“More educational spending by the (generally secular) state to teach children may teach not just math and reading but also a worldview or life orientation.” For Lutheran educators, this observation should be cause for concern. This is especially so when one considers that secular education has clearly moved away from perceiving the cosmos as the work of a governing Creator — a shift that began as early as the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 1700s and culminated in the pedagogies of 19th and 20th century theorists such as John Dewey and Jean Piaget.

Most secular education has also dismissed the role of humanity as a unique, purposeful and important part of that creation.[1] Mainstream education no longer perceives human beings as intentional agents in God’s creation, under His harmonizing authority, created with meaningful goals intimately connected to our physical, mental and spiritual nature. Instead, it reflects the secular culture which offers a scattered and incoherent vision of what it means to be human.

This secular vision offers an intensely individualized portrait of humanity, compartmentalized into many disparate components. Separated by everything from purely physical characteristics to indistinct metaphysical beliefs, people are now often seen to be entirely self-determining. This gives a new twist to the ancient aphorism of Protagoras that “man is the measure of all things.” Contemporary humanity tends to be secularly understood as self-creating, self-identifying and self-fulfilling, without a need for anything that transcends it, let alone a God who governs over it.

Secular education, suffering under a misunderstanding of the Constitutional requirement that the state must not infringe on the practice of religion, no longer has any regard for biblical teachings, such as a view of human nature in which the physical, mental and spiritual are all essential parts. Secular education would struggle to agree on an intelligible definition of human nature, or deny that such a nature even exists.

In contrast, Lutheranism is dedicated to educating in a cogent, integrated way, teaching “the whole person — body, mind and spirit.” This fulfills Christ’s injunction to us, to “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength” (Mark 12:30). It strives to do so under the auspices of God’s governance through a school ministry that “assists, equips and uplifts school educators … so that through them children may be equipped as disciples of Jesus Christ.”

It is easy to be unaware of the premises underlying educational theories and practices, the assumptions that quietly creep into our thinking and impact our actions. Understandably, as we apply ourselves to the day-to-day duties of teaching, learning and living, it can be challenging to identify where ideas and activities in opposition to our faith have stealthily saturated our pedagogy.

In 1524, Martin Luther wrote about teaching that “next to that of preaching, this is the best, greatest, and most useful office there is.” Lutherans have historically been committed to cultivating faithful learning communities, and the LCMS has built the second-largest parochial school system in the United States. Today, in the midst of a contemporary educational atmosphere which erodes the faith, we must — as did our forebears — endeavor to carefully calibrate our educational pedagogies according to Lutheran doctrine grounded in Scripture, rejecting the benchmarks and objectives of the secular educational establishment.

It would be highly beneficial in all our learning communities to clearly delineate the tenets of Lutheranism versus the assumptions of secular educational pedagogy. There are several ways in which we can accomplish this:

- Focus on God-centered, rather than self-centered, content and learning methodologies. Acknowledging our status as both saint and sinner, we should ground Lutheran education in the understanding that all knowledge begins with the fear of God (Prov. 1:7), humbly confessing our human condition of fallenness. We can then confess that truth, goodness and beauty are not found within or produced by man-made constructs, but are objective, incarnated by God, and revealed by Him. Thus, for Lutheran educators, the purpose of education ought to be the facilitation of students’ capacities to come to know God and His truth, rather than internal, subjective dictums.

- Foster vocational service in love of neighbor — rather than love of, and service to, the self. Asserting that we are saved by grace through faith and not by personal power or authenticity, Lutheran pedagogy emphasizes that in Baptism all come before God as equals, all sinful yet all saved by His work and not our own. Instead of competition and self-interest, Lutheran education forms students for vocation and service.

- Nurture faith and love of God above all else. Again, since we are saved by God’s work and not our own, the primary purpose of education must be to engender faith in our students — above worldly success or ability.

- Set students’ eyes on the coming of the new heavens and the new earth, rejecting the illusory idea that any utopia might ever be built by man here in this life.

Demographic research has shown that “exposure to LCMS primary and secondary schooling is a major factor shaping conversion: many people become LCMS due to their experiences in LCMS schools, and LCMS children enrolled in LCMS schools may have higher rates of remaining LCMS.” This confirms what we already experience, know and rejoice in: that our Lutheran schools have a deeply positive impact regarding the faith of those who attend them.

In today’s turbulent, unmoored culture, Lutherans have a profound opportunity to enrich our already fruitful schools with faith-nourishing, biblically grounded pedagogy. We can do so by unapologetically and intentionally reaffirming historic tenets of Lutheran learning community.

[1] See Thomas Korcok, Serpents in the Classroom (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2011).

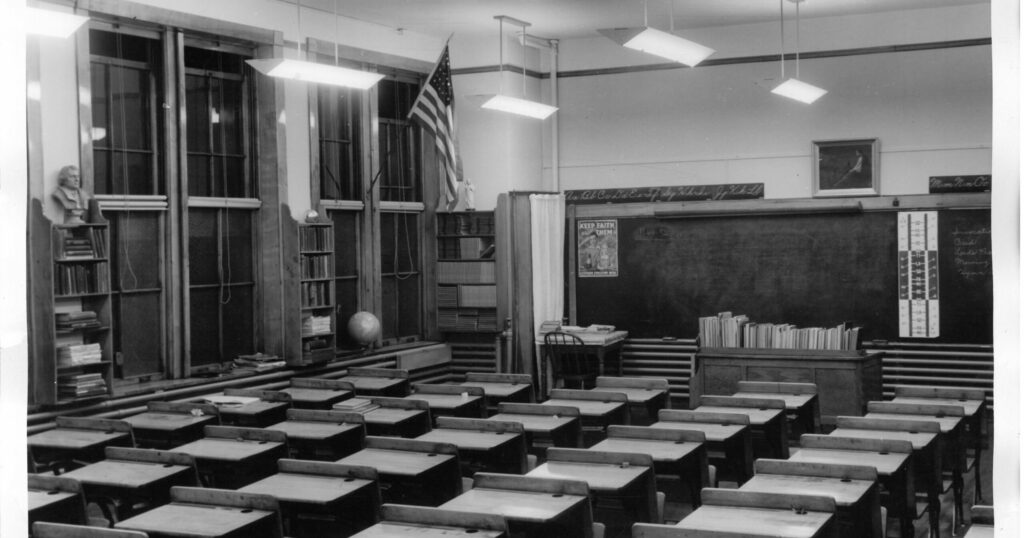

Cover image: Courtesy of Concordia Historical Institute.