by Dr. Paul L. Maier

Easter is the ultimate test of faith. The one great watershed that ultimately divides believers from unbelievers is the resurrection of Jesus Christ. As St. Paul put it so categorically in 1 Cor. 15:14: “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain.”

You can’t have it both ways: Either Jesus actually rose from the dead, or He did not. The various middling alternatives–He rose in spirit rather than body and all the many variations on that theme–are quite illogical and extremely unsatisfying.

Nothing in this world’s past or present is of more importance or has caused more controversy than the Resurrection event. So, you would imagine that every last shred of evidence on what happened in Jerusalem at the first Easter would by now have been processed logically, examined carefully, and then believed or disbelieved.

Nothing in this world’s past or present is of more importance or has caused more controversy than the Resurrection event. So, you would imagine that every last shred of evidence on what happened in Jerusalem at the first Easter would by now have been processed logically, examined carefully, and then believed or disbelieved.

Astonishingly, this is not the case. Critics of Christianity have repeatedly preferred fancy to fact in their attempts to discredit the Resurrection, while Christians have not used all the evidence available in affirming it.

Explaining Away the Resurrection

Those who deny the physical resurrection of Jesus have offered a series of imaginative suggestions to account for the phenomena cited at the close of the four Gospels. All are testimony to human ingenuity, but also to human stubbornness in refusing to deal logically with the evidence. Here are the prime examples:

The stolen-body theory:

The disciples removed Jesus’ body so that they could hatch the myth of a risen Christ, a view as old as Matthew 28 or older.

But who would have had the motives to do this? Certainly not the Eleven, who were hiding in fear of receiving the same treatment as Jesus. And even if they had suddenly turned that brave, how could they have succeeded in stealing a body from a guarded tomb?

The wrong-tomb theory:

The women of Easter morning got their directions crossed and stumbled upon an open tomb instead of the one in which Jesus was laid to rest.

But afterwards, surely, Jesus’ opponents would have directed the dear ladies to the proper tomb in order to scotch any claims of a resurrection. Not for nothing do all three Synoptic Gospels add an otherwise unnecessary verse, such as Luke 23:55: “The women … saw the tomb and how His body was laid in it.”

The swoon or Jesus-never-died theory:

Jesus only appeared to die, perhaps from the effects of a narcotic or other drug that He received on the cross, but He revived in the cool of the tomb and left it Sunday morning either under His own power or with the assistance of friends.

This, however, founders on the fact that the Romans–grimly efficient when it came to crucifixions–made assurance doubly sure that the victim didn’t pretend death: A pike went through Jesus’ heart.

The hallucination theory:

Confronted with an empty tomb, the women later claimed to see visions of Jesus through “wish fulfillment,” and the disciples and other early Christians picked up on this via psychological contagion.

Yet 500 or more saw the risen Christ in Galilee, according to St. Paul (1 Corinthians 15), and they would have had to experience mass hallucination in order to have seen Him. But there is no such thing.

Have you had enough? Well, please permit one more.

The lettuce theory:

A gardener in the tombs area was so piqued at curiosity-seekers trampling over lettuce seedlings he had planted around Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb that he removed the body of Jesus and reburied it elsewhere!

Crude as this one sounds, it is one of the earliest of these pathetic hypotheses, and the church father Tertullian (circa 155–230) himself records it.

Other, even more fanciful flights of the imagination could be listed. But all these “explanations” have three things in common: They all are illogical, raising more problems than they solve, and are easily disproven; they all contradict crucial points of evidence in the Resurrection accounts; and they all posit a missing body, an empty tomb.

This last point is of enormous importance, though it is generally overlooked.

Admitting an Empty Tomb

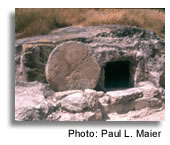

Rather than using any of the specious arguments above, would it not have been a much more effective thrust against Christianity to claim that Jesus’ body was never missing, that it lay in Joseph’s sepulcher all the while? Astonishingly, this argument was never used–and for good reason. There is compelling evidence outside the Gospels that Jesus’ tomb was indeed empty on Resurrection morning.

The circumstantial evidence for the empty tomb is overpowering. It deals with the question: “Where did Christianity first begin?”

To this the answer must be: “Christianity and its core proclamation of Jesus’ resurrection could only have arisen at one spot on earth–the city of Jerusalem.” But this is the very last place it could have originated if the decomposing body of Jesus of Nazareth were still inside Joseph’s tomb for all to see. That would immediately have snuffed out the flame of an incipient Christianity whose central claim was Jesus’ resurrection!

What happened in Jerusalem during the weeks following the first Easter could have taken place only if Jesus’ body actually was missing. Otherwise, the Temple authorities, in their confrontation with the apostles, would simply have aborted the movement by walking over to the sepulcher of Joseph of Arimathea and unveiling Exhibit A. They didn’t do this, because they knew the tomb was empty. Their official explanation for that was simply that the disciples had stolen the body. This was a solid–no, blatant admission that the sepulcher was indeed vacant.

Extrabiblical Evidence

The objection, of course, is that the presumed failure of the authorities to produce Jesus’ body rests only on New Testament sources biased in favor of Christianity. True, it rests on them, but not only on them. In my book In the Fullness of Time I present some important, yet long overlooked, evidence on this issue deriving from purely Jewish and Roman sources, ranging from the first-century Jewish historian Josephus to a fifth-century compilation called Toledoth Jeshu.

What is important about these secular sources–all of which admit an empty tomb–is that they deliver this positive evidence even though they are hostile sources. And that makes theirs the strongest sort of historical evidence. Historians call this interpretive tool “the criterion of embarrassment,” which is a self-authenticating proof. Put simply, if a source concedes something decidedly not in its favor, then that something must be factual and true.

Well into the second century A.D. and long after Matthew recorded its first instance, the Jerusalem authorities continued to admit an empty tomb by ascribing it to the disciples’ stealing the body. In his Dialogue with Trypho, Justin Martyr, who came from neighboring Samaria, reported in about A.D. 150 that Judean authorities even sent specially commissioned agents across the Mediterranean world to counter Christian preaching with exactly this explanation of the Resurrection.

Does any early source claim that Jesus’ tomb was still occupied after that first Easter Sunday? The answer is no. For that matter, does any later source make that claim? No, not to my knowledge, even though any later such claim would have less than marginal significance. Rather, all the sources agree that the tomb was empty.

Accordingly, if all the evidence is weighed carefully and fairly–and using the canons of historical research–one cannot but conclude that the sepulcher of Joseph of Arimathea in which Jesus was buried on Friday was truly empty on the following Sunday morning. And no shred of evidence has yet been discovered anywhere that would disprove this statement.

Does this, then, prove the Resurrection?

No, certainly not. An empty tomb does not, in itself, prove a resurrection. But the reverse is true indeed. A physical resurrection would require an empty tomb as its first symptom, since any occupancy would immediately disprove it. There are, of course, a host of positive arguments and proofs that Jesus did rise from the dead, quite apart from the empty-tomb argument. You know them from sermons on the Resurrection.

It is happily astonishing, then, that the most incredible claim in history–someone rising from the dead–not only cannot be disproved, but best accounts for a momentously missing body that first Easter. “The mystery of the missing body”? It’s no mystery for Christians. He is risen indeed!

Dr. Paul L. Maier is second vice-president of The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, professor of ancient history at Western Michigan University, and author of In the Fullness of Time–A Historian Looks at Christmas, Easter, and the Early Church and many other books. This story appeared in the April 2007 Lutheran Witness. LCMS congregations may reprint this article for parish use. All other rights reserved. Text copyright © 2007 by Paul L. Maier. Photo copyright © 2009 by Paul L. Maier.