by Douglas Campbell

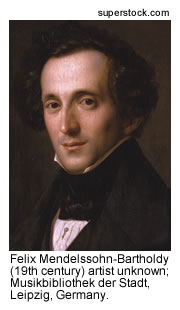

Two generations junior to Bach, Felix Mendelssohn made significant contributions to western music and Lutheran hymnody during his short life.

This past Feb. 3 marked the 200th birthday of a composer of exceptional talent, deep faith, and high character. Often overshadowed in our Lutheran music tradition by the great J.S. Bach, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) is described as “the Classical Romantic”—linking the Classical ideal of form with the Romantic emphasis on expressiveness in music. In addition to “rediscovering” Bach, Mendelssohn enriched not only the music of his own time but also of ours, in church as well as in the salon and concert hall.

This past Feb. 3 marked the 200th birthday of a composer of exceptional talent, deep faith, and high character. Often overshadowed in our Lutheran music tradition by the great J.S. Bach, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) is described as “the Classical Romantic”—linking the Classical ideal of form with the Romantic emphasis on expressiveness in music. In addition to “rediscovering” Bach, Mendelssohn enriched not only the music of his own time but also of ours, in church as well as in the salon and concert hall.

A Vibrant Childhood

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn, born in Hamburg Feb. 3, 1809, of Jewish descent, was the second child and elder son of Abraham and Leah Mendelssohn. Their surname was already well-known—-Abraham’s father, Moses Mendelssohn, gained fame for his Jewish philosophical writings and translation of the Pentateuch. Both Abraham and Leah were secure financially, and several years after they were married, they established a home in Berlin.

The Mendelssohn children were first home-schooled by their parents and later by private tutors. Both their mother and the family’s music teacher had been pupils of one of Bach’s students. Opportunities abounded elsewhere in Mendelssohn’s youth: Composers, scientists, artists, and architects frequented the family home, and travel included Paris, Switzerland, Britain, and Italy. Years later, Felix’s nephew wrote, “Without his father, Felix Mendelssohn would never have become what he was.”

In 1816, Abraham and Leah Mendelssohn converted their family to Christianity, adding the last name Bartholdy. Although this came about largely because of ethnic social pressure, subsequent years reveal a Christian faith genuinely embraced by Felix and his siblings. The Mendelssohn children were baptized on March 21, 1816, when Felix was seven. His confirmation confession from September 1825 opens with John 3:16.

The Blessings of Family

From childhood Felix and his older sister, Fanny, formed a “mutual admiration society.” (Their mother facetiously commented, “They are really vain and proud of one another.”) Sibling relations were close: At the first performance of the oratorio St. Paul in 1836, Fanny sang in the chorus while brother Paul and his wife attended.

“There are no husbands who love their wives as much as Felix loves you,” penned Mendelssohn’s sister, Rebecca, to Cecile Jeanrenaud. United in a happy marriage in 1837, Felix and Cecile enjoyed art, studying English, the outdoors, and reading together.

They had five children. Mendelssohn referred to his children as a “great blessing.” Family letters record him teaching them math, geography, Greek, and music (naturally), reading them “Rumpelstiltskin,” and dispensing discipline.

As a musician, Mendelssohn gave his first public concert when he was nine years old. Compositions began at a young age with numerous works being completed as a teenager. As a conductor, composer, pianist, and organist, Mendelssohn was regularly in demand during his lifetime, with offers from places as far away as New York. More famous appointments included the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra, the Birmingham Festival in England, and service to the King of Prussia. Casual concertizing included Sunday afternoons in the family’s Berlin home; a 19th-century “jam session” with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert; and playing a broken, borrowed fiddle for friends at a bonfire.

Faith and Music

A contemporary stated, “[Mendelssohn] believes firmly in his Lutheran creed.” His manuscripts are initialed with the prayers L.e.g.G. (Laß es gelingen, Gott: “Let it succeed, God”) or H.D.m. (Hilf Du mir: “Help Thou me.”)

We can laud Mendelssohn’s opinion of the Word and of music. Consistent with Heb. 4:12, “The Word of God is living and active,” he wrote: “When composing, I usually look up the Bible passages myself,” and “I have felt with fresh pleasure how forcible, exhaustive and harmonious the Scripture language is for music to me. There is an inimitable force in it.” Reflecting Ps. 33:3, “Sing to Him a new song; play skillfully, and shout for joy,” Mendelssohn wrote: “I take music in a very serious light, and I consider it quite inadmissible to compose anything that I do not thoroughly feel,” and “Every kind of music ought . . . to attend to the glory of God.”

Mendelssohn composed choral settings of the Psalms and liturgy and cantatas on Lutheran chorales such as “O Sacred Head, Now Wounded” (LSB 449), “Jesus, Priceless Treasure” (LSB 743), and “From Heav’n Above to Earth I Come” (LSB 358).

His Organ Sonata No. 1 employs the tune for “The Will of God Is Always Best” (LSB 758) and Organ Sonata No. 6 showcases variations on “Our Father” (LSB 766), Luther’s catechetical hymn on the Lord’s Prayer.

The distribution of five chorales in the oratorio St. Paul helps recount the history of the Apostle to the Gentiles. The 1846 oratorio Elijah is considered by some to show that prophet as a type of Christ. (Elijah’s confrontation with the priests of Baal is particularly dramatic!)

The distribution of five chorales in the oratorio St. Paul helps recount the history of the Apostle to the Gentiles. The 1846 oratorio Elijah is considered by some to show that prophet as a type of Christ. (Elijah’s confrontation with the priests of Baal is particularly dramatic!)

Symphony No. 5, Reformation, concludes powerfully with the “Battle Hymn of the Reformation,” “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” (LSB 657). This music was intended to commemorate the 1830 tercentennial of the Augsburg Confession.

Mendelssohn received a commission for the 1840 Gutenberg Festival in Leipzig (a center for book publishing), celebrating 400 years of the Gutenberg printing press. At Bach’s own St. Thomas’s Church in Leipzig, Symphony No. 2, Hymn of Praise premiered, featuring “Now Thank We All Our God” (LSB 895) and opening and closing choirs declaring Psalm 150: “Let everything that has breath praise the Lord! Alleluia!”

Cultural Fixtures

Some of Mendelssohn’s work has become a fixture in western culture. The “Spring Song” for piano is a background music staple in classic Saturday morning cartoons. Many couples exit their church ceremony into married life to his “Wedding March,” incidental music written for Shakespeare’s play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

At the 1840 Gutenberg Festival, Mendelssohn also composed a patriotic tune for a chorus of 200 men and brass band. The tune was for the dedication of a statue of

the printer. Mendelssohn said: “I am sure that piece will be liked very much by singers and by hearers but it will never do to sacred words.” Fifteen years later, it was combined with a Charles Wesley text, creating a popular carol. The ubiquitous presence of “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” at Christmas might surprise Mendelssohn today.

An Inspiring Legacy

In spite of anti-Semitic disparagement following his 1847 death and a Nazi ban in the 20th century, Mendelssohn’s work has endured. His music totals more than 250 pieces from all genres, many popular in the modern repertoire. Besides composition, he is credited with coining the oxymoron “song without words,” which persists in musical terminology. Modern concert programming is also attributed to him, where music is played from a wide variety of periods at a single sitting. His keen interest in Bach, fueled by his parents and teachers, led to the performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in 1829. At the time, Bach’s work was commonly perceived as outdated drudgery. Mendelssohn’s presentation of the piece after 80 years in obscurity spurred the “Bach revival.”

The life, influence, and especially the music of Mendelssohn serve as an inspiration to us in 2009. Take the opportunity this year to explore and discover the music of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy—the “other” Lutheran composer.

Our Hymns: Much More Than Words and Music

Every hymn is much more than words and music. Each hymn is a skilled instructor, a fascinating time capsule, and a spiritual mentor. Each and every hymn in our hymnal is there because of a wonderful interaction of creativity, devotion, and history. Knowing the resources contained in the pew edition of the hymnal and also located in its support volumes can lead to an expanded appreciation of the blessings contained within the hymn itself. The process of discovering those blessings begins by taking a closer look at the hymn on the hymnbook page.

Not only are there texts and the music notes on a hymnal page, there is other information to present a fuller picture of the work. The names of the text writer, musical composer, and other people who have worked with the words and music, such as translators and arrangers, are noted beneath the hymn. Each of those people is a special contributor and has a singular life story. As we learn about them, these gifted people become skilled instructors for us.

The life story of Felix Mendelssohn is a good example of that kind of inspiring instruction. Mendelssohn not only composed music, he enriched the faith of countless Christians through his broader musical skills. In the back of our Lutheran Service Book (LSB) is a set of indexes which share the scope of work of a given contributor to the hymnal. If you look under Felix Mendelssohn (on p. 1005) you will discover that not only did he compose the tune for “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” (LSB 380) and one of the melodies for “Grant Peace, We Pray, in Mercy, Lord” (LSB 777), he supplied the setting of the hymn tune “Munich” which is used three times in LSB: hymns 523, 606, and 658.

In its way, each of the hymns in the hymnbook is a fascinating time capsule. The words were written in a specific time and place in the history of God’s people. The tunes were composed in various eras in the rich history of world music. Coming to understand more about that history is an enriching experience. At the present time, the LCMS Commission on Worship and Concordia Publishing House are cooperating on the publication of the Lutheran Service Book Hymnal Companion. This volume, written for both professionals and the wider membership of the Church, will be sharing the amazing history of our hymnody and telling the stories of the people behind the words and music. The Hymnal Companion will be available throughout the Church in June 2010.

As presented in LSB, each hymn serves as a spiritual mentor. At the end of each hymn is a listing of Bible texts that relate to the theme of the hymn. These can be studied in a devotional manner. Also a newly released resource, Lutheran Service Book Concordance, provides further opportunities for discovery and growth by listing each word in every hymn in LSB in an easily understood alphabetical sequence. Choosing a word such as “mercy” or “peace” or “blessings” or “prayer” and then looking up the hymn stanzas in which they are found can be a rewarding devotional exercise. Each hymn is so much more than just words and music! Start to make that discovery for yourself soon!

— By Dr. Gregory J. Wismar