By Dr. Erik Herrmann

For two millenia, the apostle Paul and his writings have been central to the history of the Christian faith. For Luther, the clarity of Paul’s message is of the utmost importance.

It has been 2,000 years since the birth of the apostle Paul. Actually, historians are not entirely certain when Paul (Saul) of Tarsus was born, placing his birth sometime between AD 7 and 10.

It has been 2,000 years since the birth of the apostle Paul. Actually, historians are not entirely certain when Paul (Saul) of Tarsus was born, placing his birth sometime between AD 7 and 10.

Nonetheless, despite this lack of precision, Christianity throughout the world is celebrating the life and ministry of the apostle Paul. Pope Benedict XVI announced last summer that 2008–2009 will be a special Jubilee year in honor of Paul. Protestant churches, too, are planning special events to mark the occasion. So also is Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, which is dedicating its next academic year to the theme, “A Year with Paul,” with opportunities for study and reflection on this remarkable vessel of God’s grace.

But one hardly needs to wait for an anniversary to observe the importance and impact of Paul. No other biblical author has received so much attention, so much study, so much controversy in the history of the church as this apostle and his writings.

One church historian famously described Paul as the “conscience of the church,” going so far as to say that all of the critical turning points of Christian doctrine in the history of Christianity were “Pauline reactions.” Perhaps this overstates things a bit, but it is striking nonetheless to consider how central Paul and his writings have been through the centuries.

In the second century, Marcion created no small stir when he argued that Christians should reject the Old Testament because Paul had taught that the Law did not justify. In order to write against Marcion’s dangerous ideas, theologians such as Origen and Irenaeus needed to steep themselves in Paul’s epistles. A renaissance of interest in Paul occurred in the fourth and fifth centuries, culminating in Augustine’s battle against Pelagius, with Paul’s doctrine of grace as the prize.

Of course, it is well known that the Reformation of the 16th century was deeply inspired by Paul’s writings, especially Romans and Galatians. In the 20th century, Karl Barth waved Paul’s banner in his Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans, giving birth to a whole new theological movement (Neo-orthodoxy), and most recently, there has been a flurry of new Pauline studies, dubbed dramatically the “new perspective on Paul.”

While any of these encounters with the apostle are worth closer examination, it is Martin Luther’s journey with Paul that continues to stir the imagination for many and kindle a love for his writings.

Luther’s association with Paul began as a love/hate relationship. At the end of his life, Luther would recall this volatile time with vivid immediacy:

I had indeed been captivated with an extraordinary ardor for understanding Paul in the Epistle to the Romans. But up till then it was not the cold blood about the heart, but a single word in Chapter 1, “In it the righteousness of God is revealed,” that had stood in my way. For I hated that word “righteousness of God,” which . . . [I had understood as that] with which God is righteous and punishes the unrighteous sinner. . . . I did not love, yes, I hated the righteous God who punishes sinners, and secretly, if not blasphemously, certainly murmuring greatly, I was angry with God. . . . Nevertheless, I beat importunately upon Paul at that place, most ardently desiring to know what St. Paul wanted! (Luther’s Works, vol. 34, pp. 336–37)

At last, Luther finally understood what Paul wanted: to preach a righteousness that was a gift—a gift by which God mercifully justifies us through faith in His Son. Paul was not describing an implacable standard that could only lead to our condemnation. That would hardly be Gospel, “good news!” Paul was speaking of the righteousness of God that was revealed at the cross—God’s insatiable love for us. When Luther realized this, his whole world turned upside down, the bitter became sweet, and the locked sprang open: “I extolled my sweetest word with a love as great as the hatred with which I had before hated the word ‘righteousness of God.’ Thus that place in Paul was for me truly the gate to paradise” (LW 34:337). While wrestling with Paul, Luther found himself also wrestling with God, and like Jacob of old, Luther would never be the same.

The Trumpet of the Gospel

In many ways, the stage had been set years earlier for this unforgettable encounter. Johann von Staupitz, Luther’s mentor and father confessor, was an avid student of Paul. When the University of Wittenberg was founded in 1502, it was Staupitz who was given the task of assembling the faculty of theology. In the university statutes, Staupitz set the tone by naming St. Paul, “the trumpet of the Gospel” (tuba Euangelii), as the patron saint of the theological faculty.

In many ways, the stage had been set years earlier for this unforgettable encounter. Johann von Staupitz, Luther’s mentor and father confessor, was an avid student of Paul. When the University of Wittenberg was founded in 1502, it was Staupitz who was given the task of assembling the faculty of theology. In the university statutes, Staupitz set the tone by naming St. Paul, “the trumpet of the Gospel” (tuba Euangelii), as the patron saint of the theological faculty.

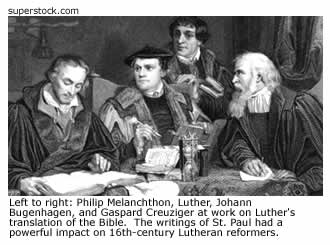

When Staupitz gave Luther his teaching position, Luther had already exhibited a passion for Paul’s theology. After his introductory lectures on the Psalms, Luther began to tackle Paul’s epistles one by one. First he lectured on Romans, then on Galatians, then on Hebrews (which, at the time, was thought to have been written by Paul). His students were completely enamored with this curricular

regime and began to promote Pauline studies among the other faculty. Others then began to lecture on Paul as well, the most notable being Philip Melanchthon, the young Greek professor. So it was that the study of Paul became part of the reforming program of Wittenberg.

But there was also a very personal dimension to Luther’s estimation of Paul. Luther began to see himself—his own life, struggles, and vocation—in light of the apostle’s life. Like Paul, he was an embattled man. Like Paul, his zeal for the Gospel brought him into conflict with those who would compromise its message or obscure Christ. Like Paul, God’s grace had called him to take up the pulpit and the pen in order to proclaim the folly of the cross.

But there was also a very personal dimension to Luther’s estimation of Paul. Luther began to see himself—his own life, struggles, and vocation—in light of the apostle’s life. Like Paul, he was an embattled man. Like Paul, his zeal for the Gospel brought him into conflict with those who would compromise its message or obscure Christ. Like Paul, God’s grace had called him to take up the pulpit and the pen in order to proclaim the folly of the cross.

Even Paul’s remarkable conversion served as a model, so that Luther would often preach on the consolation that such an example of God’s grace to sinners offers: “It was, indeed, a truly great and comforting miracle how our Lord God converts the very man who raged so furiously against and had so determinedly persecuted Christ and his Christendom” (Sermons of Martin Luther: House Postils 3:269). Perhaps, at times, Luther would confuse his own context with Paul’s. But he would nevertheless see a clear confluence of purpose.

Much of Paul’s life seemed analogous to Luther’s own. As the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge would later exclaim, “How dearly Martin Luther loved St. Paul. How dearly would St. Paul have loved Martin Luther! And how impossible that either should not have done so.” Indeed, in Paul Luther found a kindred spirit.

But ultimately it was with the message of St. Paul that Luther fell in love. The attributes and analogies are fine and good, but Paul was an apostle because of what he preached. Luther acknowledged with gratitude that as bearer of the Gospel to the Gentiles, Paul was his spiritual father as well as that of his fellow Christians in Germany: “We must confess we are [Paul’s offspring], for he brought us all, by the Gospel to Christ. . . . As a result Paul is the master who teaches us, for we are Gentiles” (House Postils 3:269).

To You, for You

The clarity of this message gave Paul’s writings a peculiar importance for Luther. Thus his opening remarks in his preface to Romans: “This epistle is really the chief part of the New Testament, and is truly the purest Gospel” (LW 35:365). Because Paul not only spoke of Christ and what He has done, but explicitly connects these facts to you, as things that Christ has done for you, Luther regarded the writings of Paul to be the Gospel, perhaps even more so than those books that are called “Gospels.” After all, though there are four “Gospels,” there is in fact only one Gospel—only one message that is truly “good news”—and this can be found throughout the Scriptures.

The epistles of St. Paul . . . far surpass the other three gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke. . . . [they] are the books that show you Christ and teach you all that is necessary and salvatory for you to know. (LW 35:362)

In Paul’s epistles Luther also notes, “You do not find many works and miracles of Christ described, but you do find depicted in masterly fashion how faith in Christ overcomes sin, death and hell, and gives life, righteousness and salvation. This is the real nature of the Gospel.”

Luther found Paul himself making this distinction when in Galatians he distinguished his own authority from the message of the Gospel: “But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach to you a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let him be accursed!” (Gal. 1:8). The authority of Paul as an apostle lay in what he preached, not simply that he preached. And it was because Paul decided to know nothing but Jesus Christ and Him crucified (1 Cor. 2:2), that his letters are for Luther such a wellspring of the Gospel.

Luther’s journey with Paul continued life long. Sometimes he could speak of his society with the apostle in the most intimate of terms, even as a kind of courtship—after all, Galatians was his “Katie von Bora” (LW 54:20). Tracing the course of Luther’s work as a reformer, one cannot help but see how much he valued the companionship of Paul. After Luther had been cast into the limelight and become one of the most famous (or infamous!) figures in Germany, his very first major publication effort was to revise and print his lectures on Paul.

In 1519, his commentary on Galatians appeared. The Epistle to the Romans he handed over to Melanchthon, who lectured on it repeatedly at Wittenberg. Over a decade later, Luther would publish another commentary on Galatians, the result of another set of lectures. Nevertheless, Luther never thought he could exhaust Paul, nor did he ever think he could provide the definitive interpretation. Instead, Paul was to be a companion for all Christians, in all ages. And in that close society one would find more than an apostle and more than a friend, but the very Christ and Savior who loved him and all people so much that He died and rose again. For this reason, at end of his preface to that first Galatians commentary, Luther invites all to take this journey:

I have had only one aim in view. May I bring it about that, through my effort those who have heard me interpreting the letters of the apostle may find Paul clearer and happily surpass me. But if I have not achieved this, well, I shall still have wasted this labor gladly; it remains an attempt by which I have wanted to kindle the interest of others in Paul’s theology; and this no good man will charge against me as a fault. Farewell. (LW 27:160)