Paul the Apostle

c. A.D. 5–64

Once a persecutor of the church, he was called by Christ to share His Good News with the Gentiles — and, down the centuries, with us.

In this series, Lutheran historian Molly Lackey will trace the history of the church, from the time of the apostles through the twentieth century. As the Body of Christ, our history transcends time, country and citizenship: “God’s Word is our great heritage.”

Imagine you’re an early Christian, a really early Christian. You saw Christ with your own eyes or personally know somebody who did, and you have taken the hard road of discipleship and are following Him. You’ve heard about persecution — maybe you even saw Stephen being stoned to death! You are facing the confusion, disappointment and disgust of friends, family members and neighbors for following this newfangled superstition. One day, you arrive at church and see a familiar face, but you can’t quite place him. Someone announces that this is Paul, a preacher and missionary of Christ, who is visiting your church — and then it hits you: This was Saul, persecutor of Christians.

St. Paul was born Saul, a Jew in the tribe of Benjamin and a Roman citizen of the city Tarsus in the Roman province of Cilicia, in modern-day Turkey, sometime between 5 and 10 A.D. Saul wasn’t a slacker when it came to his beliefs and practices. Saul was the real deal — and that put him at odds with Christ and His church.

From Christ’s persecutor to Christ’s apostle

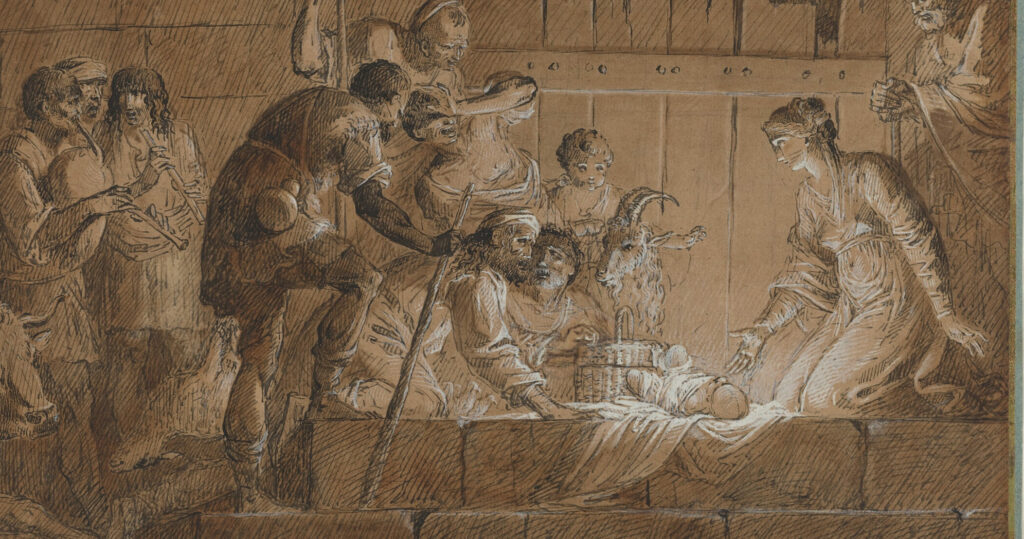

The first time we hear about Saul is at the death of St. Stephen, the first martyr, sometime around 34–36 A.D. Stephen had been debating with a number of Jews, including, perhaps, Paul: Scripture says that Stephen disputed with “those from Cilicia and Asia” (Acts 6:9). They had Stephen seized and taken to the Sanhedrin to be tried for blasphemy. After Stephen gave a profound account of Christ’s fulfillment of the Pentateuch, the council began stoning him — an event at which Saul was present: “the witnesses laid down their garments at the feet of a young man named Saul” (7:58). In fact, “Saul approved of his execution” (8:1) and went on to severely persecute the church (8:3).

But as we know, Saul turned from his persecution of Christians. Indeed, he converted to Christianity, as recounted in Acts 9:1–19. Saul, “still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord,” was on his way to Damascus. He was looking for Christians in the synagogues there. He intended to capture them and bring them to Jerusalem, presumably for trial and execution like Stephen. But outside of the city, he was overwhelmed by a great light and the voice of Christ pleading, “Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting me?” Christ directed him to enter the city, despite his now being blinded. (It’s worth noting that neither here, nor elsewhere, does Jesus rename Saul as “Paul.” The book of Acts switches from calling him Saul to calling him Paul at Acts 13:9. Many Jews had a Hebrew and a Greek or Latin name — “Paul” is derived from the Latin paulus, meaning small.)

Meanwhile, the Lord also appeared in a vision to a Christian named Ananias and told him to find Saul. Ananias was unsure — he’d heard bad things about this dread persecutor! But Jesus was insistent, saying, “Go, for he is a chosen instrument of mine to carry my name before the Gentiles and kings and the children of Israel. For I will show him how much he must suffer for the sake of my name.” Ananias found Saul and laid hands on him to heal him of his blindness — and Paul immediately rose and was baptized.

Spreading the Gospel near and far

Paul proclaimed the Gospel in the synagogues of Damascus and Jerusalem. However, his sudden, public conversion obviously attracted the ire of his former coconspirators, who wanted to put him to death. So Paul was sent to Tarsus for his own safety, where he remained until around 46 A.D. Then he and the missionary Barnabas went to Antioch, where they taught for a year. They then returned to Jerusalem in order to bring aid to Christians suffering because of a famine (Acts 11:25–30).

From there, Paul embarked on his first missionary journey to the Gentiles in Cyprus and Galatia. Paul would go on to travel across Southeastern Europe and the Near East, to Greece, Ephesus, Corinth, Jerusalem and Rome, though he first shipwrecked at Malta. In addition to this travel and missionary work, Paul also was involved in the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15, where he and Barnabas debated with the other apostles, arguing that Gentile converts to Christianity were not required to obey Jewish ceremonial laws and customs, like dietary restrictions or circumcision. Christians were saved by Jesus, Paul argued, not by keeping the Law.

On top of this busy itinerary, Paul was a prolific author of epistles, letters to young churches around the Mediterranean. The dating of Paul’s letters is unclear, though scholars generally believe Galatians or 1 Thessalonians to be his earliest. Certain scholars (like those who left the LCMS’s Concordia Seminary during the Walkout) claim Paul did not write all of these letters — and even outright reject some of his teachings. Regardless of shifting academic winds, we continue to confess the authorship, inerrancy and authority of Paul’s writings, writings that brought great clarity of doctrine and comfort of conscience 1500 years later to Martin Luther, and continue to do so for many more today.

Paul frequently found himself in prison for his faith. When Paul arrived in Rome around 60 A.D., he was placed under house arrest (Acts 28:16). Scripture does not elaborate on what happened next, but Clement of Rome, a contemporary of Paul’s, and other early church writers say that Paul was martyred. Because Paul was a Roman citizen (see Acts 23:27), he would have been beheaded, the only legal (and most humane) form of execution for Roman citizens. The infamous Nero, persecutor of Christians, is the Caesar to whom Paul appealed in Acts 25:1–12, and the early church historian Eusebius writes that Paul was executed during Nero’s persecution of Christians following the Great Fire of Rome, likely around 64 A.D. The story of St. Paul begins with the death of a Christian and ends with one, too. Saul, persecutor of Christians, became St. Paul, who brought the Gospel to the Gentile world, meaning, indirectly, to most of us modern-day Lutherans.

Editor’s Note: The next installment of this series, on the martyrs Perpetua and Felicitas, will be posted two weeks from today. Check back then or follow us on social media to catch it!

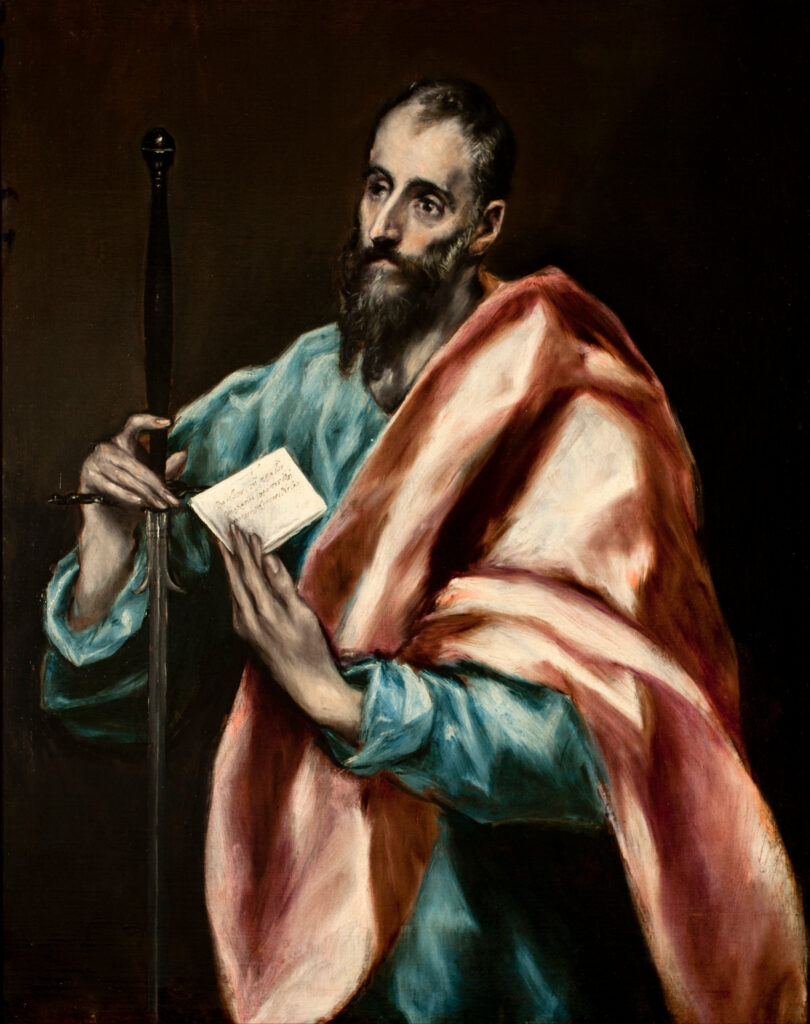

Image: El Greco, “St. Paul,” 1610–14.

I regard Paul as a supreme example of how God redeems by turning his enemies into his instruments. To receive forgiveness is to receive a blessed calling. As we aspire to fulfill freely and gratefully the purposes in this life for which God has shown mercy and still gives his gifts, we bring glory to God and walk with greater hope and joy.

Christ “died for all, that those who live might no longer live for themselves but for him who for their sake died and was raised” (2 Cor. 5:15 ESV).