C.F.W. Walther

A.D. 1811–1886

Faced with false confession or schism, he chose the hard path, navigated extreme challenges, and helped establish our church body.

In this series, Lutheran historian Molly Lackey will trace the history of the church, from the time of the apostles through the twentieth century. As the Body of Christ, our history transcends time, country and citizenship: “God’s Word is our great heritage.”

Imagine you’re a German Lutheran immigrant making your new home in Perry County, Missouri. Ever since your arrival in America five months ago, you’ve had a hard time: You thought that coming to America would allow you to worship according to the demands of your conscience, as a Lutheran, instead of the demands of the state, which was forcing your Lutheran church to join with the Reformed. But that lofty goal is harder to focus on in your new life of eating “by the sweat of your brow” — which, so far, has meant barely eating at all. You’re destitute, the cabins and tents you live in aren’t nearly sturdy enough, and people keep getting sick, even dying.

It was bad enough, but now rumors are circulating about the bishop of your community, the leader of you Saxon immigrants, Martin Stephan. Everyone is saying that Stephan has been sinning grossly behind everyone’s backs, but nobody knows what to do. Now you’re in front of Carl Ferdinand’s door, the young clergyman who was your pastor back in Germany — the one who convinced you to join Stephan’s immigrating group. You go to knock, but your hand waivers. What if what they’re saying is true? If you lose your bishop, what will become of the settlement and your new church? What will become of you — and your hopes to worship as Lutherans should?

From German pastor’s son to confessional Lutheran immigrant

Carl Ferdinand Wilhelm Walther, called “Ferdinand” by his family and C.F.W. by us today, was born on Oct. 25, 1811, in Saxony, Germany. He was a pastor’s son and went on to become a pastor himself. He was studying theology at the University of Leipzig when, at 18 years old, he nearly died of an illness affecting his lungs. While he recuperated, he read through the works of Martin Luther with a vengeance. It was because of this experience that C.F.W. Walther became committed to confessional Lutheranism: believing and practicing as a Lutheran who holds to all of the writings contained in the 1580 Book of Concord.

By the time Walther was ordained at age 26 in 1837, his confessional Lutheranism was already becoming a bit of a problem. The Saxon government decided to take a cue from the larger and rapidly-growing Prussians, who 20 years earlier had enacted the Prussian Union, which merged the Lutheran and Reformed (Calvinist) churches in order to centralize the state church and consolidate power. Because Lutherans and the Reformed hold very different doctrines on major points like the Lord’s Supper, the result was that the Prussian state forced Lutherans to accommodate Calvinist teachings, which went against Lutheran confessional documents. This in turn led to state-sponsored persecution of so-called “Old Lutherans,” who defied the state by worshipping in secret.

Saxony, where Walther lived, did not go as far as Prussia, but it still tried to wield authority over church teachings, suppressing confessional Lutheran thought in favor of rationalism. Rationalism, in Walther’s day, was a strain of thought which grounded Christian doctrine in what made sense to human logic, rather than Scripture’s testimony. Taken to an extreme, this led the kind of preaching that Walther heard as a young man, with pastors exhorting hearers to good hygiene and new agricultural methods from the pulpit.

Walther was so disheartened by the preaching and teaching of his day that he ended up joining — and encouraging others to join — a group of 707 Saxon Lutherans leaving Germany for America and the promise of freedom of worship. Five ships left Germany, but only four ships made it to America: the fifth, the Amalia, was lost, along with the 105 souls onboard and all its cargo. The 602 who survived the four-month sea journey landed in New Orleans in January 1839 and made their way to St. Louis. Most of the group left St. Louis for Perry County, though 120 remained and founded historic Trinity Lutheran Church in St. Louis.

Shepherding the scattered sheep

Things in Perry County soon became dire. Though plans were in place to build a “bishop’s palace” for their leader Martin Stephan, most of the group was suffering greatly from want of food, shelter and medical attention. Public opinion was already turning against Stephan when rumors, then formal charges, of immorality, misadministration of funds, and false doctrine were brought against him, on which grounds he was formally deposed on May 30, 1839.

Stephan’s expulsion, unsurprisingly, only increased the anxiety felt by the already beaten-down Saxon immigrants. Tensions came to a head at the Altenburg Debate in April 1841. Many thought that the hardships they faced were a sign from God that they had sinned by leaving behind their churches in Germany, and that their new church in Missouri was not a valid one. C. F. W. Walther convinced his fellow Saxons that the difficulties and sin-caused hurts they suffered were not God’s judgment, but rather were the actions of a sinful person and the effects of living in a fallen world, which should not be interpreted as invalidating this new church. Ultimately it was God, not man, who established His church on earth, and no action of man would prevail against it.

C. F. W. Walther would go on to become the first president of Concordia Seminary and the first president of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod when it was founded six years later in 1847. He wrote, taught, and preached prodigiously, and lived a very full and productive life until his death on May 7, 1887. His life was hard, but Walther’s steadfast grip on God’s Word and his unwavering commitment to its expression in the Lutheran Confessions has shaped the Synod he helped to found for over 175 years.

Editor’s Note: The next installment of this series, on Rosa Young, a great figure in Southern Lutheranism, will be posted two weeks from today. Check back then or follow us on social media to catch it!

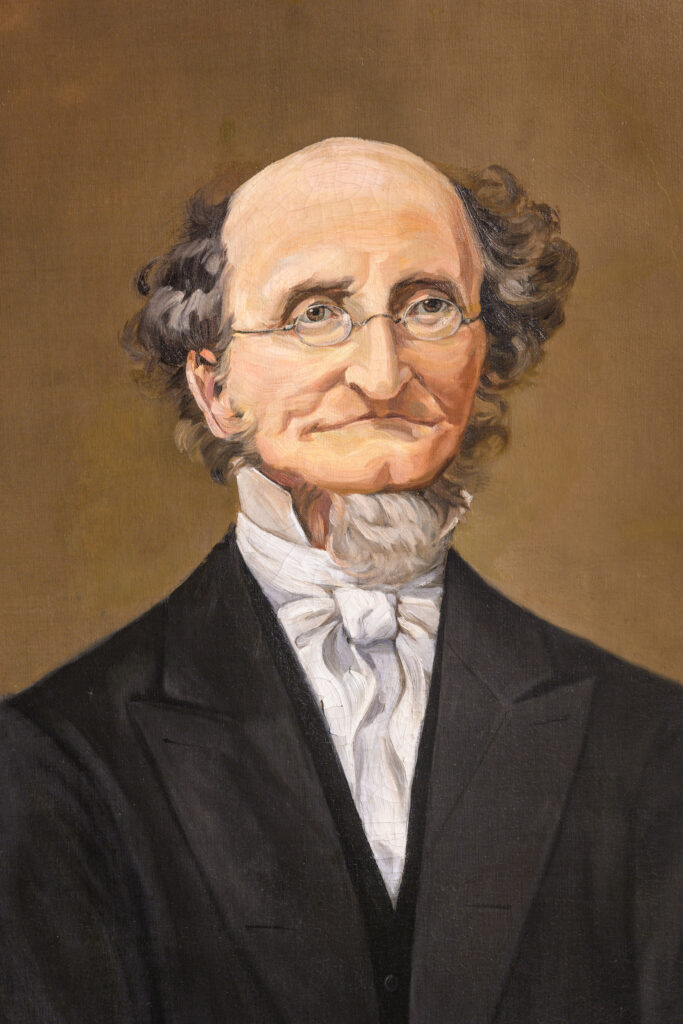

Image: Reproduction photograph of a painting depicting C. F. W. Walther at the International Center of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. Photo by LCMS Communications/Erik M. Lunsford.