By Cameron MacKenzie

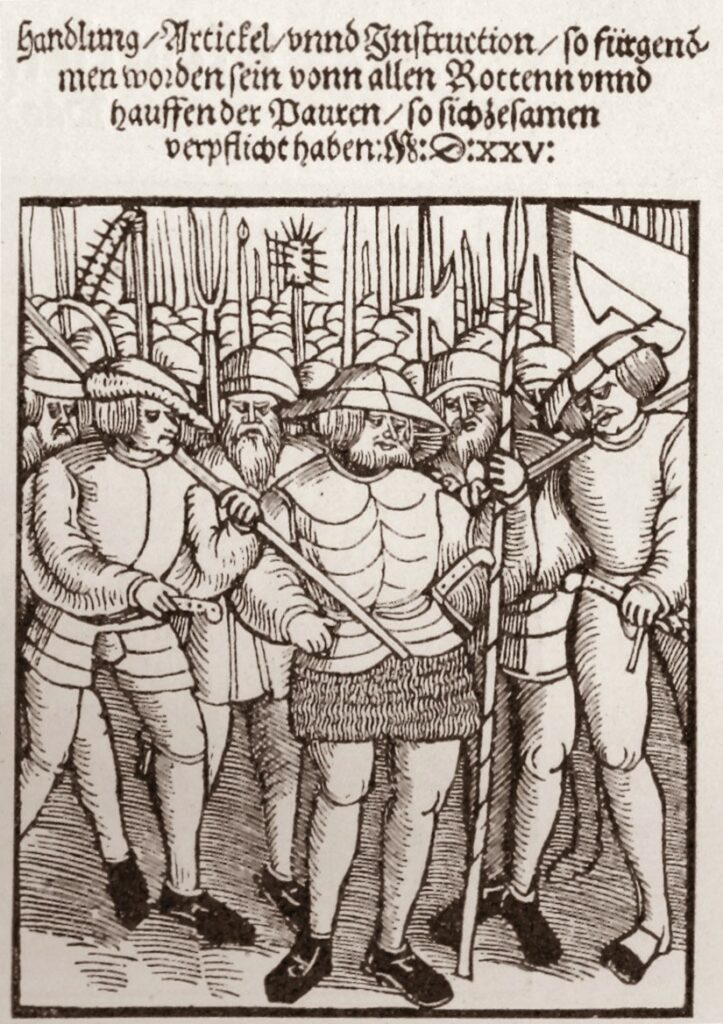

Five hundred years ago, in the mid-1520s, a series of riots and revolts now known as the “Peasants’ War” broke out in Germany. These revolts were waged by groups both small and large against the established orders of church and state. They were regional, uncoordinated and inspired by local grievances like high prices, rents and taxes. By the time they were over, half of the German lands had been torn apart and as many as 100,000 people lay dead. To Luther’s grief, these rebels used the language of the Reformation to justify their revolt. This twisting of theology to political ends — and Luther’s response to it — can serve as a lesson for us still today as we engage as Christians in the political realm.

Similar uprisings had occurred in Flanders in the 1320s, England in the 1380s and several other places in the 1400s. Though often called “peasants” revolts, participants included urban rebels and renegade nobles as well as rural peasants. But none of these earlier uprisings had occurred at such a scale, or with such a monumental death toll.

Initially, the rioters caught the authorities off guard and met with some success. But for the most part, they were badly armed and poorly trained and no match for the forces sent against them by territorial rulers who slaughtered them by the thousands. When the fighting finished and law and order were once more established, not much had changed. The status quo ante remained pretty much in place.

The German Peasants’ War occurred after the invention of the printing press and just a few years after Martin Luther began the Reformation. Tragically, the Reformation provided them with a vocabulary to justify their actions, and printing gave them the means to promote their cause widely.

Propagandists for the peasants employed Lutheran themes like “Christian liberty” to justify their actions. Some even called on Luther by name to take up their cause. Luther wrote in response to such appeals. He wanted to rescue his theology from those who were abusing it and also to address biblically the responsibilities and claims of both sides in the dispute.

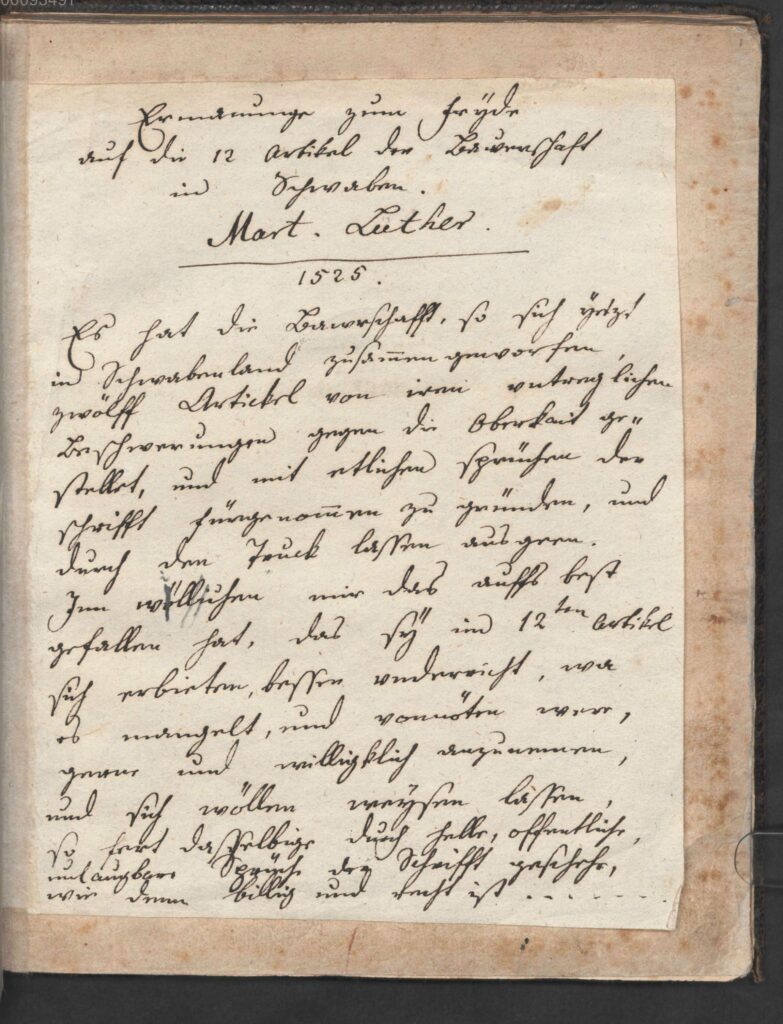

The printing press had provided Luther with a useful tool for spreading his message, and he had employed it to great effect. By the time the Peasants’ War broke out, he was a best-selling author. But others could use the same tool, and they did so, promoting the uprising with tracts and pamphlets. One such publication drew Luther’s attention: “The Twelve Articles of the Swabian Peasants.” First appearing early in 1525, it was printed and reprinted in various parts of Germany (sometimes with local variations) and became a manifesto for the revolt.

As its title suggests, the author of this tract (Simon Lotzer, a journeyman furrier and lay preacher) presented the rebels’ demands in 12 little sections. For each of these, he provided an explanation, supported by arguments from customary law and the Bible. He used the doctrines of creation and redemption to argue for social rights and economic privileges — everything from the right to hunt, fish and cut wood in community lands to the abolition of the death tax and serfdom. All this, he argued, was necessary to “live according to the Gospel.”

That’s what brought Luther into the discussion: their claim that the Gospel justified their goals and rebellion. In the 12th article, the peasants submitted the previous 11 to the judgment of God’s Word and promised to correct any demand that failed the scriptural test. For the reformer, all their demands except one — the right to call a pastor — fell short of that measure. God’s Word was not on their side, and they were misusing God’s name by claiming His support for their cause. For Luther, it was a grave sin to say, “Thus saith the Lord,” when the Lord had not spoken (Ezek. 22:28).

This has obvious relevance for us today. Christians must be careful not to “baptize” their politics, i.e., to describe their candidate, party or policies as “Christian” when they are not clearly mandated by God’s Word. It is one thing to argue, for example, on behalf of caring for the poor and needy (which is biblical), and another to say that, in the name of God, we must do so in this particular way or by electing this particular candidate. Similarly, while Christians in the United States thank God for the blessings of liberty, they cannot use the Scriptures to justify imposing their political or economic systems on other nations.

Luther published a treatise in the spring of 1525 that addressed the Twelve Articles as well as the general issues that were stirring up trouble between rulers and ruled. He hoped that a clearer recognition of the rights and wrongs of both sides might calm things down. Titled Admonition to Peace, Luther castigated the rulers for exploiting those whom God had entrusted to their care. Their main concern should have been the well-being of their people, including tending to their spiritual well-being by giving free course to the Gospel in their territories. Instead, they opposed the Reformation and abused the poor in order to live extravagantly. If their people rebelled, that’s what they deserved. God was punishing them.

However, the wickedness of the rulers did not justify rebellion by their subjects. That, too, was a violation of God’s Word. In his Admonition, Luther scolded the peasants. Not only were they misusing God’s name to promote their cause, they were also disobeying and threatening authorities that God had placed over them. Luther relied on passages like Romans 13:1–2 to justify his argument: “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore whoever resists the authorities resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgment.”

This meant that Christians then — as now — were supposed to obey the laws, pay the taxes and fulfill the obligations imposed upon them by their government regardless of whether such impositions were fair or not. Disobedience and especially rebellion were sins against God who had placed those rulers over them in the first place. God would hold them responsible for their unjust actions. That was His job, not the people’s.

In other publications, Luther set limits on the Christian’s obligation to obey. If the authorities tried to impose false beliefs and practices in religion, a Christian had to say no. Our conscience belongs to God, not the government, so “we must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). But in the Admonition, Luther’s concern was not to justify disobedience in matters of faith but to insist on obedience in matters of this life. That was the issue for the peasants.

For Luther, it was clear that the sins of each and either side could move God to intervene by bringing punishment on them in the form of violence and destruction here and hereafter in hell. Both sides needed to repent and avoid those consequences.

Whatever Luther hoped to accomplish with his Admonition, it proved too little and too late. Violence was exploding just as Luther was composing his treatise. Castles, convents and monasteries fell into the hands of the peasants. Cities like Erfurt, where Luther had gone to school, gave in to the rebels. Thuringia, Luther’s ancestral home, was greatly afflicted. He learned about what was happening from relatives and friends, as well as by traveling in affected areas himself. As he did so, he tried to preach repentance and peace to the rebels. Bearing injustice with patience was God’s will, not rebellion. His message fell on deaf ears. The rebels weren’t listening. Hecklers created a racket like ringing the bells to disrupt his sermons. They even threatened him with physical violence. Luther described one man as possessed by 100,000 devils.

So Luther wrote again, this time an appeal to the authorities to use force against the rebels whom Luther now identified as agents of Satan. Originally planned as an appendix to his Admonition, his second work, Against the Robbing and Murderous Hordes of Peasants, found a ready audience and was frequently printed on its own. In this work, Luther argued that God had established government to maintain the peace by using force against those who threatened it. This meant the peasant rebels. Rulers should not hesitate even to kill those whose actions threatened the property and lives of others. And, of course, that’s what they did. Tens of thousands were slain.

Luther received a great deal of criticism for the vehemence with which he urged his case against the rebels. He even declared that if an agent of the authorities died while using force to suppress the uprising, he might actually be a martyr. A shocking comparison! The martyrs of the Early Church were noteworthy for their nonviolence in the face of horrific persecution, not for their taking up arms to kill the wicked.

So Luther wrote a third tract, An Open Letter on the Harsh Book Against the Peasants. Although he admitted that there was a place for mercy in the treatment of some of the rebels, he did not back away from his main point. Rebellion against civil authorities was a clear violation of God’s Word that had to be suppressed and punished. Rebellion not only brought harm to the authorities but also to society in general. Everyone paid a price when law and order broke down.

Much of what Luther published over the course of his lifetime came about because of specific circumstances, and that’s certainly true of the three pieces mentioned here. Clearly, our circumstances are far different from Luther’s. Nonetheless, the biblical principles that Luther was applying to the people of his day remain valid in ours. It is by divine providence that we have the government that we have. It has been established by God and is responsible to Him for how it carries out its responsibilities. Those responsibilities revolve around the temporal well-being of the people, not the least of which is a peaceful society in which the Gospel may be preached, heard and followed. Government doesn’t preach, but it maintains the conditions under which God’s Word can be preached.

God’s people have the responsibility to obey the government that is over them, even when they don’t like it or it seems unjust — or when they lose an election. When government orders them to disobey God’s Word, they must refuse. But like Daniel in the lions’ den, their disobedience must include a willingness to suffer unjust punishment rather than rebel.

Those are the principles, and they remain in place. But there is at least one difference between us and Luther that complicates our situation and adds to our responsibilities. We are not just under the government and subject to its rules; we are also a part of the government. What Luther said to the rulers about their duty to act selflessly in the service of others applies also to us, at least as voters and even more so if we are active in politics or actually hold public office. We are responsible for enacting good public policy and for carrying it out ourselves or choosing good officials to do it for us.

In this, as in everything, we must act as Christians. At the very least, this means not lying about or defaming our political foes. It also means not voting selfishly — on the basis of what we can get out of public policy for ourselves — but rather on the basis of what is good for society as a whole and especially those among us who are least capable of helping themselves. God gives government the task of punishing evil and promoting good. Our participation in government at whatever level should aim at accomplishing God’s purposes and not our own.

Loving God means obeying the government. He has established it. Loving our neighbor means utilizing government in the interests of others and not ourselves.

This article originally appeared in the January 2025 issue of The Lutheran Witness.

Cover image: “Charge,” from German Peasants’ War series, by Käthe Kollwitz, 1903.

That’s ’bout half the story and leaves much of importance unsaid.

Here’s two words to contemplate – “Beer Wolf”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beerwolf

Point of fact, there would be no Lutherans without Gods will – manifest in armed resistance – to the Emperor and Catholic complicit princes in the 16th and 17th century.

Why was this article not posted after the 2020 election?

Rachel,

This article came from our January print issue on “God’s Two Kingdoms,” which was planned last summer and the articles for which were written before this latest election. This theme was planned around the 500th anniversary of the German Peasants’ War, which you can read about in this article, which ended 500 years ago in 1525. It is a timeless topic particularly relevant during an age of high political tension in our nation, which encourages readers that God is on His throne and rules through the current elected officials, regardless of whether we like them or not. I’d encourage you to check it out!

This should’ve been posted on Jan 1st, 2021.

Given that we won’t discipline our own for breaking election laws nor endorsement via presence…

Woe to us hypocrites.

Luther was culpable in the Peasants uprising, and worthy of criticism for his own role. It would be dishonest to make excuses for his failings, his vitriolic and harsh words, and his encouragement to the Royals to conduct a genocide against the peasants. Luther is also singularly responsible for words and writings which were anti-Semitic, cruel, and useful to those who quoted him while persecuting the Jews of Europe and ultimately found useful by Hitler and his National Socialist agenda. While it is true we are to love our leaders, as citizens do we have any obligation to resist evil? What of laws which wicked governments impose? True, we cannot be so political that we forget that Christians are to serve God’s Kingdom first, and as we cannot place our hopes in political leaders, we are still charged to refute, admonish, and resist evil in our time. I am afraid some Christians use the two kingdom rule as a means to avoid involvement in political and cultural wars, remaining silent in the face of the decay of the societies in which they live. Fear of persecution and social exile causes many to retreat into isolated enclaves. I do not believe that is the extreme Our Lord desires.