Artwork and visual symbolism seen in a church building often make a confession long before parishioners hear what is confessed in the liturgy. Some of the symbolic meaning, however, may be lost to us. This is the last of nine articles devoted to those images which we often see — but may not always understand — in the sanctuary.

Christian symbols have been around for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. Most are pictures condensed into a simplified form. Some, however, are simply stylized initialisms, also known as monograms. This emphasis on words should not surprise us.

“In the beginning was the Word.” While it is impossible to wrap our human brains around the idea, our Lord is the Word, and Holy Scripture makes that Word manifest among us. Therefore, many Christian symbols are based on the words of Scripture. They have been boiled down into initialisms and can serve as “captions” as well as the main focus in designs and artwork.

Christograms, monograms of Christ’s name, were among the first symbols to appear in Christian artwork. The Roman Emperor Constantine the Great brought the Chi-Rho, a fusion of the first two characters in the name “Christ,” to prominence, though the symbol pre-dates him.

The Iota-Chi appeared at the same time as the Chi-Rho. It used the first characters of each word in “Jesus Christ.” We sometimes miss this symbol when viewing older pieces of Christian art because it often looks like the spokes of a wheel, and even more so when the symbol is circumscribed by a laurel wreath or decorative circle.

A common monogram in Eastern Orthodox iconography is “IC XC.” It serves the same purpose as the Iota-Chi, but includes the last letters in the name “Jesus Christ.” Artists often place a short bar or decorative “squiggle” above each set of letters to denote them as monograms, as when we add a period to an English abbreviation. It is also common to see this Christogram separated — usually by a depiction of Christ — with the abbreviation “Jesus” (IC) on one side and “Christ” (XC) on the other.

The most common but perhaps least understood monogram often appears in Lutheran churches in the chancel or on the altar itself: “IHS.” It is simply the first three Greek characters in the name “Jesus.” Through the centuries, this monogram has been given different meanings, including “Iesus Hominum Salvator” (“Jesus, Savior of Mankind”), “In Hoc Signo [Vinces]” (“In This Sign Thou Shalt Conquer”), or even the English initialism, “In His Service.” These last three are incorrect and were developed by fringe groups who sought to impose their own meaning on the simple symbol for “Jesus.”

Often this symbol follows proper form, with a line placed over it. When lowercase characters are used, the ascending “h” forms a cross. When uppercase characters are used, artists commonly place a small Latin cross atop the horizontal bar of the “H.”

The Alpha-Omega monogram — expressed as ΑΩ or Αω or αω — is also considered a Christogram because Christ described Himself with this term (Rev. 22:13). The characters are sometimes used alone or with a cross, or are combined with other symbols, including the Chi-Rho. Watch out for the stylized symbol “AM,” which is an initialism of Ave Maria. It often appears similar to ΑΩ but carries a significantly different meaning.

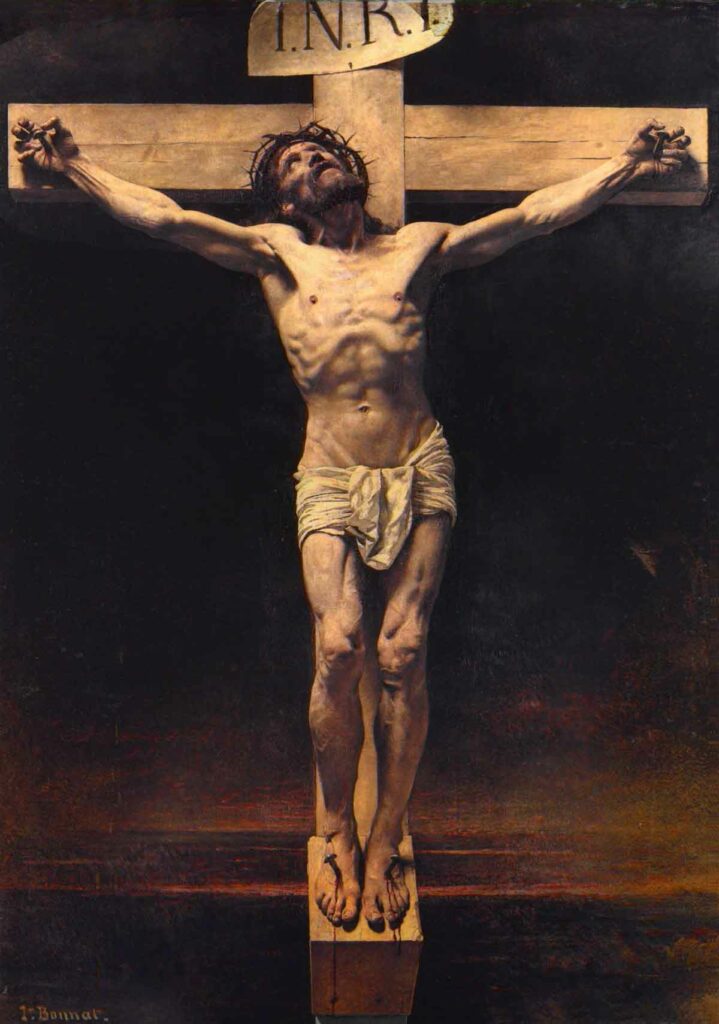

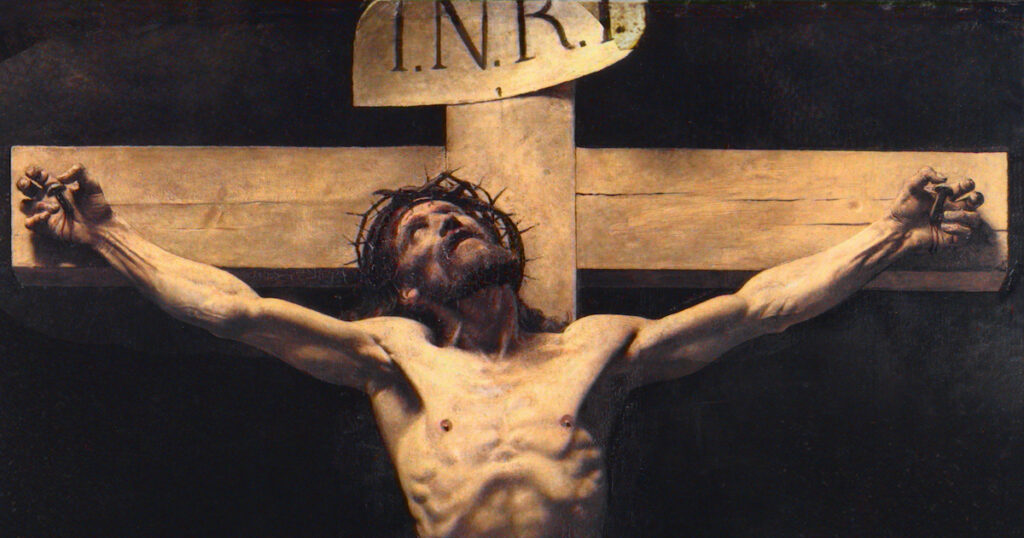

One symbol often seen in depictions of the crucifixion of our Lord is an initialism imposed by Pontius Pilate. “INRI” is an attempt to condense the titulus, or inscription, placed above Jesus’ head. It appears on a placard either in the form of a scroll (historically unlikely) or, sometimes, in the form of a tabula ansata — a wooden placard with handle-like appendages on each side. The expansion of the INRI is “Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum” (“Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews”). The symbol ignores the Greek and Aramaic translations, which were also inscribed on the titulus.

The Eastern Orthodox Church sometimes puts a twist on Pilate’s inscription by replacing “INRI” with “OBCLDXC,” which translates as “The King of Glory.”

Numerous monograms are reserved for Mary, the mother of our Lord. Once in a great while they show up in Lutheran churches but will most likely be restricted to a stylized “M” fused with a cross and triangle to represent the Incarnation. Otherwise, the Marian symbolism is considered excessively Roman.

During the Lutheran Reformation, the “VDMA” cross was developed and used as a monogram on the sleeves of the household of Frederick the Wise. It is an initialism of the Latin phrase, “Verbum Domini Manet in Aeternum” (“The Word of the Lord Endures Forever”), which is based on 1 Peter 1:24–25. Soon after its debut, the symbol found its way onto the armor and weaponry of the Hanseatic League. Today it is making a return on everything from T-shirts to coffee mugs.

Another common abbreviation often found on cornerstones is one of those symbols targeted by secular society as too “churchy.” Inscribed as “A+D” and followed by a year, it is short for “Anno Domini” (“The Year of our Lord”). It not only denotes the dedication date of a church building, but also reminds us that everything — even our years — are our Lord’s.

Every Christian symbol, from the tri-radiant nimbus to the abbreviation for “Christ,” in some way points us to Holy Scripture. While some denominations eschew them, Lutherans view Christian symbols as edifying tools that enrich our understanding of the Word. They are, in essence, a sort of frontlet between our eyes that helps us to ponder the mighty works of our Lord as we sit in the Lord’s house, as we walk by the way, as we lie down and as we rise.

Figure 1: Public domain. Access here.

Are renderings of Christ a graven image? How can a picture be one of God?

Jesus is the image of the invisible God. In the Old Covenant, God had not yet joined himself to humanity, so there could be no image of him. Now that God has manifest himself in the flesh, we can depict that flesh as one of our own.

Thank you so much for enlightening us about the symbols, Christian and non-Christian and how they became what they are. You are so blessed and thank you for sharing your blessing.