Our Journey with Alzheimer’s Disease

By Michael Kasting

Early in 2014, my wife and I sat at a clinic in Champaign, Ill. Sue’s six hours of testing were finished. The neurologist’s verdict signaled a sea change in our lives. Sue had generally done well, but the test of cognitive function, her memory in particular, led him to diagnose her with early-stage Alzheimer’s Disease.

We had lived in bright sunshine for more than 40 years — marriage, parenthood, ministry together at five congregations. Sue had filled multiple roles: church secretary, soloist, children’s choir director, school volunteer. Her energy and radiant face were my light when stress threatened to overwhelm me. Now our path had descended into a valley of shadows.

For several years Sue had difficulty recalling details. She took notes during phone calls and made extensive grocery and prayer lists. She wrote on cards, envelopes and scraps of paper, something I could not remember her doing before. Curiously, it did not register with me for what it was — her attempt to fill in the holes the disease was carving out of her memory.

The neurologist prescribed medications, but these produced no noticeable benefits. They simply made Sue exhausted and depressed. Meanwhile, her memory gradually worsened. We decided to move closer to family.

Accordingly, I retired from active ministry, and we moved near our eldest child, Melanie, and her husband, to a neighborhood in Oregon we had lived in previously for 11 years. Sue’s initial reaction to the move was stunning: “I hate this place!” Once familiar, it was now strange to her.

I took her to the DMV to get our drivers’ licenses. But what had once been easy was now daunting. For the first time, Sue failed her driver’s exam, and it devastated her. Afterward, she said something truly frightening: “I want to kill myself!” We had arrived in “the valley of the shadow of death.”

Friends counseled me to take care of myself. I began attending an Alzheimer’s support group. A facilitator helped us vent frustrations and pool coping strategies. I also recruited some women from our former church family to provide companionship for Sue and respite care for me.

Despite the abundant help, the changes in Sue overwhelmed all of us. A friend of mine whose husband had dementia recommended an adult day care. For a modest cost, I entrusted Sue to licensed caregivers there. It proved a significant aid to me, and by the second year I often took Sue there two days a week.

Each day, Sue grew anxious as shadows lengthened. She was experiencing “sundown syndrome,” a time of anxiety that increased as daylight dimmed. Sue would get her coat and say, “I need to go home.” Sometimes I wisely entered her reality and said, “Let’s go.” I’d take her for a drive, usually around the block, until we came to our own door. “Here’s our house!”

Descending further into the darkness of our valley of shadows brought increasingly bizarre behaviors into the daily routine. Out of my sight, Sue might be doing almost anything. Items in the kitchen disappeared from their normal spots and wound up in the refrigerator or in another room. I might find her in the bathroom with toothpaste on her face or earrings in her hair. If I sat at my computer writing, she would appear beside me with almost anything — maybe a photo album or bag of curlers — in her hands, holding it out for me to “do something” with it.

Because of her tendency to wander, I changed the locks on our doors. Even so, she managed to leave the house twice, each time requiring me to call the police for help.

Sometimes I was neither patient nor creative. Our increasing disorder collided with my need for control, and my emotions unraveled into anger. I would shout, as if sheer force of words could rein in the chaos. Sue asked fearfully, “Why are you saying this?” Why indeed, I wondered, feeling like a failure at this final exam of life.

Inevitably, I had to move Sue to a place with full-time care. I was concerned for her safety. Increasingly frustrated and exhausted, my anger sometimes boiled over into strong language. My loss of control frightened me! I feared not only for her safety, but for my own emotional health. The intensity of caregiving exhausted and depressed me. I felt I was becoming a monster. After an especially dreadful evening, I sat at my desk in tears. I could not continue this way. I made an appointment to see a counselor.

If I placed her in a facility, I could be a better caregiver while with her, couldn’t I? But I wondered, “Am I simply being selfish and abandoning my vow to love her ‘in sickness and in health’?” Our children felt such a placement was necessary for both of us. I was not abandoning Sue. I would continue to care, but in times of shorter duration and more intensity.

My support group referred me to All About Seniors, a free service that helps families find a “place for mom.” After an initial interview, the director looked at me with kind eyes: “I think you’re experiencing caregiver fatigue.” Someone had finally given a name to the pack I was carrying on my shoulders.

The director helped Melanie and me develop a list of possible facilities that offered good care. As we considered, my daughter also learned about “adult care homes” — often residential homes that had only three to five residents and a small, fixed staff. Relationships were their strength. It would be more like a family. The key feature to me was the personality of the caregiver. Most homes were less expensive than larger facilities, but there were few vacancies.

We waited and prayed. At last, three vacancies opened almost simultaneously. We chose one home and made the move in August 2019, more than five years after Sue’s diagnosis. She was one of five residents. The owner, a cheerful Filipino woman named Mina, impressed us with her affectionate care for Sue and her resolute Christian faith. Mina requested an initial period of two weeks with no contact from family so that she might bond with Sue. It was our longest separation in more than 50 years of marriage.

At first Sue struggled. The combined shock of a new place, new faces and a new routine can unsettle even the healthiest person, but for one with Alzheimer’s, it is a greater trial. Sue alternated between placid and angry. She restlessly tried the doors, asking, “Where did they go?” Her sleep pattern was irregular, and in the afternoon her “Sundowner’s” kicked in, resulting in combativeness and lashing out, endangering the staff. But their patient love and some new medications prevailed. Sue became more peaceful and began sleeping more regularly.

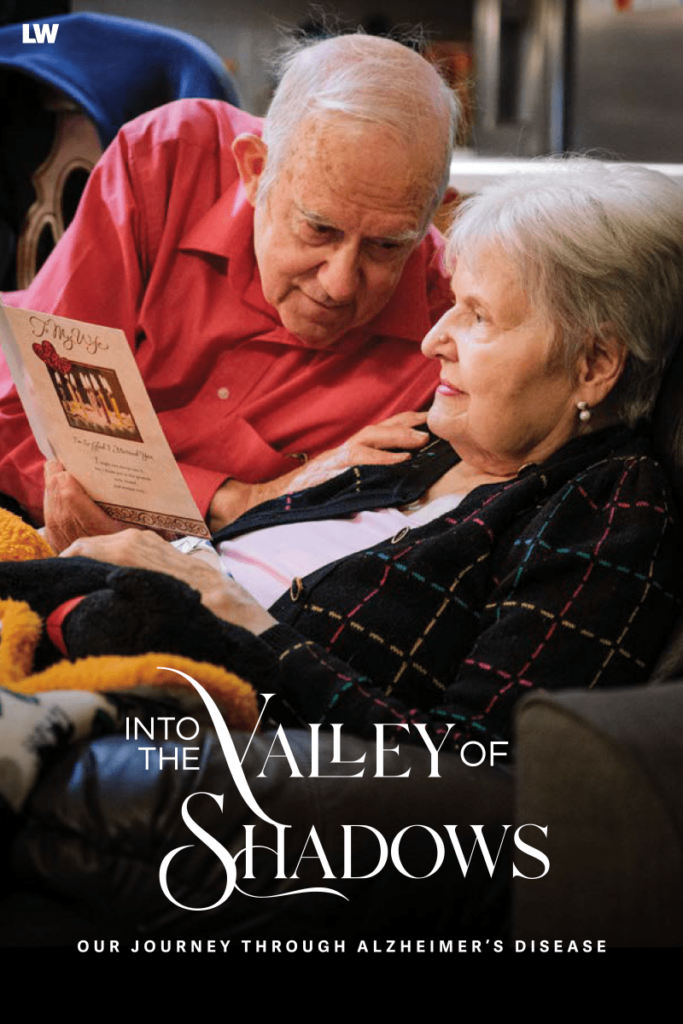

Now, three years later, that home is a peaceful refuge. During my visits, I share family pictures that elicit smiles of recognition from her. I have a grocery bag with items to kindle remembrances — a doll, a puppet, a bell she once used in children’s choir. Because Sue loves music, I sing to her the simple children’s songs she taught her children’s choirs and our familiar morning prayer, “Father, We Thank Thee for the Night.”

I still struggle with isolation and despair in this journey. I am often in tears. Our children have struggled to accept it as the new reality. We each hold a reservoir of emotions. Irrational guilt and sheer sadness mix with tender joys and moments of laughter. I am comforted that we both know Jesus as the Shepherd in this valley who restores our souls and tends us with grace.

God is also teaching me through this illness. One lesson is to see our mortality. The Benedictine monks say that one ought to hold death daily before one’s eyes to appreciate the present moment and make the most of the time God gives. I have also learned the priority of relationships over possessions. Much of my life revolved around Sue, and much of my spiritual strength depended on her example, especially my prayers.

One lesson caregivers need to learn is how to lament without complaint. The Bible not only permits us to grieve but urges us to do it. The Psalms and Lamentations model this for us. Taking our cue from these books, we lament for ourselves, and we come alongside others to “weep with those who weep” (Rom. 12:15). We lament, even as we recognize and celebrate God’s gifts.

Alzheimer’s is an (often) unpleasant journey of self-discovery, especially the discovery of one’s weakness and sin. The daily frustration of being a caregiver has shown me with painful clarity that I am not as loving and patient as I once thought. I see my desire for control. I am repeatedly summoned to a crucifixion of my selfishness that I strenuously resist. I am astonished how readily I utter vulgarities or rage at my situation. In church, I have never spoken the confession more sincerely than I do now: “I a poor, miserable sinner.” I am moved to tears at the absolution: “I forgive you all your sins.”

I hunger more than ever for the restoration God promised. New heavens and new earth. Sue in her right mind again. Heaven’s song. Seeing our Lord’s blessed face. Hearing “well done, good and faithful servant” (Matt. 25:23). In this hope I live.

Resources

This article is an abridged version of Into the Valley of Shadows, a long-form story available in a number of formats:

I am so overwhelmed by this article! I was blessed to have had Pastor and Sue Kasting’s as our pastor when I was in my late teens and early twenties. Such a beautiful family that I hold dear to my heart! I will keep them in my prayers.

Love you Kasting’s Family!

Karla, I happened to see your response to the article in LW. How sweet to read! I can still picture you and all your family, and I was likewise blessed in that friendship. I just returned from a trip to Missouri to preach at our granddaughter’s wedding. Sue would have been thrilled to see it. She is still living – now on hospice care (since February), bedfast, and unable to speak to me, but her smile is still radiant. With you we share the hope Jesus gives us all. Please greet your dad for me.

Moving and heartbreaking story. My family, like so many others, has been devastated by this disease. The experiences related by Pastor Kasting really struck a chord with me, and I very much appreciate his sharing.

Very touching article, and something we often fail to discuss. I assume it is because it is troubling to think any of us could actually lose our sense of reality in a confusing maze brought about by loss of cognitive function and memory. Those of us who are elderly think about it. We do not want our spouse or ourselves to go through this. But our Christian faith should help us to endure what we cannot control, and being assured of God’s love and His promises, this Valley cannot define us, as painful as it is for many families. Once, I had occasion to visit an elderly couple in connection with my working life. They lived in a large home, very well appointed, and in the center of their ample living room was a shiny black Grand Piano. Although the husband was not present at the time, his wife told me he was a concert pianist and had played all over the world. One year later, I returned to the home, and the first thing I noticed was that the Grand Piano was gone. So I asked the wife, “What happened to the piano?” She answered, “My husband has struggled with dementia, and he could no longer play the piano, so I had it taken out because it caused him too much anxiety.” It seems unfair that some people lose the things that gave them great satisfaction when old age and illness takes it away. Yet, as a Christian, being stripped of life’s pleasures and good health must take place as we end our journey of faith on earth, and we learn that we cannot hold onto them, but the love of God holds us still. Soli Deo Gloria.

John J. Flanagan – Songs of Faith (YouTube). 02/23/2023