By Robert W. Paul and Heather Smith

LCMS schools represent the largest non-Catholic, single denomination school system in the United States. Generations of teachers and students have received Lutheran educations and, through the Synod’s college and university system, been trained as Lutheran educators. As the school year begins again in our LCMS schools, homeschools, colleges and universities, a pair of veteran Lutheran educators (pastor/headmaster Robert Paul and former teacher Heather Smith) tell the story of Lutheran education and show how God’s Word has continued to shape the work of Lutheran teachers and students over the past 500 years.

What Is Lutheran Education?

The past several centuries offer a varied picture of what we today call “Lutheran education.” It’s a picture influenced not only by Reformation theology but also by government mandates and standards, evolving educational theory and massive cultural shifts. Given this, we might well ask: What is Lutheran education? What makes “Lutheran education” Lutheran? In an age of many educational options, why should members of the LCMS support their congregation’s or region’s LCMS schools? To find meaningful and significant answers to these questions, we look to our history, our Lutheran Confessions and, ultimately, the Scriptures.

The history of Lutheran education from Luther to Walther to the present day indicates that the first test of whether a school is Lutheran must be a theological one: Does a Lutheran school, first and foremost, teach the prophetic and apostolic Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments? Do its faculty members abide by the Lutheran Confessions and teach according to them? Is justification (according to Romans, Galatians and the Augsburg Confession) taught as the central truth of the Scriptures? Lutheran identity must begin with Lutheran theology.

With a theological foundation built on the Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions, faculties and administrations can then carefully examine the curricula of their schools and how it is delivered to their students. Educational strategies may vary depending on the context — the first generations of LCMS schools had understandable diversity in their curricula and practices, and there continue to be many different ways in which Lutherans are educated in the LCMS. Ultimately, however, the educational philosophies and practices of LCMS schools must be based in the same Scriptures and Confessions. Lutheran doctrine and identity are what should unite pastors, teachers, administrators, professors, parents and students.

God has blessed Lutheran education over the last two centuries in this country, through challenges and successes. Schools open and close. Enrollment declines and grows. Teachers are commissioned and retire. Children are baptized and confirmed. Faculty and staff grow in their knowledge of the Scriptures and the Confessions and learn to teach students faithfully and diligently.

There are and always will be reasons for Lutheran Christians to lament the state of education in our Synod. The devil, the world and our sinful flesh do not want us to hallow God’s name or let His kingdom come, and Lutheran education fosters communities where God’s name is hallowed, His kingdom comes and His will is done.

What differentiates Lutheran education from all other educations available to us? The Gospel of Jesus Christ — the forgiveness of sins freely given for the life of the world, distributed through the Word and the Sacraments. All true Lutheran education flows from and is built upon this truth of justification. It frames the curricula, the administration and the day-to-day life of the school. Just as the Gospel of Jesus Christ substantially shaped the life of the church (as shown to us in the Gospels, Acts and the Epistles), so, too, does the Gospel of Jesus Christ substantially shape how we educate the next generation of Christians.

Five hundred years ago, Martin Luther wrote a letter to establish and maintain Christian schools in Germany. Today, the LCMS has the opportunity to further establish and maintain Christian schools in America. The task is fraught with challenges and opportunities. Many imagine education to be a means to an end, preparation for jobs and careers or even an obstacle to real progress and accomplishment in life. These arguments were lobbed at Luther and the Reformers too. Yet as long as the Lord Christ tarries, Lutherans will continue to stand firm on the Scriptures and Confessions and educate our children in the way they should go. For when we instruct our children in the “discipline and instruction of the Lord” (Eph. 6:4), they will not depart from it (Prov. 22:6). With the apostle Paul, Lutheran educators everywhere can continue to say with gusto: “If God is for us, who can be against us?” (Rom. 8:31).

Reformation Foundations

Although Martin Luther’s efforts during the Reformation centered around the Gospel truth of justification, he also recognized education of the young as essential to the church’s Gospel work and conscientiously laid the groundwork for what would become Lutheran education.

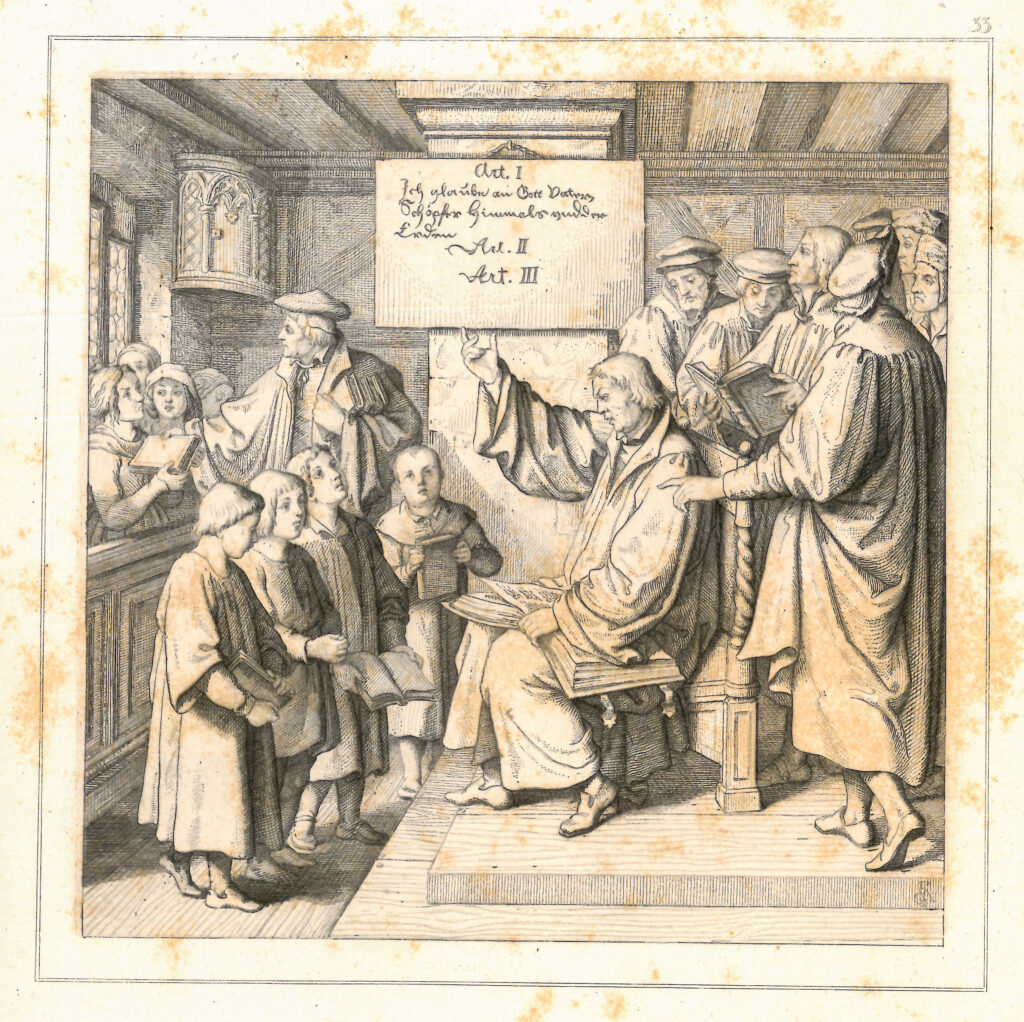

Luther the Educator: 1524–1546

Five hundred years ago, in early 1524, Martin Luther composed a letter “To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany That They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools.” In this treatise, Luther argued that Lutheran churches should also have schools that teach the faith to their children, citing Psalm 78: God “established a testimony in Jacob and appointed a law in Israel, which He commanded our fathers to teach to their children, that the next generation might know them, the children yet unborn, and arise and tell them to their children.” Luther also referenced the Fourth Commandment, wherein children are charged to obey their parents. Why? The Fourth Commandment does not merely teach what children should do for their parents, but it also teaches what mothers and fathers owe their children. Parents are to show their children the way they should go.

We can learn much from Luther on education. Many of his writings show him to be concerned not only about the purpose of education, but also about mundane details of scope and curriculum. He was critical of the Scholastic education he received as a youth and insisted instead that justification by faith in Christ be at the heart of all education, prescribing schools for young boys and girls that were grounded in the Holy Scriptures, the biblical languages and the “good books” of antiquity.

In the Latin edition of the Large Catechism, Luther concludes his discussion on the Fourth Commandment by saying,

Let everyone know, therefore, that it is his duty, on peril of losing the divine favor, to bring up his children above all things in the fear and knowledge of God, and if they are talented, to have them instructed and trained in a liberal education1, that men may be able to have their aid in government and in whatever is necessary.

Luther’s hyperbolic language, based in Ephesians 6, illustrates the sense of urgency and care that he wished to see given to education. Luther hoped that catechized children would be well trained to serve others through their vocations. Above all, he wanted Christians to bring up their children in the paideia (“instruction”) of the Lord, so that they would not depart from it.

A Reformation Priority: 1519–1600

This impetus did not die with Luther. The education of Christian youth was a matter of great significance to many other leading lights of the Reformation. Half of the contributors to the Book of Concord — Martin Luther, Philip Melanchthon, Martin Chemnitz and David Chytraeus — were directly involved in Lutheran education at the primary, secondary and university levels.

Melanchthon echoed Luther’s core principles in his educational reforms in Germany. Chytraeus, one of the authors of the Formula of Concord, reshaped education in the north of Germany along the same scriptural and classically minded lines. The “School Order of Brunswick,” authored by Chemnitz (another author of the Formula), laid out a similar education for all boys and girls. Lutheran theology begat a Lutheran education that taught the Scriptures, the languages of the Scriptures and the arts essential to Christian civilization. The Lutheran reformers cared deeply for the theology and the curricula of the schools that taught the young people in their care.

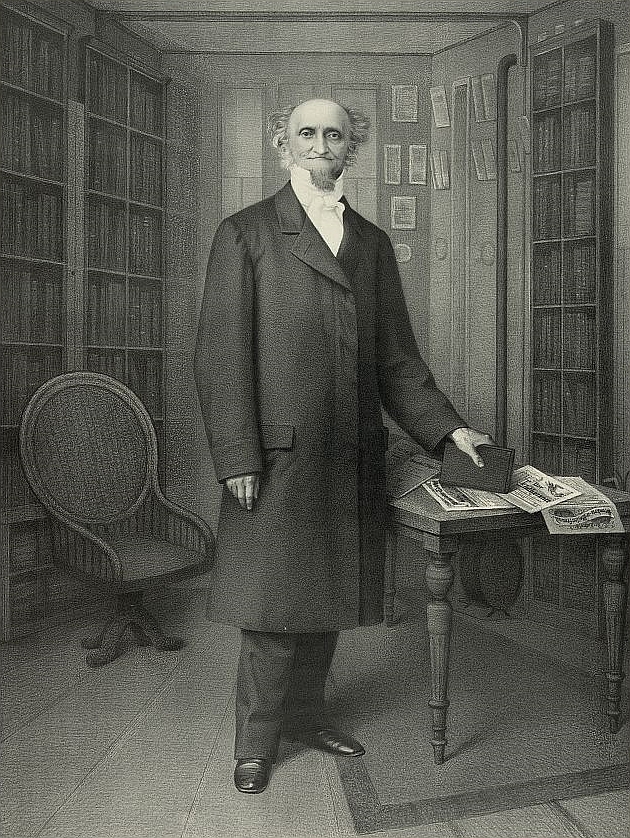

Walther, Pastor and Schoolteacher: 1837–1839

C.F.W. Walther began his ministry in the 19th century as pastor to a congregation and school in Saxony. He was particularly active in the school. Eventually, he involved himself not only in the pastoral teaching of theology and the catechism, but also in the secular subjects that belonged to the teacher. This brought him into conflict with the teacher and administrator of the school because Walther found theological issues in the non-theological textbooks. False teaching (rationalism) had infiltrated the textbooks given to the teachers and students.

Walther rightly recognized that theology and instruction in “non-theological” subjects go hand in hand. Like his 16th-century Lutheran ancestors, he saw education as a continuous whole, with both sacred and secular subjects subordinate to scriptural truth. Thomas Korcok (Lutheran Education — see “For Further Reading” below) suggests that education may have been one of the key reasons why the Saxons under Walther chose to emigrate to the United States in 1838.

Lutheran Education in America2

Throughout their remarkable 180-year history, our LCMS schools have suffered the devil’s blatant attacks and subtle cunning aimed at snatching Christ’s children from His church. Yet our Lord has graciously defended our schools.

Founding Lutheran Schools in America: 1838–1847

In 1838, five ships carrying over 700 German Lutherans set sail for America. These Saxon immigrants could not endure the secular rationalism their children were being taught in the German schools. They left their country largely to protect their children’s faith.

On the voyage, the school-aged children received daily lessons. Despite extreme poverty and hardships, one of the first things the settlers in Perry County, Mo., built was a log cabin schoolhouse.

They shared the conviction of C.F.W. Walther, who declared, “May God preserve for our German Lutheran Church the treasure of its parochial schools! Humanly speaking, everything depends on that for the future of our church in America” (Der Lutheraner XXIX, Feb. 15, 1873).

Walking Together in Education: 1847–1890

In the 1847 founding constitution of the LCMS, one of the requirements for membership was “Provision of a Christian education for the children of the congregations.” And, indeed, every one of the Synod’s founding congregations had a Christian day school.

The 1860s and 1870s saw a proliferation of textbooks for Lutheran schools from Concordia Publishing House (CPH).

Combatting the Allures of Modernism: 1890–1914

As material prosperity flourished in the 1890s, the church frequently sounded warning cries against the worldliness of the era. For the first time in their history, the Synod’s schools saw a decline in enrollment.

Yet despite this decline, Lutheran schools endured where others had failed. By 1890, most denominations’ parochial schools had died out. Along with the Lutherans, only the Roman Catholics, Dutch Reformed and Seventh-Day Adventists managed to maintain systems of Christian day schools.

Fighting for Survival: 1914–1935

With the eruption of World War I, LCMS churches and schools became the targets of violent hatred. In 1918, two Lutheran schools were burned by angry mobs and another was dynamited.

Laws requiring attendance at local public schools were pushed in some states. Advocates viewed parochial schools as a threat to American society and lobbied for the teaching of generic “Christian” religion in public schools, condemning church schools that clung to distinctive theological doctrines.

Meanwhile, drought, foreclosures and bank failures forced farm families to relocate to cities. Many rural, one-room schoolhouses (which still accounted for more than half the Synod’s schools) had to close.

Still, Lutheran schools strove to prove their worth. CPH published scores of English-language textbooks, and LCMS teachers’ colleges were quick to cooperate with new state requirements for teacher certification.

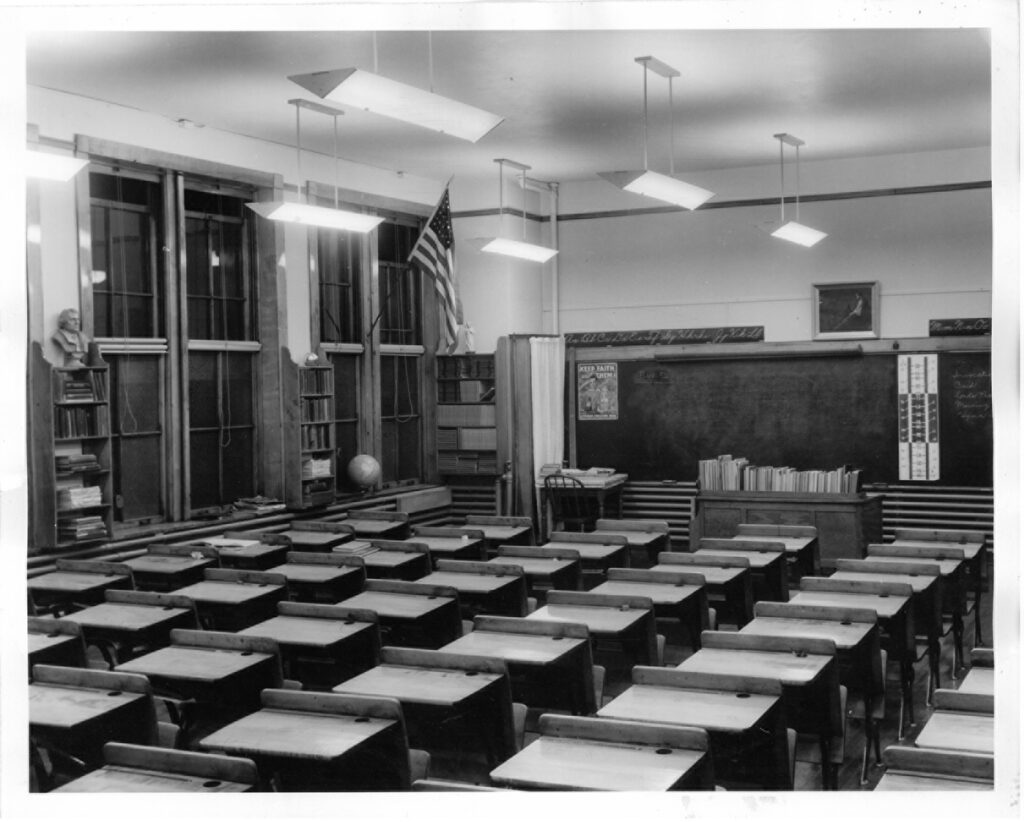

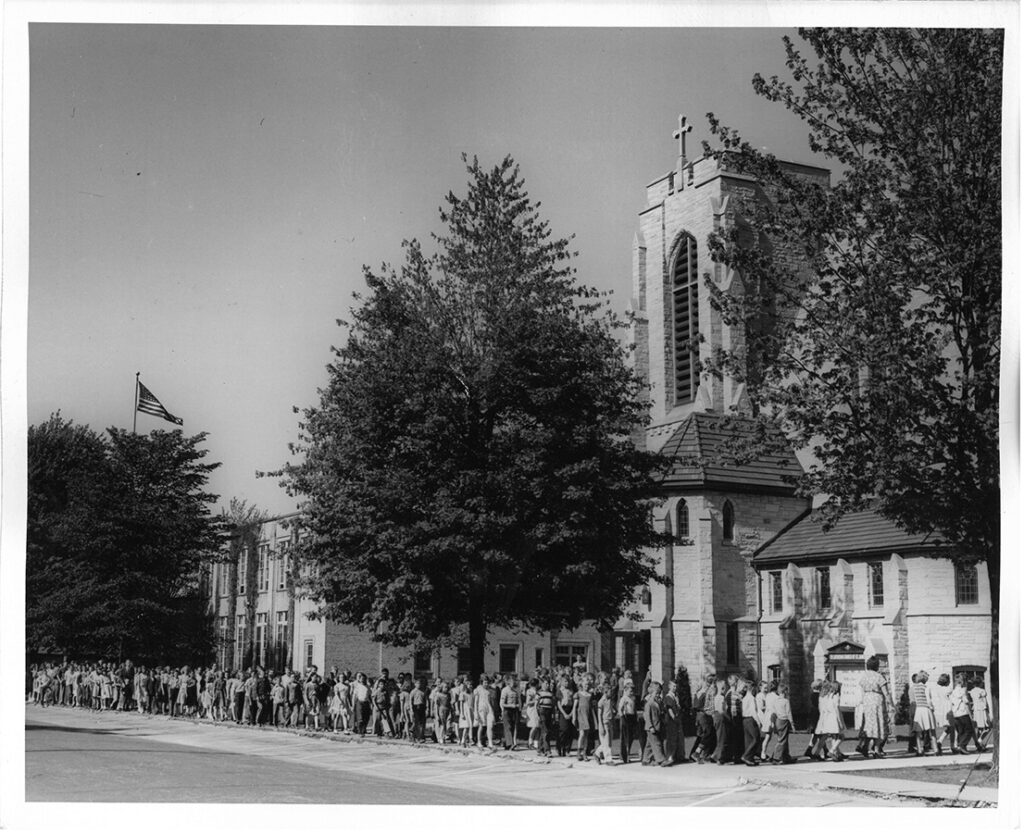

Growing with the Baby Boom: 1935–1965

As the American economy stabilized, Lutheran schools, too, saw an end to their declining numbers. A slow growth in enrollment beginning in the late 1930s accelerated through the ’40s and ’50s as America experienced the Baby Boom. Once again, the Synod’s supply of teachers could not keep up with the growing number of schools.

Meanwhile, state and federal government agencies began to regulate education more actively. LCMS schools generally sought to meet and even exceed the new academic standards adopted by their public counterparts. Teaching the Christian faith was still at the heart of Lutheran education. Educators spoke in new ways of addressing the “whole child” by offering an integrated education of both sacred and secular knowledge.

Holding Together Amid Social Fragmentation: 1965–2000

In the early 1960s, Synod publications proudly praised our schools and optimistically saw no end to their growth. However, enrollment in LCMS elementary schools peaked in 1965 and has generally been declining ever since.

Rising rates of divorce, working mothers and single-parent families in the 1970s and ’80s changed the home lives of many students. The LCMS began promoting early childhood education in the mid-’70s as another way to reach out to families. The number of Lutheran preschools swelled dramatically over the next 30 years. By 1991, freestanding LCMS preschools outnumbered elementary schools.

The early ’90s also marked the first time that non-Lutheran students outnumbered Lutheran ones in LCMS schools. In response to this shift, many schools expanded their spiritual focus from instructing baptized children in the Lutheran faith to evangelizing unchurched children in basic Christian teachings.

Looking to the Future: 2000 and Beyond

Today our LCMS schools face many questions: What role should technology play in education? How will school voucher programs assist or hinder Lutheran schools? Will enrollment declines and increasing costs force schools to close, or can our schools radically rethink how they operate in response to contemporary challenges? As we look to the future, our schools continue to find creative answers to these questions.

Regardless of the size or shape of Lutheran schools in the century to come, they will be blessed whenever and wherever they teach children the riches of God’s Word. As they instill these enduring truths in young minds and hearts, they will prove to generations to come that faithful Lutheran Christian education remains now what it has always been: the greatest earthly gift we can give our children.

1 The phrase “liberal education” here in the English translation is a gloss for “good books” or bonae litterae, referring to the treasures of a classical education.

2 The remainder of this article is adapted from Heather Smith’s “A Gift for Our Children,” originally published in the May 2018 issue of LW. Read the original article in its entirety here.

This article is adapted from a piece published in the August 2024 issue of The Lutheran Witness.

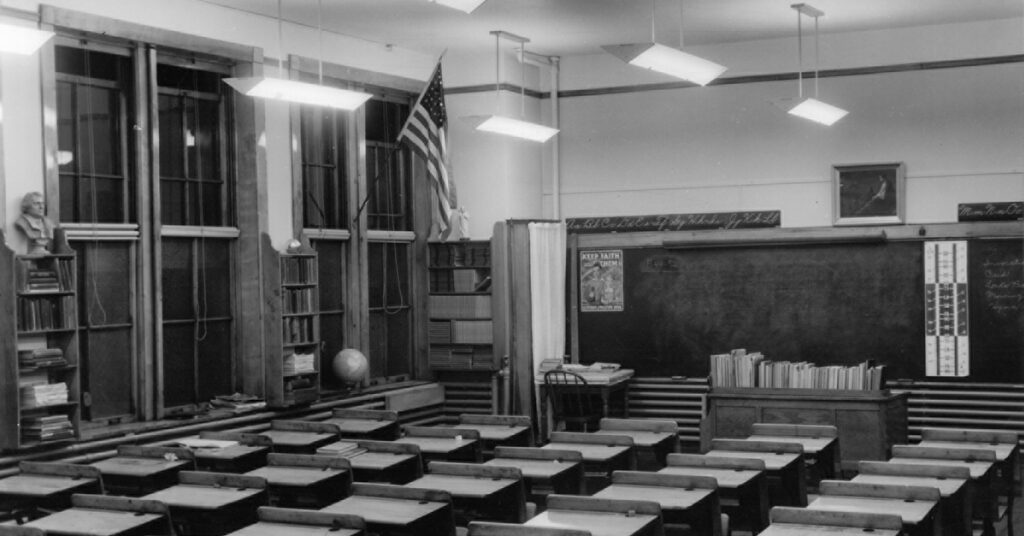

Images courtesy of Concordia Historical Institute, St. Louis; and LCMS/Erik M. Lunsford.

I was raised in a Lutheran school. Kindergarten-8th grade. (Albeit; WELS.) My 2 children were raised in an LCMS school. Preschool- 8th. Our church school. And attended Lutheran High, in Denver. My 4 grandchildren now attend the same LCMS elementary school. My son is an LCMS Pastor. My daughter now works for the Lutheran High school, now located in Parker, CO. Sadly, the LCMS elementary school my grandchildren attend has gone down in attendance considerably. But LuHi, the Lutheran High School where my daughter works, has boomed. Growing every year. Thanks be to God!

You hear little if anything from the Lutheran s.but they have the truth. May God grant his protection and dissemination of his truth for all.