, and enemies, and it is going to get even worse. Amen.”5

Jesus promises, “Whoever finds his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Mt 10:39). This is the opposite of common sense. If you find your life in yourself, you are as good as dead. And someday, you will be. And eternally, you will be. But whoever loses his life, finds it in Jesus’ death, both now and eternally. The more you strive to live, the more you die. The more you open yourself to death, the more you live.

Why would a man with a comfortable job and a favored place in the kingdom risk all of it? Because St. Robert found his life not in any of this. He found his life in the death on the cross of his Savior, whose mercy is freely given, without any merit or worthiness in those to whom he gives it. Why would anyone care one whit about this Lutheran confession of the faith that Robert Barnes died to proclaim? So that you might have life. The beating heart of the Scriptures, and therefore the beating heart of the Lutheran confession of the faith, is that life depends on Jesus, not on you. Lose your life, your confidence, yourself, and you will have all of that in him. He neither needs nor desires your worthiness. Sleep easy at night, without fear of any earthly threats or eternal dangers. You are his and he is yours. And it all depends—100 percent of it—on his work alone.

That, dear friends, is that faith from which you vow to endure anything rather than depart. Even death. Because that, dear friends, is pure and perfect faith in Jesus. It’s what Robert Barnes died to confess. It’s why he went willingly to the flame—not because of Robert Barnes, but because of Robert Barnes’s Lord. And yours. And his death. Robert Barnes died to confess Jesus’ pure and complete sufficiency to save sinners, among whom Barnes knew himself to be.

Lose your life to find it. Endure all things, even death, rather than fall away from this Jesus. Let Robert Barnes’s example encourage you. Amen.

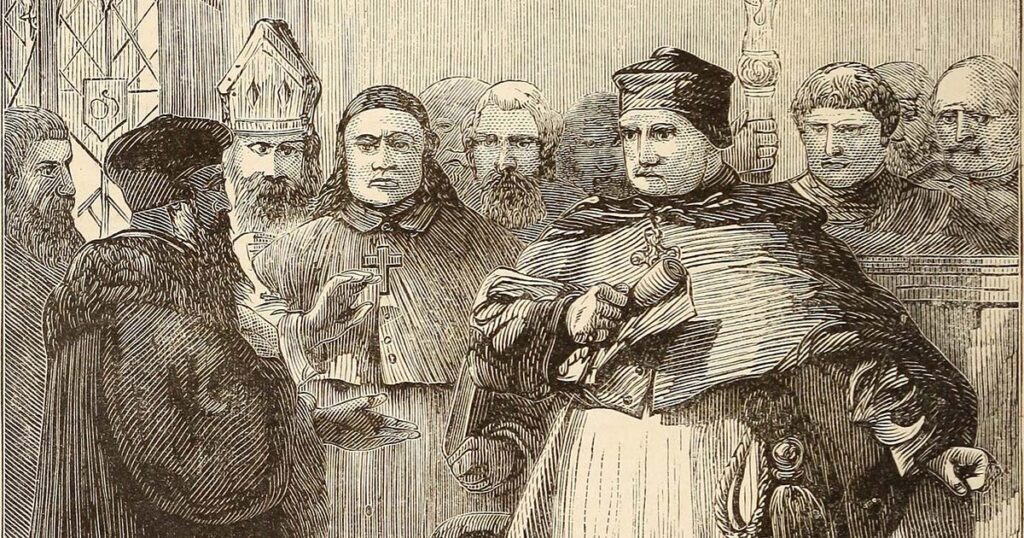

Photo: Public domain. DR. BARNES BEFORE CARDINAL WOLSEY. HISTORY OF THE REFORMATION. 709 BOOK XIX. THE ENGLISH NEW TESTAMENT AND THE CHURCH OF ROME. https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14763424424/

[1] Treasury of Daily Prayer (St. Louis: CPH, 2008), 574–75.

You reduce the author to a defense of the Lutheran Confession, when in truth he is asserting these Confessions only point us to Christ. It is Christ we die for, not our doctrine.

I recall, about a week or so before I was confirmed, approaching my parents about [reading] in our confirmation preparation [where] it stated that I would be declaring that I was being confirmed under my own free will. I told my parents that I didn’t have any free will about being confirmed, but was doing it because they wanted me to […].

I also didn’t know how I could say that “the doctrine of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, . . .to be the true and correct one.” I didn’t know any other doctrine.

I objected to the “even death” and “even unto death” phrases in the vow. I wasn’t sure I wanted to go that far.

My parents were not empathetic with my viewpoints and I dutifully went ahead with confirmation.

Those are the words of my mother recalling “some not so pleasant memories,” she said, from her Lutheran confirmation, which took place circa 1949. I wonder how many confirmands today face similar pressures that we never hear about. I also wonder:

Is it wise or even appropriate to bind the consciences of adult church members to a vow that they made “dutifully” as young teenagers largely because it was expected of them by the authority figures in their life at the time?

The author judges as “ignoble” a variety of reasons for departing from one’s confirmation vows before death. But among my acquaintances, some have thoughtfully and with their dignity intact joined Christian churches that are at least as emphatic as we are in affirming the authority of Scripture and salvation by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. Might we recognize evidence of saving faith elsewhere and celebrate it?