by Thomas Egger

The Bible compares Jesus to a tent. When St. John writes, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14), the word for “dwelt” directly recalls the Old Testament tabernacle, the holy tent in which God resided in the midst of the children of Israel.

For some people, a tent may evoke unpleasant memories: midnight thunderstorms, strange sounds, stiff mornings and soggy bedrolls. But for the people of Israel, God’s tent in their midst was a profound gift and blessing. As Christians have celebrated Christmas throughout the centuries, we have often compared the precious gift of Jesus’ birth with this Old Testament gift — the tabernacle, the tent of God’s presence.

Heaven on earth

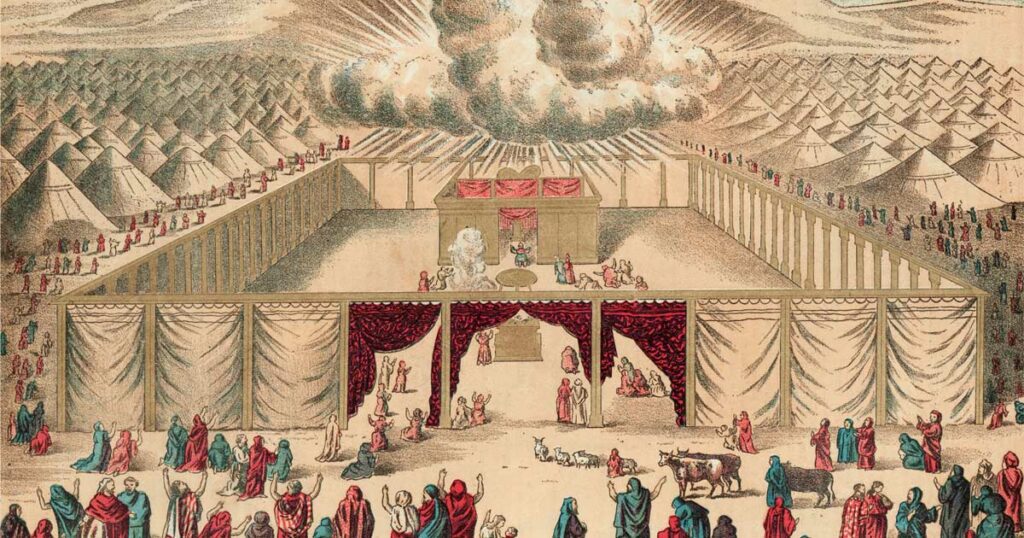

The tabernacle was simple and portable, yet also beautiful, holy and heavenly. The tabernacle’s perimeter, 150 by 75 feet, was marked by curtain panels 7 feet tall. The outer curtains surrounded a courtyard that contained another tent, the Holy Place, and within the Holy Place, separated by a veil, was the Holy of Holies. There dwelled the living God, enthroned upon the ark of the covenant.

Endowed with the Spirit of God, skilled craftsmen fashioned the tabernacle furnishings using precious metals and finely woven fabrics. Many furnishings glistened with gold overlay, and the lid on the ark, where the high priest poured the blood of atonement, was solid gold.

Its decorations marked the tabernacle as heaven on earth. The curtains and veil were embroidered with pictures of cherubim, and two cherubim of hammered gold stood upon the lid of the ark. These images declared, “Here you are entering heaven itself. Here you are meeting with the God of heaven. Here heaven has come down to earth, and God has come near to you, in holiness and mercy.”

A new Garden of Eden

The tabernacle decorations also marked it as a new Garden of Eden. Before the tabernacle instructions in Exodus, the Bible’s only mention of cherubim is when God stations them with flaming swords at the entrance of the Garden of Eden (Gen. 3:24). When the world was young, our first parents met with and spoke with God in Eden. But when they sinned, God exiled them from the garden. The images of cherubim in the tabernacle reminded the people that their sin once separated them from God.

Yet these tabernacle cherubim also signified something else. It’s as though they declared, “God is restoring to you the Eden that you forfeited. Cherubim with flaming swords prevented your return to Eden, to God, to eternal life, but God is restoring the blessings of Eden for you. He is ‘planting’ this tabernacle as a place where God will once again dwell with man, and man with God.”

Consider what a remarkable moment it was — in the whole history of the world — when the tabernacle was completed and the glory of God descended from heaven and filled it (Ex. 40:33–38). For many long centuries, our race had spread out across the world, exiled from the garden and from the God who had created us. At times, God had graciously appeared and spoken to humans: to Noah, Abraham and others. He had appeared and spoken, but then disappeared and remained silent, often for many years. But in the tabernacle, God came to stay. God pitched His tent in the midst of His people. He dwelled with them upon the earth. God once more had an “address” in the world, and that address was “in the midst of Israel.”

God dwells with a stiff-necked people

The Book of Exodus tells the story of the tabernacle. In Exodus, God fulfilled His ancient promises to the descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (Israel). God increased their numbers greatly and rescued them from the bitter slavery under Pharaoh. Having brought Israel out of Egypt, God met with them at Mount Sinai. He made covenant promises to them that He would be their God and they would be His people, and that He would lead them up to the Promised Land. He gave Moses detailed instructions for the construction of the tabernacle. For God did not perform His great wonders against Egypt simply to give Israel a different land in which to live, but so that Israel could know and live with Him. God told Moses:

[At the tabernacle] I will meet with you, to speak to you there. There I will meet with the people of Israel, and it shall be sanctified by my glory. I will consecrate the tent of meeting and the altar. … I will dwell among the people of Israel and will be their God. And they shall know that I am the Lord their God, who brought them out of the land of Egypt that I might dwell among them. I am the Lord their God. (Ex. 29:42–46)

God’s words to Moses describe three aspects of the tabernacle. First, it was a dwelling place, where He would dwell among the people as their God. The Hebrew word translated as “tabernacle” comes from a root word meaning “to settle, abide, dwell.” Second, it was a tent of meeting, that is, the place where God would regularly meet with His people. Third, it was a sanctuary, that is, a holy tent, holy ground, a holy place made holy by God’s glorious, holy presence.

This third characteristic, the tabernacle as holy ground, highlights a problem. If the holy God had driven Adam and Eve out of the garden because of their sin, how could the holy God now dwell in the midst of Israel? How could they enter the presence of the God of heaven, or enter the gate of this new Garden of Eden? Exodus points out that the answer does not lie in the faithfulness or moral improvement of the children of Israel.

The first half of Exodus seems to fly by with interesting episodes and adventures. But then come the tabernacle chapters (Exodus 25–40), and it becomes heavy slogging for the reader, with laborious details of poles, rings, cubits, ephods, tanned ram’s skins and so forth. However, right in the heart of all of this tabernacle instruction and construction stands one vivid event: Israel’s worship of the golden calf (Exodus 32–34). Their sin threatened to derail the plan of the holy God to dwell in their midst: “You are a stiff-necked people; if for a single moment I should go up among you, I would consume you” (Ex. 33:5).

God indicts and threatens His people. But it is not the Lord’s final word on the matter. Moses pleads with God on behalf of sinful Israel. And God reveals the breathtaking depth of His mercy and compassion, proclaiming aloud His divine name and declaring Himself “a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, keeping steadfast love for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin” (Ex. 34:6–7).

In light of this shocking manifestation of the people’s sin, the laborious details of the tabernacle find their true meaning; this tent would be the place where God makes His people holy. The boundaries established by the tent’s various curtains and veils proclaimed that the time of full reunion with God had not yet come. God’s people would need mediators (like Moses) to come before God on their behalf, so God gave instruction to consecrate priests to minister in the tabernacle. The tabernacle’s great bronze altar, the golden lid on the ark and the sacrifices would provide blood atonement so that unholy, stiffnecked sinners might be forgiven and dwell with God. Finally, through these appointed means, the glory of the holy God would not consume the people but sanctify them.

Jesus tabernacles among us

The Old Testament tabernacle was built by forgiven sinners, and it was the gift of God. The God who dwelled with them abounded in grace and truth, and His glory filled the tent. What a remarkable moment that was — in the whole history of the world.

But Christmas is a yet more remarkable moment.

In the fullness of time, the Son of God was born as the Son of Mary (Gal. 4:4). “The Word became flesh and [tabernacled] among us, and we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, [abounding in] grace and truth” (John 1:14).

Jesus came as a new and better tabernacle. He came to dwell with us. Heaven came to earth, the bliss of Eden being restored, God walking with us again. Immanuel. He meets with us, speaks to us, forgives us and makes us sinners holy. No curtain or veil stood between the Lord Jesus and sinners. No priests had to approach Jesus on sinners’ behalf. Tax collectors sat at table with Him. A prostitute, grateful for forgiveness, wet His feet with her tears and dried them with her hair (Luke 7:36–40). Crowds of sinners flocked to Him and pressed around Him. And the glory of the holy God, manifested in Jesus, did not consume them but sanctified them.

Marvel again this Christmas at what happened that night long ago, as the skies above Bethlehem were embroidered with angelic figures, rejoicing that the glorious God of heaven has now come with His peace to men on earth.

Using bronze and gold, wood and blood, God provided blood atonement for sinful Israel in the tabernacle. But here in the manger lies the new and better tabernacle, built not with poles, rings and ram’s skins, but with human flesh, born of Mary. With this flesh, He poured out His lifeblood once and for all to atone for stiff-necked sinners.

The Old Testament tabernacle lasted only for a time. King Solomon replaced it with a similar but more permanent structure: the temple in Jerusalem. But even the temple was not permanent; the Babylonians destroyed it in 586 B.C. And though it was later rebuilt, the Romans finally destroyed it again in A.D. 70.

Jesus is the new and better tabernacle and abides with us always. Having raised up the “temple” of His body on the third day (John 2:19), He is our Immanuel (“God with us”) forever (Matt. 1:23). He has promised to be with us always, to the end of the world (Matt. 28:20). Where two or three are gathered in His name, He is present (Matt. 18:20). In His Word and Sacraments, He regularly meets with us. His glorious holiness does not consume us but makes us holy. Throughout the wilderness pilgrimage of our lives, Jesus camps with us until we reach the Promised Land.

One day soon, Jesus will appear in great glory with all His holy ones. Our new and better tabernacle will come to us and bring us to Himself forever. Heaven will be joined with earth, a new Garden of Eden. The cherubim will sheath their fiery swords forever, and Jesus will bring us in. Our Lord Jesus, who was enthroned in the Holy of Holies of the tabernacle, will sit upon His great throne in that glorious new world. With a loud and joyful voice, He will declare, “Behold, the dwelling place [tent] of God is with man. He will [tabernacle] with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God” (Rev. 21:3).

Merry Christmas, you redeemed of Christ. Jesus, the new and better tabernacle, has come to dwell with you forever.

This article originally appeared in print in the December 2020 issue of The Lutheran Witness.

Thank you for this article. Further to the significance of the Old Testament Tabernacle and it symbolizing Jesus, why is it that the connection between Jesus, our Tabernacle and Sukkot (Feast of Taberncles/Booths) is overlooked? The connection of Jesus being The Passover Lamb has not been lost so why is there such a lack with Christians in general to connect the other Jewish observances to Jesus? Constantine set the Christmas date by combining it with pagan customs. Why do we not take the details in the Bible to acknowledge how brilliant God is and how he has orchestrated history and the Bible to artistically and strategically connect different historical events? There are clues that God leaves in the Bible that leads to the conclusion that Jesus was born during the time of Sukkot. If we are earnest in searching the scriptures and loving truth then we must be willing to let go of our own notions and traditions and embrace what the Bible is telling.us.

An outstanding explanation on God’s love and presence among us from the beginning. Thank you Rev. Egger.

Thank you for the full and lasting story of God love for us. Peace to you and love of God forever.