An art reflection by Robert Kolb on Lukas Cranach's "Law and Gospel." This is the first installment of a new monthly series providing reflections on works of art and music from a Lutheran perspective.

Martin Luther called justification the “article [on which] stands all that we teach and practice.” The teaching “that Jesus Christ our Lord and God, ‘was handed over to death for our trespasses and was raised for our justification’” (SA II 1) was at the heart of the Reformation.

While Luther proclaimed this doctrine of justification in words, one great Reformation artist brought out this theology visually. Lukas Cranach, the court artist in Wittenberg during Luther’s career there, dramatically depicted Luther’s teaching through his workshop’s altar paintings and woodcuts for books.

Lukas Cranach had established himself as an influential counselor of Elector Frederick the Wise and as a rising young German artist by the time Luther arrived in Wittenberg for the first time in 1508/1509. The preaching of the young Augustinian Brother who settled into life-long teaching duties in Wittenberg in 1511 quickly made a profound impression on the artist.[1] Their conversations probed the depths of Luther’s study of Holy Scripture and of the possibilities of expressing his teaching in visual forms.[2]

The symbolism in Cranach’s “Law and Gospel”

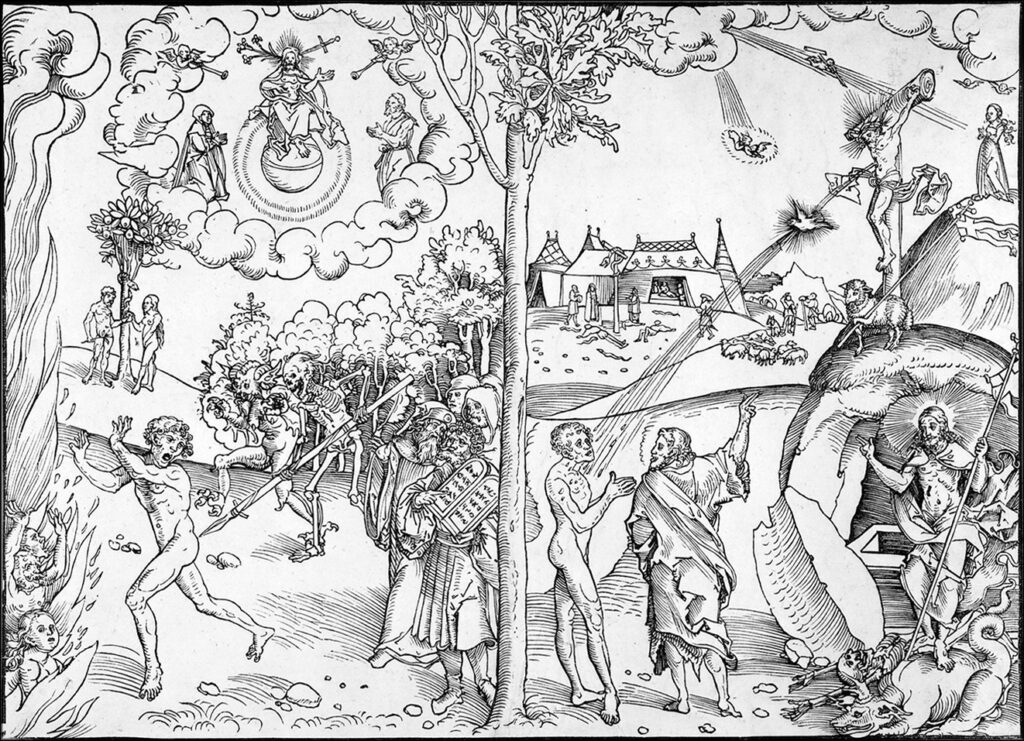

In a 1530 woodcut, Cranach depicted a vital element of Luther’s proclamation of the Gospel through his art: the distinction of “Law and Gospel.”

With one picture, Cranach places what Luther taught vividly before our eyes: the heart of the Good News of the salvation of sinners.

Cranach’s Law/Gospel motif appeared in altar pieces and woodcuts for publications, both treatises and single sheets. It follows in the tradition of the medieval “Bibles of the poor” [Biblia pauperum], illustrations of basic Biblical stories or themes that summarized the instruction of the faithful. Variations in the elements presented in the Law/Gospel illustrations supplement the motif’s standard components.

The two panels depict Luther’s axiom that the subject of theology, of all biblical proclamation, focuses on the guilty sinner and the forgiving God. The left-hand panel depicts the biblical background of the Fall and the oppression of the devil, death and the Law that hounds the sinner toward the flames of hell. The right-hand panel depicts the crucified and rising Christ with triumphant Lamb standing on death and the devil. The facial expressions of terror and of wonder on the sinner’s face in the panels reflect the reactions Luther had experienced to God’s addressing him.

Dividing the two panels is a tree, with dead branches on the side of the Law and live branches on the side of the Gospel. The subject matter is set against a medieval German background (in the painting) with castle towering over a town with church towers in the midst of typical contemporary buildings. Cranach thereby emphasized that the message that comes out of the historical events of the past address his own contemporaries with God’s call for repentance and His gift of liberation from sin, death and the devil.

At the top of the left panel sits Christ the judge, with sword and lily, typical of medieval depictions of the Lord coming on the Last Day, indicating His wrath and mercy. Adam and Eve, with serpent in the fruit tree, are disregarding God’s Word and following Satan’s advice. In some versions of this woodcut, the incident of Israel’s receiving judgment through fiery serpents (Num. 21:4–9) appears in the left panel as a sign of God’s punishment of sin — in others it appears in the right panel, accentuating the grace of God as the bronze serpent on the cross offers deliverance to the faithful.

The Gospel panel on the right contains an angel. He is sometimes coming to Mary to announce the birth of her child Jesus and sometimes descending to the shepherds, also to announce the Savior’s birth. The dramatic resurrection of Christ towers over His hanging on the cross as the commanding conclusion of the eye’s moving across the illustration. The lamb has devil and death underfoot, and the condemnation of the Law has disappeared. John the Baptist stands in for contemporary preachers of the Gospel, pointing the sinner to the crucified and risen Lord.

The texts of Cranach’s “Law and Gospel” panels

Pictures are, of course, not worth a thousand words, for interpreting what we see depends on what we have stored away in our mental programming. In the case of God’s engagement with His human creatures throughout history, the Creator addresses us with words. What He has said lays the basis for how we understand and interpret what we see. Depictions have the potential of conveying multiple and sometimes contradictory impressions. Therefore, Cranach accompanied his portrayal of sinners and their deliverance from sin and death with Bible verses.

In some renderings of the motif, the words of Romans 1:18 proclaim, “the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and human wickedness” above the left panel. The Gospel panel’s message is summarized with the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14, “the Lord himself will give you a sign. Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son.”

In three frames under the left panel, Bible verses explain or apply elements in the panel. The first, on God’s judgment, cites Romans 1:18: “God’s wrath is revealed from heaven over all those who live godlessly and unrighteously,” and Romans 3:23 and 27, “we are all sinners and fall short of the standing that they are to have before God, so that we are not able to boast before God.” The second frame explains “the devil and death” with 1 Corinthians 15:56: “sin is the spear of death, the power of sin is the law,” and Romans 4:15, “the law delivers wrath.” “On Moses and the Prophets,” the third frame, reminds viewers, with Romans 3:20, that “through the law comes the knowledge of sin,” and Matthew 11:13, “the law and the prophets are valid up to the time of John.”

The explanation of the right panel begins with comment on the human being: “the righteous live by his faith” (Rom. 1:17) and “We hold that a person is righteous through without the works of the law” (Rom. 3:28). “On the Baptizer” reminded readers of John’s proclamation, “Behold, that is God’s Lamb that takes away the sin of the world,” (John 1:29). Also quoted is 1 Peter 1:2, which addresses those who are elect “in the sanctification of the Spirit for obedience and sprinkling of the blood of Jesus Christ.”

The final frame on “Death and the Lamb” reminds readers that “death is swallowed up in victory. Death, where is your spear? Hell, where is your victory?” (1 Cor. 15:54–55).

The Wittenberg reformers created and composed the many tools for spreading the Gospel of justification by faith alone. Cranach’s illustration of the central concepts that bring people of all ages to repentance and to faith in the crucified and risen Christ, Jesus the Savior, stands as a monument to his theological insight and aptitude. His witness joins the proclamation we find in the writings of Luther, Melanchthon and their theologian colleagues, calling sinners still in the twenty-first century to the cross and empty tomb of our Lord and Deliverer, Jesus Christ.

[1] Many conversations on Scripture and on daily life formed a firm friendship between Cranach and Luther. When Cranach and his wife received word of the death of their oldest son while he was studying artistic technique in Italy, Luther sped to their home to give them comfort.

[2] In addition to creating altar pieces and woodcuts for Luther’s catechisms and Bible translation, Cranach’s business savvy aided other printers in developing Luther’s “brand.” Cranach designed a title page with several innovations — attractive frames or illustrations alongside the name of the author and the place of publication, Wittenberg — that caught the eye and thus the customer, increasing the sales of Luther’s printed works. (See Andrew Pettigree, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation [New York: Penguin, 2015]).