Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion!

(Zech 9:9)

Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem!

Behold, your king is coming to you;

righteous and having salvation is he,

humble and mounted on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

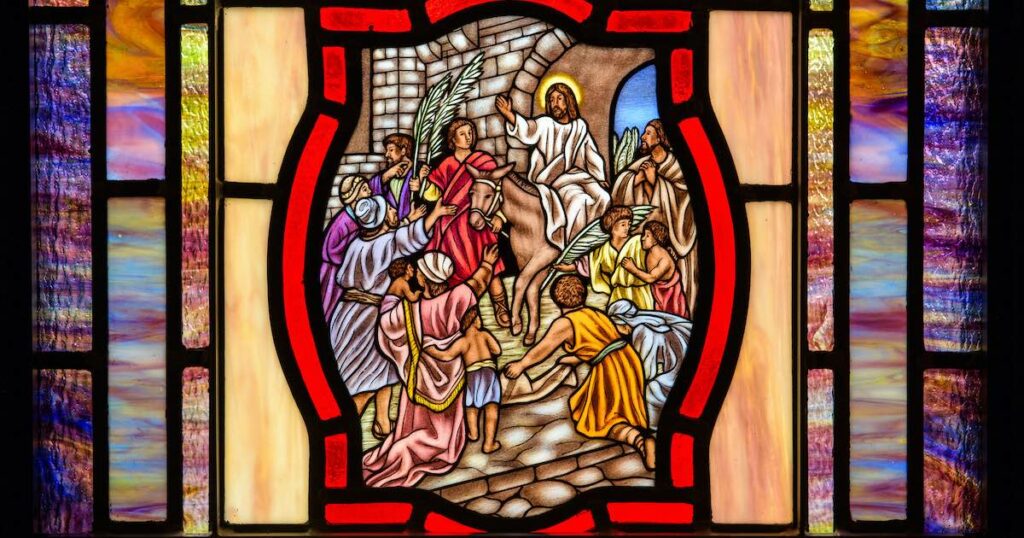

Palm Sunday is one of those triumphal days where prophecy and fulfillment beautifully are upheld side by side. With palm branches in hand, the church reenacts Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem where He “ride[s] on to die” (LSB 441:2). Behind it all is Zechariah’s prophecy, as if he saw the whole thing ahead of time (which he did). Such a vision led Zechariah and those gathered to hear his prophecy to rejoice. Joy comes with this King, both for Zechariah and for us, whether it’s longing for His coming some 500 years beforehand or longing for His coming some 2,000 years later. We’re all praying, “Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev. 22:20).

In his commentary on Zechariah, St. Cyril captures the comfort and consolation of this announcement that the King comes to us. Cyril (a.d. 376–444), as I noted in the first article, is better known for his theological treatises but his biblical commentary and preaching far outweighs them all. His staunch defense of the two natures in Christ in the face of the Nestorian controversy comes from years of wrestling with the texts of Scripture, and largely on the Old Testament. His formula, “One incarnate nature of God the Word” provided the matrix for the council of Chalcedon (a.d. 451) and formed the basis of our Lutheran confession of Christ. In fact, I first met Cyril in the Lutheran Confessions. It was this passage that first caught my attention:

On account of this personal union and communion of the natures [in Christ Jesus], Mary, the most blessed Virgin, did not bear a mere man. But, as the angel Gabriel testifies, she bore a man who is truly the Son of the most high God. He showed His divine majesty even in His mother’s womb, because He was born of a virgin, without violating her virginity.

(FC SD VIII 24)

Therefore, she is truly the mother of God [Theotokos] and yet has remained a virgin [semper virgo].”

I wondered how we could say these things about Mary — Theotokos and semper virgo. The Lutheran Confessions referenced St. Cyril as our authority here, so I started digging. Here’s a bit of context about Cyril first.

Cyril was born to a wealthy, pious family. When he was seven his uncle, Theophilus was made archbishop of Alexandria. Cyril’s parents sent him there to study at some of the best schools in the world. At age 19, he entered the monastery of St. Macarius, where he studied for six years. In a.d. 403, Cyril was ordained lector in Alexandria and attended the Synod of Oak, where his Uncle Theophilus condemned St. John Chrysostom. His uncle died in a.d. 412 and Cyril was made archbishop of Alexandria (amidst great tensions). The first few years as bishop were turbulent, to put it mildly. After six terrible years of conflict with both Jews and pagans, Cyril enjoyed ten years of peace. From a.d. 418 to a.d. 428 Cyril wrote numerous commentaries on the Scriptures. Then came the ecumenical scandal: the Syrian monk, Nestorius, was appointed archbishop of Constantinople.

Now, if we rank our heretics rightly, Nestorius comes in second only to Arius. While Arius went around telling people that there was a time when the Son wasn’t, Nestorius said that Mary wasn’t Theotokos — the God-Bearer/Mother of God. The gist of it is this: If Mary is not the Mother of God [Theotokos], then Jesus, her Son, is not God. And if Jesus isn’t God, then the cross is ineffective, sin isn’t atoned for, death isn’t defeated, and we are still lost and condemned. Nestorius refused to admit that Mary was the mother of God because He separated the two natures of Christ. For Nestorius, Mary was only mother of the human Jesus, not the divine Jesus. So, while the Blessed Virgin Mary is at the center of the conflict, it’s not really about Mary. It’s about Jesus.

The aftermath of this controversy, as you might expect, was messy. Nestorius was deposed and sent back to the monastery, but his teaching never died out. Sadly, you’ll find it all too often today—its greatest symptom is seen at the altar, whether it is as Jesus said—His Body and His Blood—or not. Finally, on June 27 in a.d. 444, at the age of 66, Cyril died.

In the midst of such opposition, the words of the prophets give great consolation. Cyril found welcome news in Zechariah’s heralding of the coming King. Here’s Cyril:

“Obviously in this he now proclaims the revelation of our Savior, the result being that there is no sign of any problem, the consequent order given to the spiritual Zion necessarily being to rejoice for the reason that all our sadness has also been removed. After all, what continuing basis of sadness could exist, and on what grounds could sorrow be our lot, now that sin has been driven off, death trampled underfoot, human nature called to the dignity of freedom, the gift of sonship conferred as a decoration and given added luster with the heavenly graces from on high?

Now, observe that in giving the good news of our Savior’s coming he immediately summons daughter Zion. So it was quite right for him to bid her rejoice exceedingly and to urge Jerusalem to announce that her king will be coming and be revealed in the flesh, righteous and saving. In other words, Christ has justified us and directed in the path of salvation those who approach him. Furthermore, he is gentle, not proposing the severity of the Law nor punishing with death those who transgress its commandment, but rather saving by his mildness and raising up the lapsed, even be they sinners, since he has come in person as an advocate with the God and Father. We read that “the letter kills but the spirit gives life,” the letter being the Law that punishes, which is a shadow and a type, whereas the spirit that gives life is Christ. We have, in fact, been taught to worship him in spirit and truth; you need no lengthy treatment by way of proving that he was riding on a young foal and in this way entered Jerusalem — the divinely inspired evangelist’s writing to this effect being sufficient for our faith. Christ was seated on the foal, remember, while its mother followed; what happened also gave us an indication of the most important reality. That is to say, Christ rested upon the new people, namely, the one called to the knowledge of the truth after formerly worshipping idols; it was like a kind of foal, as yet untamed, not in the habit of taking the right path — in other words, it lacked guidance in the divine law — yet he who leads everyone to spiritual proficiency destined the foal for himself. On the other hand, it also gave us to understand by mention of the ass which followed that the assembly of the Jews followed in due course, although being the elder in its vocation in terms of time, having been previously called through Moses and the prophets. But since it offended against the saving king, not having accepted the faith, consequently it was right that it should come behind the foal, bringing up the rear, taking second place to those from the nations, the first becoming last.[1]

“Obviously,” Cyril says, the king is Jesus. This wasn’t so obvious, however, for one of his contemporaries, Theodore of Mopsuestia, who stands alone saying, “it is clear that here this refers to Zerubbabel.”[2] Theodore’s point is not that the Evangelist got it wrong, so to speak, but that what the Gospels reveal is the “reality” while the Law (OT) reveals the “outline.” But for Cyril, the “outline” and “reality” are one. What Zechariah saw was the reality as told by the Evangelist: Her king will be coming and be revealed in the flesh righteous and saving.

The comfort that Cyril sees in Zechariah comforts us just as much today. He says, “what continuing basis of sadness could exist, and on what grounds could sorrow be our lot, now that sin has been driven off, death trampled underfoot, human nature called to the dignity of freedom, the gift of sonship conferred as a decoration and given added luster with the heavenly graces from on high?” This is what Zechariah saw: forgiveness, life, and salvation. Our worship “in Spirit and in truth” helps us to recognize that we are included in this saving work of the King. And so we sing:

Ride on, ride on in majesty!

(LSB 441:5)

In lowly pomp ride on to die.

Bow Thy meek head to mortal pain,

Then take, O God, Thy pow’r and reign.

[1] Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on the Twelve Prophets, Volume 3, trans. Robert C. Hill (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2012), 189-190.

[2] Theodore, Commentary on the Twelve Prophets, 366.

“I wondered how we could say these things about Mary — Theotokos and semper virgo.”

Yet, the LCMS, and other Lutherans who claim a quia subscription to the Confessions, don’t seem to say at least one of those things about Mary? (https://www.lcms.org/about/beliefs/faqs/the-bible#siblings)

At least one prominent LCMS pastor has argued that only the German version of the Confessions (or maybe just those of the Formula of Concord and Smalcald Articles) are authoritative and subject of the quia subscription. I disagree, but would be interested in the author’s comment on these points.

Dear Justin,

While the thrust of the argument is not, specifically, a defense of the perpetual virginity of Mary [semper virgo; FC SD VIII, 24], there is ample room in both our Confessions and LCMS history and practice for such a belief. The FAQ cited above seems unaware of Francis Pieper’s statement in his dogmatics text–the same text that nearly all LCMS pastors use in their seminary training–which states, “If the Christology of a theologian is orthodox in all other respects, he is not to be regarded as a heretic for holding that Mary bore other children in a natural manner after she had given birth to the Son of God.” (Christian Dogmatics II:308)

Beyond this, I’d encourage you to read up a bit on the history of the question. I think you’ll find it both interesting and fulfilling. Jerome’s writing against Helvidius might be a good place to start for the early tradition. A more recent work of a scholarly nature is John McHugh’s “The Mother of Jesus in the New Testament.”

Peace!