by Uwe Siemon-Netto

Back in the days when rulers wore crowns and ermine, only one man in their realm had full freedom of expression—the court jester. He could be vile. He could be insulting. He could be over the top. If the sovereign was truly a sovereign, that is to say, if he had the stature of remaining unfazed, the jester was safe. If, on the other hand, the ruler lacked self-assurance, the poor fool might find himself a head shorter.

In a democracy, the people are the sovereigns, and their jesters are shock jocks such as Don Imus. Perhaps they are not as witty as jokers of ages past—calling young black sportswomen names that shouldn’t appear in family magazines seems to suggest that. But it also appears that collectively we—today’s sovereigns—may also lack the stature of our crowned predecessors. At any rate, Imus was guillotined for using the jargon of rappers and ghetto gangsters.

My heart isn’t bleeding for Imus. His type is as alien to me as are all men dismissing women, God’s most lovable gift to us. But I pity the insecure “sovereigns” who, led by pundits such as Rev. Al Sharpton and others, waste millions of minutes of airtime bemoaning the alleged loss of their dignity. Is there nobody out there left with a sense of logic? How could one scruffy radio host’s gaffe possibly harm anyone’s self-esteem, which is a prerequisite of sovereign rule?

Let me explain why this episode has angered me so. I came to this country in 1962 as a young foreign correspondent from Germany. One of my most rewarding assignments then was covering the civil rights movement. I still have its anthem, “We Shall Overcome,” in my ears. It was stirring when blacks and whites sang it together, notably its second stanza:

We’ll walk hand in hand

We’ll walk hand in hand

We’ll walk hand in hand some day.

We were certain then that this “some day” was near. It would have seemed inconceivable then that four decades later one broadcaster’s verbal junk would so rile America’s people—the sovereign—that our substandard media pushed aside momentous international events—genocide, for example—to make room for endless drivel over three words many Americans had never heard before.

Worse still, who would have imagined back in the Sixties that the self-segregation of the races would become a major issue in the year 2007? Who would have thought that after prattling for decades of the need for multiculturalism, black students would only sit with blacks and white students with whites and Hispanic with Hispanics, as CNN personality Paula Zahn recently reported from the cafeteria of a high school in Buffalo, N.Y.?

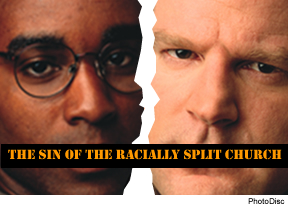

What distresses me is the church’s flaccid role in this sorry state of affairs, in helping to resolve a problem that is ripping America apart. All of us have read Gal. 3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek … for you are all one in Christ.” That does not seem to be Sharpton’s motto. He seems to never mention Christ on camera. In many ways, perhaps, he is more lobbyist than pastor.

What interests me is what we Lutherans are doing to remedy this situation. We have the perfect theology for it. We have educated and erudite black pastors and a wonderful Board for Black Ministry Services. Wouldn’t it be great if reporters sought them out for their observations? No other Christian tradition is better equipped than Lutherans to inform the nation of the unshakeable truth so dismally lacking in many TV religious pronouncements—that an ethnically split body of Christ is a theological absurdity.

I know whereof I speak. For the last six years, my wife and I have been members of Mount Olivet Church, an almost all-black LCMS parish in downtown Washington.

We joined Mount Olivet, not to make a political statement, but simply because this happened to be our neighborhood church, a confessional, liturgical, and welcoming congregation blessed with a beautiful sanctuary and a powerful Christ-centered preacher by the name of John F. Johnson.

We were warmly embraced. Not once did we sense any hostility because of our different pigmentation. We were almost immediately asked to serve on the Board of Trustees, and I on the constitution committee. When I had a heart attack, Pastor Johnson and an elder were at my bedside almost instantly. A young Jewish friend from New York happened to be in Washington at the time. So impressed was she with Rev. Johnson’s demeanor and the sincerity of his prayers that when she next visited Washington she insisted on going to church with us.

Yet Mount Olivet has remained an all-black congregation. To be sure white Lutherans drop by occasionally, but none seems to join. It is possible, of course, that our members might have been less welcoming had they suddenly been overwhelmed by a massive influx of whites. But what baffles me is why the knowledge of Gal. 3:28 has not persuaded at least some newcomers to help integrate our church family. Clearly it hasn’t dawned on us that our two-kingdoms doctrine provides us with the perfect tool to help overcome the ethnic divide.

Race relations are, of course, the property of the secular “left-hand kingdom,” as Lutherans say. They can only be governed by natural reason. The Gospel has no answer to questions such as affirmative action. Neither does the Gospel have anything to say about the proper reaction to a shock jock’s slur. All this comes under the purview of the Law.

But as the apostle Paul has taught us, pigments should be invisible in the spiritual right-hand kingdom, in divine service, in Bible class, or at the altar rail. In a real church—at least in a church affirming the true presence of Christ in the elements of the Lord’s Supper—whites and blacks kneel side by side, drinking from the same chalice, and it would be very odd if this knowledge of being one in Christ would not radiate in some way into the worldly realm where we live out our biological life with all its troubles.

This is not some lofty theory; it should be a fact of faith. Either we are hypocrites if we ignore race on Sundays in church but make it an object of distrust on Monday in the office or at the negotiating table, or we allow the knowledge of being one in Christ to affect our everyday existence.

The time has come for the Lutheran church to stop being timid. We of all Christians should know that it is the church’s role to fortify the left-hand kingdom, not by interfering with its sovereigns’ craft, but by advising them of what’s right and wrong. The alternative is the destructive power of klutzy jesters like Don Imus and pundits like Al Sharpton. We have better people to offer. Let’s hear from them.