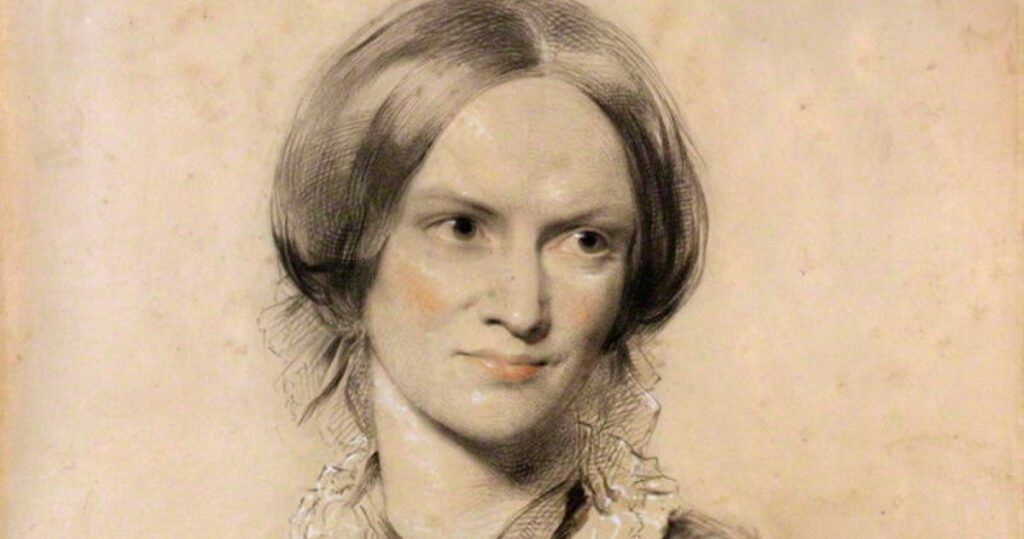

A literary reflection by Molly Lackey on Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. This is the first installment of a new monthly series providing reflections on works of literature from a Lutheran perspective.

Author’s Note: The review that follows will unavoidably involve plot details and “spoilers.” If you wish to avoid these, I recommend closing your browser tab and heading to your local library, bookseller or digital purveyor of fine — and, hopefully, free — public domain titles.

“Conventionality is not morality. Self-righteousness is not religion.”

Thus writes the Victorian English author Charlotte Brontë in her gripping 1847 novel Jane Eyre. With the crisp leaf and cool breath of autumn upon us, now is a wonderful time to revisit — or journey for the first time — into this classic, one which poses some challenging questions to Christian readers, but offers rewarding answers for their toil.

What is real goodness, the story asks. And what is only the appearance of goodness? Are these two always found together? Are they ever?

Jane Eyre is an orphan living among relatives who despise and belittle her, eager for any opportunity to rid themselves of her burdensome presence. She repeatedly deals with exclusion, tragedy and loss, and rarely encounters any friend able or willing to shelter and care for her. Again and again, she faces the same false accusations: Jane is a liar. Jane is an ingrate. Jane is a heathen — Jane isn’t even a Christian.

Jane has faults, but they are not these. Jane is headstrong, willful and emotional. She is sometimes overcome by her feelings. As a girl, she often regrets her emotion-fueled actions, and as an adult she takes pains to address this weakness and seeks forgiveness from those she has harmed. Yet even these characteristics are not, in and of themselves, bad. A woman who recognizes what is right and what is wrong and is willing to stand her ground is God-pleasing, as Solomon himself writes: “Who can find a virtuous woman? For her price is far above rubies. … She girdeth her loins with strength, and strengtheneth her arms. … She openeth her mouth with wisdom” (Prov. 31: 10, 17, 26 KJV).

And yet, because much of what Jane does, says and feels puts her outside of conventional early-Victorian norms for her day, she is maligned, even by those people into whose care God has placed her, like her guardian aunt, cousins and teachers, all of whom are respectable people whose good reputations belie cold, hate-filled hearts.

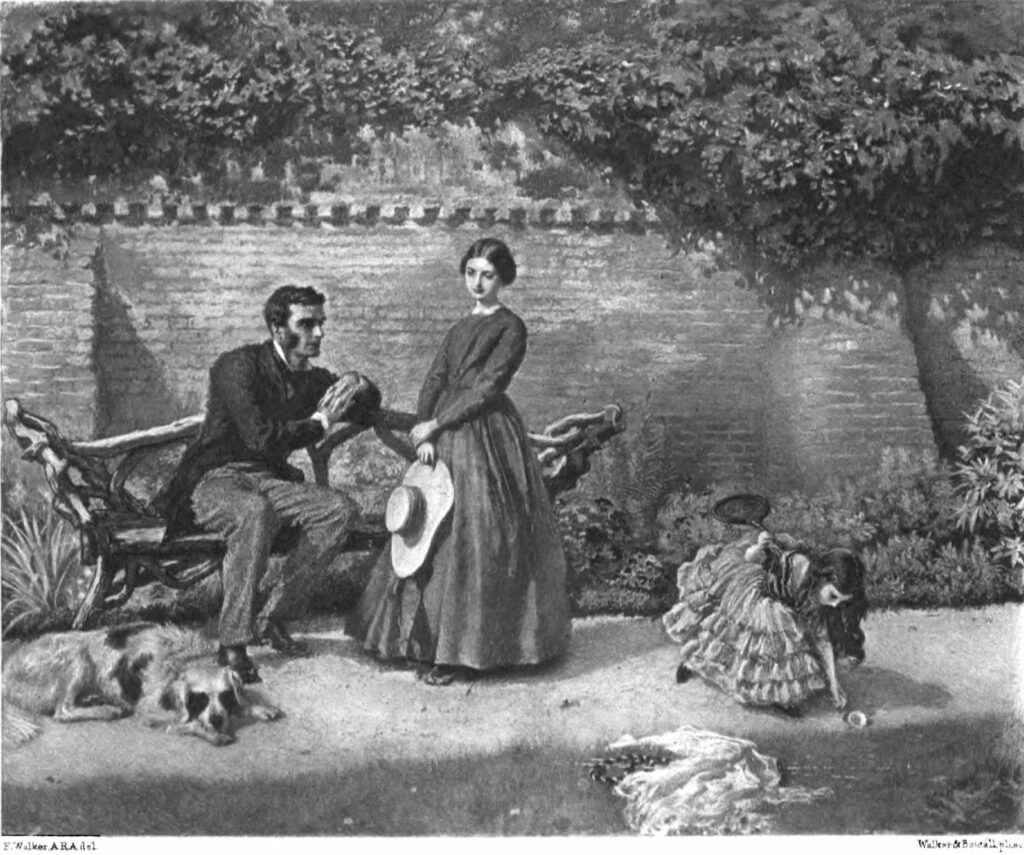

As Jane reaches adulthood, the reader hopes for some improvement in her state, as she accepts a position as governess for a little girl in the care of an absentee gentleman living in the windswept moors of northern England. Her kindness and intelligence win her friends in her new position quickly, despite the hardship she has previously faced. And then comes the real puzzler of the novel: Mr. Rochester.

Rochester is flippant, sarcastic and inscrutable. He is sometimes kind to Jane, sometimes unkind. He has a murky but clearly immoral past. He has fallen into a life of vice. There are some complicating and perhaps mitigating factors: After all, being tricked into marrying an adulterous, sin-loving woman, whom you cannot legally divorce because she has been declared insane, whom you now secretly house in your attic for her own safety and the safety of your household — that’s a situation that would surely strain the moral fiber of even the most pious among us. Nevertheless, Rochester has moments where it is clear that he cares for Jane in a self-sacrificing way, a way that he desired, but was never able, to love his lawfully-wedded wife.

After a brief and atypical courtship, Rochester asks the unsuspecting Jane to marry him. He makes it clear that he is drawn to Jane because of her virtue and her willingness to stand up to him when he is wrong. Finally, it seems that Jane’s unconventional virtue will be rewarded — but it does not last. It is only at the altar that Jane learns that there is, in fact, a known impediment to their marriage. Rochester is enraged, and that night, tries to argue both that his legal wife is, surely, not a wife in any but the most technical sense; and, simultaneously, that it doesn’t really matter if he is a bigamist (or Jane his concubine), because they really love each other, and her good nature will help him attain goodness after all, even if it is an unconventional arrangement.

Brontë really shines in showing how Jane grapples with this situation. She clearly has feelings for Mr. Rochester, feelings that developed innocently as she was unaware of the wife-in-the-attic situation. Nevertheless, she knows, in her heart of hearts, that this is wrong. Further, she comprehends that the esteem that Mr. Rochester holds her in, arising out of her virtuousness, would be destroyed in agreeing to his proposal. She can either be virtuous or be loved — obey God or man — and not both.

While it is important, then, to distinguish between what is good and what is conventional, just because something is conventional does not mean that it is not good: lots of things are normal and expected because they are, in fact, good and proper things to do.

And so Jane flees. She flies into the night and nearly dies from exposure, is utterly worn down to her lowest, most pitiable state. Soon, Jane receives another offer of marriage in direct contrast with Rochester’s. A minister who has taken her in wants to marry her and take her with him as a missionary to India. However, he explicitly explains that he does not love her, in this infamous and blood-curdling line:

“God and nature intended you for a missionary’s wife. It is not personal but mental endowments they have given you; you are formed for labor, not love. A missionary’s wife you must — shall be. You shall be mine; I claim you — not for my pleasure, but for my Sovereign’s service.”

Jane struggles mightily with this, though ultimately decides — correctly — that it is against the nature of marriage to marry for utility, even (or, perhaps, especially) utility dressed up in pious-seeming words. Adam’s words at the creation of Eve were not “tool of my tools” but “bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh” (Genesis 2: 23).

And so Jane flees again, this time from a union that would have been very conventional, would have had all the outward appearance of good, and none of the substance. Jane decides to return to Mr. Rochester’s estate, having been unable to contact any of her former friends there and growing increasingly concerned about his welfare.

Upon arriving, she learns that Mr. Rochester’s wife, in a fit of rage, escaped into the house and lit it on fire, attempting to murder her husband and everyone else inside. Mr. Rochester, attempting to coax her down from the roof from which she would throw herself, was blinded and maimed in this final attempt to protect his wife. Jane reunites with Mr. Rochester, who is much chastened by the whole experience, and he repents memorably (in words which are, notably, absent from film and television adaptations of this novel):

“Jane! you think me, I daresay, an irreligious dog: but my heart swells with gratitude to the beneficent God of this earth just now. He sees not as man sees, but far clearer: judges not as man judges, but far more wisely. I did wrong: I would have sullied my innocent flower — breathed guilt on its purity: the Omnipotent snatched it from me. I, in my stiff-necked rebellion, almost cursed the dispensation: instead of bending to the decree, I defied it. Divine justice pursued its course; disasters came thick on me: I was forced to pass through the valley of the shadow of death. … Of late, Jane — only — only of late — I began to see and acknowledge the hand of God in my doom. I began to experience remorse, repentance; the wish for reconcilement to my Maker. I began sometimes to pray: very brief prayers they were, but very sincere.”

They reconcile, and the final chapter begins with Jane famously and succinctly declaring, “Reader, I married him.”

It appears that Jane Eyre takes up a common literary trope, showing how a virtuous woman can draw a man towards greater virtue within God’s gift of marriage. But it seems to me that there is something else going on, too. I think that Charlotte Brontë wants us to think about the difference between things that are good and things that look good.

Mr. Rochester is far from an ideal husband, at least for the majority of the book. He is a sinner, regardless of what sympathy we can offer to him in his convoluted and pitiable circumstances. But, ultimately, it is Rochester, the chief sinner of the novel, and Jane, the wrongfully accused scapegoat, who seek redemption from God and reconciliation with neighbor. The many better-behaved characters in the book — all of whom put a great emphasis on the fact that they are Christians — do not. It is this scandal at the heart of the novel, so often misinterpreted, that is the key to the entire book.

Christ’s parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector in Luke 18:9–14 is scandalous. The Pharisee was a highly respected religious leader, a pillar of his community, who likely did very public good works and worked to uphold morality (or, at least, convention). The tax collector was a traitor, a thief, a government shill, squeezing his neighbors and family members for cash to fuel decadence and war — but not before skimming some off the top for himself. The Pharisee looked like the good and moral person beloved by God, and the tax collector looked like the outcast hated on earth and in heaven. But Charlotte Brontë warns us, “appearance should not be mistaken for truth; narrow human doctrines, that only tend to elate and magnify a few, should not be substituted for the world-redeeming creed of Christ.”

Just like in Jesus’s parable, the self-assured, self-righteous characters in Jane Eyre who use their reputations and moral-sounding language to justify sin are not acting in moral, God-pleasing, or Christian ways. The obvious sinners in search of repentance, however, are. It is perfectly fine to admit this, Brontë argues, because attacking false virtue is not the same as assailing the real thing: “To pluck the mask from the face of the Pharisee, is not to lift an impious hand to the Crown of Thorns.” Instead, the lowliest, most despised characters — a friendless orphan and a disgraced gentleman who has lost his health, wealth and reputation — repent and turn to Christ. In doing so, they bring shame upon the proud and are themselves lifted up, a very biblical turn of events indeed.

C. S. Lewis remarked on the problem that occurred when, in English, the words “gentleman” and “Christian” started to become synonyms for “nice” or “wholesome.” Perhaps Charlotte Brontë wants us to consider something along those same lines in her novel: namely, “that likewise joy shall be in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons, which need no repentance” (Luke 15:7 KJV).

Jane Eyre is my all-time favorite novel, and it has always saddened me that the Christian content is never included in the film adaptations. Thank you for a wonderful and insightful article!

I read and enjoyed Jane Eyre just a few years ago. I really appreciate this literary reflection. Thank you for this series!

One of my favorite books. Thank you for calling out the ministers, they always made me so mad.

Always my favorite.

I know some don’t like Jane Eyre as much as Jane Austen, but I did. I liked the depth and the originality of it, and I like your analysis of it. Thank you for your thoughtfulness and sharing it with us.

It’s been years since I’ve read Jane Eyre. I’m going to re-read it with a new, more enlightened perspective. I look forward to the future articles in this series. Thank you!

oh, I’ve been saying this for years about this marvelous book that captured me when my mom gave me her own copy in my early teens. I’ve read it more times then

than i can remember & often quote Jane’s things when she decides to follow God’s ways, come what may. the

thanks so so much for writing this, i am invigorated to continue my quest 🙂