An article on the issues surrounding the Walkout.

By Daniel Harmelink

“But this I confess to you, that according to the Way, … I worship the God of our fathers, believing everything laid down by the Law and written in the Prophets” (Acts 24:14).

Reducing Things

People have been reducing things for thousands of years. If you have watched a cooking show, you know that master chefs elevate their dishes by finishing off the plate with a reduction. A reduction is produced by expertly simmering a stock, sauce or fruit juice to intensify the flavor. It is a tricky process, and the simmering sauce can quickly become a burnt, sticky, good-for-nothing goo.

Gospel Reductionism boils down our understanding of Holy Scripture to the Gospel — however the “Gospel” happens to be understood. For the Gospel Reductionist, every theological point is accepted or rejected on the basis of the answer to the question, “What does this have to do with the Good News of the Gospel?” The unintended consequences are much worse than burnt tomato sauce spoiling a piece of grilled chicken.

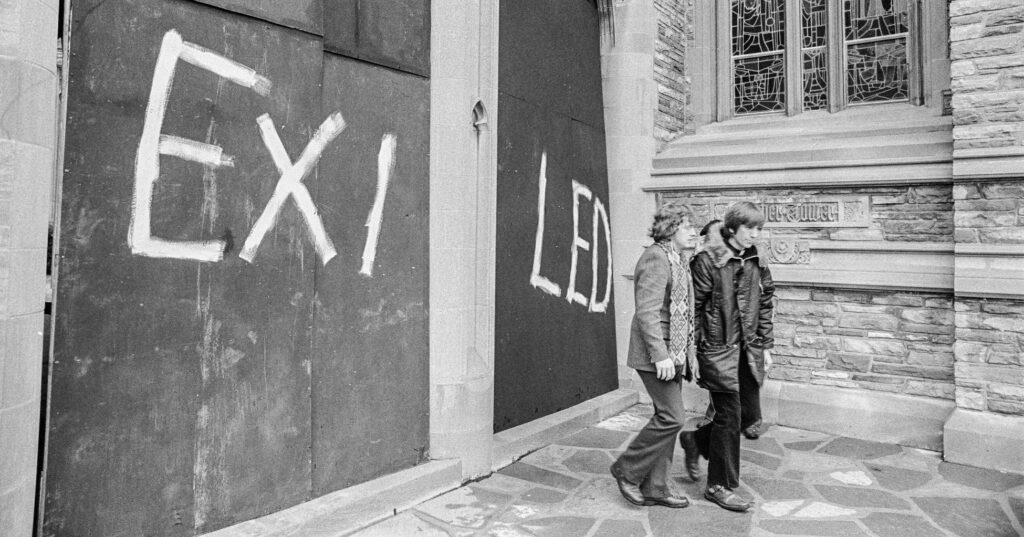

The crises of theology and practice that boiled over — or, perhaps in this case, goo-ed up — The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS) in the 1970s resulted from Gospel Reductionism. The event that immortalized this in the minds of LCMS members occurred 50 years ago on Feb. 19, 1974 — the Walkout. Faculty and students of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, walked off campus in protest of what they perceived as restrictive and backwards teaching about the Bible and God’s Word.

Scholarly Validation

The belief that the Holy Scriptures is — in all its parts — the inspired, inerrant Word of God that reveals Christ, the one object of our faith, was standard fare for millennia, until higher criticism made inroads in Western academia. Academics thought they were smarter than the “simpletons” in the pews and approached the Bible with the same skepticism and critical attitude often used to “scientifically” validate secular writings. They began by discounting any phenomenon recorded in the Bible that could not be repeated in the laboratory: angels, miracles, the virgin birth, prophecy, all the way to the immortality of the soul and the resurrection of the dead.

In the mid-1900s, LCMS seminaries and colleges decided to pursue prestige among other institutions of higher learning by securing professors with earned degrees from large, mainstream universities in North America and Europe. Graduate students from the Missouri Synod were exposed to the higher critical theologies of post-World War II Europe.

Some Missouri Synod academics concluded that the Missouri Synod needed to break out of its Midwest barrio to show the larger Lutheran community that it had substantive contributions to current theological discussions. They shelved the writings of “parochial” C.F.W. Walther for the more “relevant” writings of Swiss theologian Karl Barth; they put aside Franz Pieper’s Christian Dogmatics to pick up more contemporary theologians such as Rudolf Bultmann, Paul Tillich and Werner Elert. All these modern theologians said nice things about Luther, but they broke with him and openly expressed serious doubts about the inspiration and inerrancy of the Old and New Testament texts.

A foreign theology slowly crept into the classrooms of Missouri Synod seminaries and colleges. While it seemed that professors were distinctively Lutheran in their emphasis on Christ and the Gospel, “Christ and the Gospel” also began to be used to discount clear teachings of Scripture. “Christ and the Gospel” provided cover for a disdain, picked up from modern theology, for the laity’s “uncritical” acceptance of the entire biblical record as the inspired and inerrant Word of God that alone reveals Christ and the Gospel.

Higher critics did not understand the impossibility of maintaining faith in Christ apart from the authority of the inspired Scriptures. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, increasing numbers of those teaching in Missouri Synod classrooms of higher learning were trying to convince their students that the real understanding of the Word of God was only possible through a skillful intellectual quest to find the authentic Jesus and the authentic Word of God contained within the Bible.

The Real Issue

The discussions and debates culminating in the “Walkout” show clear evidence of “Gospelism” or “Gospel Reductionism.” Many who have written about Concordia Seminary in Exile (which became Christ Seminary— Seminex) credit the term “Gospel Reductionism” to John Warwick Montgomery and a series of lectures he presented in 1966. Montgomery’s concerns revolved around the dangerous enterprise of modern progressive theologians who had abandoned the inspiration, inerrancy and authority of Holy Scripture as held by Martin Luther and the Book of Concord.

Both J.A.O. Preus (then president of the LCMS) and John Tietjen (then president of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis) identified this new way of interpreting the Bible as the central issue behind all the other more commonly publicized issues dogging the Missouri Synod. Preus wrote in the Preface of the September 1972 Report of the Synodical President of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod:

While the issues are many and complex, the St. Louis Seminary faculty and the synodical President at a meeting on May 17, 1972, agreed that the basic issue is the relationship between the Scriptures and the Gospel. To put the matter in other words, the question is whether the Scriptures are the norm of our faith and life or whether the Gospel alone is that norm.

A few months after that May meeting, in late 1972, the majority of professors at the seminary asked the question: “Is the Gospel alone sufficient as the ground of faith and the governing principle for Lutheran theology?” They answered in the affirmative. Holding the Gospel to be the sole judge of what in the Bible has authority over the Christian, they did not appreciate Preus and company sticking their noses where they were not welcome with their out-of-step belief that Scripture judges us and not the other way around.

Torpedoing the Christian Faith

When the Holy Spirit-inspired St. Paul proclaims, “We preach Christ crucified” (1 Cor. 1:23), the apostle was not announcing that every other point of revelation in the Bible is inconsequential for Christian faith and life. The Bible is wholly inspired and inerrant, not only in theological points but in all that it says.

If the unbelieving world objects and brings up a perceived discrepancy or contradiction or error in Scripture, we stand with Christ and His clear understanding of the whole of Scripture as the clear, trustworthy, unbreakable Word of God. We cannot have it both ways. People can believe that their conviction that the Bible contains errors does not affect the authority and certainty of God’s Holy Word, but their misplaced conviction dishonors Christ, His understanding of the sure and certain Word of God, and destroys the certainty of the Christian faith and trust in the Christ of Scripture.

We might also say it this way: The Bible does not contain the Word of God; the Bible is the Word of God. And without the Word of God, we have no Christ. Full stop. That was the warning given in the late 1960s and early 1970s to professors at Missouri Synod colleges and seminaries who started walking down the hermeneutical path of higher criticism and Gospel Reductionism.

When we critique the Bible using our intellectual abilities to pick out religious truths from among factual or historical errors, we have already destroyed the integrity and authoritative position of God’s eternal revealed will for us and our yet-to-believe neighbor. This is a magisterial use of reason (putting the human mind over the Word of God) rather than a ministerial use of reason (putting the human mind underneath or in service to the Word of God). Up until the 1960s and 1970s, Lutherans recognized the value of the ministerial use of reason, and so used historical linguistics, grammar of the original languages and other God-pleasing applications of human thought to better understand Holy Scripture. They refused, however, to stand over Scripture in a posture of judgment; that is, they refused the magisterial use of reason against Scripture. Even so today, we do not subject the Bible to examination and dissection under the unbelieving world’s scalpel of critical, “scientific” investigation.

The Lutheran Confessions echo Luther’s clear stance that the magisterial use of reason ultimately destroys saving faith in Christ:

He [Luther] has clearly drawn up this distinction: God’s Word alone should be and remain the only standard and rule of doctrine, to which the writings of no man should be regarded as equal. Everything should be subjected to God’s Word.

(FC SD Summary 9)

It does not say, “Everything should be subjected to the bits of the Bible that professional academics at the seminary consider ‘Gospel.’” No, everything is subject to the authority of every teaching of Scripture.

Not Just Gospel Bits

The Gospel, as defined by the Lord’s inspired prophets and apostles, is the shining jewel of our Christian faith. Martin Luther confessed this right from the beginning of the Reformation. He writes in the 95 Theses: “The true treasure of the church is the most holy Gospel of the glory and grace of God.” Nevertheless, the Gospel is not the answer to every theological question and doctrinal position, just as “Jesus” is not the answer to every question asked during a children’s sermon.

This is especially true when it comes to discerning what is and what is not the authoritative Word of God. If perceived “Gospel-ness” is the measure of theological validity, the result will be a burnt goo of a faith that spoils everything it is drizzled over. For example, the bodily presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper is a clear and essential teaching of Christ in the New Testament. Saying that it does not really matter if you believe that we receive Christ’s body and blood in the Sacrament because it does not impinge on the Gospel — or does not affect the right understanding of the doctrine of justification — undermines the gift of God in the Sacrament. This Gospel Reductionism lessens and weakens the authority of the clear Word of God by arguing that anything is allowed if it does not touch on the Gospel.

Consider the doctrine of justification. It is the golden sun around which all other biblical doctrines orbit. By grace through faith, unworthy sinners are declared righteous on account of the sinless life and substitutionary suffering, death and resurrection of Christ. That is the intended direction and goal of everything the prophets and apostles put down in writing. But not everything in the Bible is Gospel; not everything in the Scriptures can be reduced to the doctrine of justification. There are other moving parts integral to the biblical witness, other points of doctrine inseparably linked to the Gospel that can never be surrendered.

Everything revealed in Holy Scripture is the Word of God and authoritative for Christian faith and life, even if it is not the Gospel proper. When we hear something from the Lord in Holy Scripture that is difficult to take or hard to understand, we do not dismiss it by waving the magic wand of “it has nothing to do with the Gospel.” With God-given trust in the revealed Word of God, we stand beneath Scripture. The Bible has the final say in all things it touches on — for the “Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35).

Keep Us Steadfast

May our merciful Lord have mercy on us and help us to learn from the devastating crises of our history. May He spare us from flirting with the dead-end approach of Gospel Reductionism and give us the ability to speak a simple “Amen” to the authority and integrity of the Bible and the one trustworthy Redeemer the Bible trumpets.

Digging Deeper

Schurb, Ken. Rediscovering the Issues Surrounding the 1974 Concordia Seminary Walkout. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2023.

“A Statement of Scriptural and Confessional Principles.” The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. lcms.org/ scriptural-and-confessional-principles.

Commission on Theology and Church Relations. Gospel and Scripture: The Interrelationship of the Material and Formal Principles in Lutheran Theology. St. Louis: The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, 1972.

“Brief Statement of the Doctrinal Position of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod.” The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. lcms.org/doctrinal-positions.

This article originally appeared in the February 2024 issue of The Lutheran Witness.

The thing I love most about LCMS is that the Bible says exactly what it means and is NOT subject to interpretation.