Thomas Aquinas

A.D. 1225–1274

A diligent scholar, Aquinas sought to know God’s truth and communicate it in a clear way to a confused world.

In this series, Lutheran historian Molly Lackey will trace the history of the church, from the time of the apostles through the twentieth century. As the Body of Christ, our history transcends time, country and citizenship: “God’s Word is our great heritage.”

Imagine you are a Dominican scribe, working to write down and collect the works of your fellow monks. You are in a good mood today, because you will be working with one of your friends. You knock at his cell door. No reply. Well, he’s probably still eating breakfast — the great ox-like Thomas Aquinas was never one to leave a meal early. Several minutes pass, but he never comes. You knock again, and the door swings open. You enter and start getting out your quill, inks and vellum, but your brother monk shakes his head quietly. You ask if he is unwell — you’d noticed he was acting strange at Mass that morning — to which he replies no. He is finished. He will write no more. You plead with him to no avail. “I cannot,” says Thomas, “because all that I have written seems like straw to me.”

Tommaso d’Aquino, known to us English-speakers as Thomas Aquinas, was born into a wealthy and powerful Sicilian family. While the rest of his brothers prepared for prestigious military careers, Thomas was educated with the intention of his becoming an abbot. The family’s well-laid plans were shattered, however, when the 19-year-old Thomas announced he was becoming a Dominican friar and had no ambitions for authority, even within the church. The Aquino family responded by kidnapping Thomas and trying to force him to change his mind and pursue ecclesiastical power, but he refused and eventually escaped.

Aquinas was educated in Paris, where his classmates derided him for being quiet, reserved and, they assumed, dim-witted. His professor, the famous scholar Albertus Magnus, is said to have declared to the class, “You call him the dumb ox, but in his teaching he will one day produce such a bellowing that it will be heard throughout the world.” His teacher was correct; the slow and methodical Thomas became a tutor and teacher himself, taking on a significant role in the theological debates of his day.

From quiet student to prolific theologian

Thomas Aquinas’s monumental theological and philosophical output spanned almost every conceivable topic, despite the fact that he died at only 48 or 49 years old. His most famous is the Summa Theologica, or “Summary of Theology,” a comprehensive outline of Roman Catholic doctrine. The format of the Summa — an argument given in the form of possible objections, each of which receives its own response — is drawn from Aristotle’s writings, which Aquinas used in service of theology.

The role of Aristotle within the Christian church was a hot-button topic in Aquinas’s day. Many of the early Christians — including Augustine — were heavily influenced by Aristotle’s teacher Plato. The two philosophers did not agree, and, as a result, there was an anti-Aristotle bias among Christian thinkers for centuries. Plato taught that the physical world was a dim shadow of the spiritual world (or the world of Forms or Ideas). Aristotle, on the other hand, taught that the physical world and our perceptions of it were a legitimate source of information. Where Plato was transcendental, Aristotle was common-sense.

Aquinas believed that Aristotle could be brought into alignment with Christian teaching in order to better understand God, man, and man’s place in the world. For example, Aquinas re-introduced Aristotle’s idea of everything having four causes, or ways of explaining or describing something: what the thing is made of (material cause), what it is shaped or looks like (formal cause), how it was created (efficient cause), and why it was made (final cause). Although this is not from the Bible — it’s philosophy, not theology — it can be a very helpful way of talking about complicated topics, theological or otherwise.

Baptizing an ancient philosophy

Aquinas did not want to make Christianity more Aristotelian; he wanted to make Aristotelianism Christian. Unfortunately, problems still arose from Aquinas’s attempt to baptize this pagan philosophical framework, both during his life and after. Aquinas cemented the concept of transubstantiation into Roman Catholic dogma. Transubstantiation is the belief that the “substance” (an Aristotelian category) of the bread and wine in the Lord’s Supper is transformed (changed) into the body and blood of Christ, while the “accidents” (or appearance — another Aristotelian category) of bread and wine remain. In this view, only two things are present in the Lord’s Supper — Christ’s body and blood. During the Reformation, Martin Luther would argue that transubstantiation was a philosophical explanation rather than a scriptural one, and so could not be enforced as doctrine. The Bible does not speak in Aristotelian terms about “substance” or “accidents.” Instead, the Bible states that Christ’s body and blood are truly present in, with and under the bread and wine. Thus four things are present in the Lord’s Supper: Christ’s body and blood, and bread and wine.

Even in Aquinas’s own lifetime, the return of Aristotle brought with it problems. There were other theologians who were importing bits of Aristotle’s philosophy that were directly at odds with the Bible — teaching, for example, that the world had always existed and was uncreated. Aquinas debated these teachers, but found the situation extremely upsetting. A few years later, Aquinas experienced something while celebrating the Mass, the exact nature of which he never shared. Whatever it was, it brought about a great change: He never wrote again. The Summa Theologica is, in fact, unfinished as a result. Three months later, Aquinas was dead.

Thomas Aquinas’s theological and philosophical work continue to be the basis of much official Roman Catholic teaching. In fact, Thomas Aquinas forever changed the study of theology throughout Christendom. Although Luther rejected how Aquinas (and many other medieval scholars) approached theology, other Lutheran scholars, even Philipp Melanchthon, used Aristotelean frameworks in order to write more clearly about challenging theological topics.

While Lutherans acknowledge the limits of philosophy to understand our transcendent God, we can still find encouragement in Thomas Aquinas’s firm belief in God’s gift of a knowable and good created world. We join Aquinas in the words of his communion hymn, Adore Te Devote, “Thee We Adore, O Hidden Savior” (LSB 640, v. 5):

O Christ, whom now beneath a veil we see, May what we thirst for soon our portion be: To gaze on Thee unveiled and see Thy face, The vision of Thy glory, and Thy grace.

Editor’s Note: The next installment of this series, on the great reformer Martin Luther, will be posted two weeks from today. Check back then or follow us on social media to catch it!

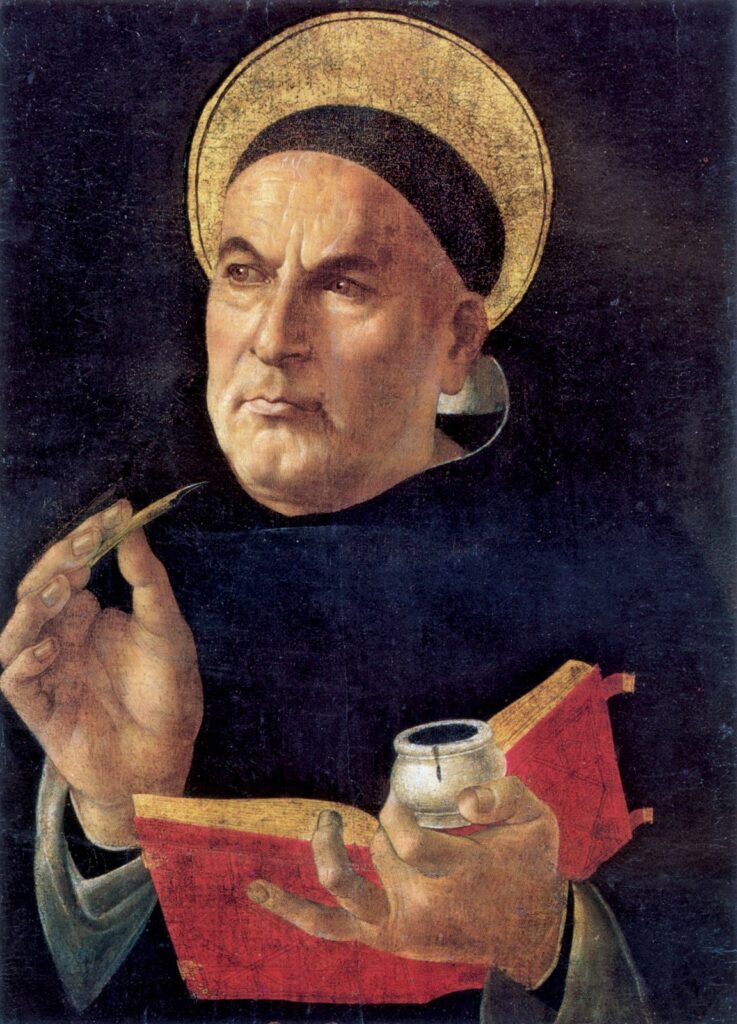

Image: “Thomas Aquinas,” Sandro Botticelli, 1460–1510.