Introduction

Food, Family, Work: The Sacred Mundane

What unites the human race, both across time and culture, far outweighs what divides.

As the years pass, I have come to serve a vocation that has taken me away from my extended family and deep rural and labor roots and cast me into complex contexts all over the world. I reflect more and more on the most basic things of this life. I’m not interested in institutions for their own sake. I withdraw from struggles about things that don’t matter.

Ours is but a moment, a flash of time here, not to be wasted. We so love to pontificate about how different our age is, how challenged we are, how unlike any other time is ours. Yet, I’ve seen life spanning the Stone Age to the Age of Technology, from aboriginal cultures in central Australia or southern Kenya, to Tokyo and Chennai, India sometimes on the same trip. Everything changes, but “there is nothing new under the sun.” What unites the human race, both across time and culture, far outweighs what divides.

What unites? In addition to sin, those great First Article issues— “everything I need to support this body and life.” And those of the Fourth Petition: “food, drink, clothing, shoes, house, home, field . . . good friends, faithful neighbors, and the like.” Luther recognized, as does the Bible, that we are communal beings. And life lived best is a life lived together, in love and mutual service.

I learned these lessons early. Every Sunday, we drove to little Lawton, Iowa, for church with the extended family. We received the Lord’s gifts together. Then we went to Bernie and Loraine’s for coffee. Then it was to Grandma and Grampa’s place for lunch—wonderful lunches! Ah, to be a boy again at that great oak table, filled with potato salad, coleslaw, corn on the cob, radishes right out of the garden. What a sacred blessing is food!

Food brought us together. It helped keep us a family—and still does. After lunch, the uncles would play cribbage and talk about the horrible politicians and how the world was falling apart. And we would laugh. We’d wrap up the evening watching Lawrence Welk and Disney, and head home in the dark. How a thousand such nights drifted so quickly into the past, I shall never comprehend.

Early on, we learned to work. Dad and Mom could do anything—and did it. That’s the way all farmers were. We watched and helped them do it all, and learned the value of work.

“Why do you do it that way, Dad?”

“It’s the right thing to do, Matt.”

From cement to plumbing to carpentry, roofing, painting, auto mechanics, freezing corn, and canning and dealing with some of life’s great challenges we learned something of it all. It wasn’t all roses, and still isn’t. We are sinners, but we know our Savior. In all and through all is Christ. I’ve always known I am baptized, and that Jesus loves all people and me.

It’s so easy to think that people who look different, talk different, or come from different places and cultures are fundamentally different from us. Believe me, the basics are the same: food, family, work—“good friends, faithful neighbors, and the like.” And because “no one is righteous, no, not one,” Christ is universal.

Very simply, the work of LCMS World Relief and Human Care addresses “food, family, and work,” and does so while speaking Christ’s Gospel and seeking wherever possible to include folks in the fellowship of the Church. People struggle in this world, often having no access to food or family or work or to Christ. Our “sacred mundane” vocation is right in front of us.

— Rev. Matthew Harrison

Reaching Out to the Hungry: from Appalachia to Africa

by Kim Plummer Krull

Even with today’s high food prices, “hunger,” for most of us, means working through lunch or eating less to trim our waistline.

But at the Our Savior Lutheran Church food pantry in Chillicothe, Ohio, needy families emptied the shelves of every canned good—even the lima beans, says Deaconess Deanna Cheadle.

In Chicago, a record line of people wound from the soup kitchen at St. Matthew Lutheran Church nearly out to the street. “That had never happened before,” Rev. Julio Loza says.

And in West Africa, longtime agricultural missionary Delano Meyer sees more people clearing land to farm and, he hopes, more potential participants for his biblically based agriculture training—one unexpected positive result of rising food costs.

Each of these ministries—and the people they serve— is affected by today’s economic challenges. And each ministry, over the years, has received critical support from LCMS World Relief and Human Care (LCMS WR-HC) and the ministry’s generous donors. Since 2005, development grants from the Synod’s mercy arm have helped feed more than 206,000 people and trained nearly 1,000 others to improve food production.

As Thanksgiving approaches, here’s a look at how blessings shared with LCMS WR-HC are a blessing to people in need, from Appalachia to Africa—and beyond.

Chicago Soup Kitchen Serves More Than Meals

In August, a line of about 80 people wound from the soup kitchen at St. Matthew Lutheran Church in Chicago, Ill., nearly out to West 21st street.

“That had never happened before,” says Rev. Julio Loza, who started the meal ministry in 1990 to serve the poor, ethnically diverse Pilsen neighborhood on the city’s Lower West Side. “As soon as one person finished eating and left, another person sat down.”

The summer’s high food and gasoline prices sparked record demand at El Comedor Popular (“the popular eating place,” in Spanish)—and, likewise, challenged this 138-year-old church with a fluctuating, generally low-income membership to feed about 300 people weekly.

“We’re the poor feeding the poor,” Loza says.

The congregation raises money through rummage sales, Mexican food catering, and constant appeals. But this summer, donations slowed to the point that St. Matthew closed two congregation-sponsored food ministries in Mexico. “It was a hard decision,” Loza says. “But we could no longer financially support them and respond to increased needs in Chicago.” After a brief hiatus, the church reopened the ministries with a donor’s emergency help.

In the ministry’s early years, St. Matthew turned to LCMS World Relief and Human Care for grants. “We approached them because we didn’t want to take government funding that would prevent us from being a witness for Christ,” Loza says.

Today, El Comedor Popular serves hot noon meals twice weekly, garnished with prayer and Scripture readings in English and Spanish. Former regular Tom Lopez says he is thankful the soup kitchen gave him more than meals.

Six years ago, the then unemployed bricklayer teetered on the edge of homelessness. Soup-kitchen volunteers made Lopez feel “warm and welcome.” Over time, he attended worship and even moved to the other side of the soup line to work as a volunteer.

Lopez took part in an alcohol-addiction program for veterans and now, at 52, is studying to become a counselor. St. Matthew, he says, provided “something that I needed in my life.

“It’s a blessing, a miracle,” adds Lopez, who now serves as St. Matthew’s congregation president.

Loza is determined such blessings continue, despite the church’s financial challenges. “The economy is affecting everyone,” he says. “But there are still people who have good jobs. And there are still people who send us donations every month, even though they are having a hard time, too.”

To learn more, visit stmatthewchicago.org.

At Ohio Food Pantry: Even Lima Beans Disappear

Every week for the past year, families in the western Appalachian community around Chillicothe, Ohio, have visited Our Savior Lutheran Church for groceries when their own shelves grow bare.

But in August, for the first time, “a family came in, and we had nothing to give,” says Deaconess Deanna Cheadle, who helped organize the food pantry as part of her work with nine LCMS congregations that comprise Diaconal OutReach and Care Services (DORCAS). “Usually, there’s something left—a canned good like lima beans. But this time, everything was gone.”

But in August, for the first time, “a family came in, and we had nothing to give,” says Deaconess Deanna Cheadle, who helped organize the food pantry as part of her work with nine LCMS congregations that comprise Diaconal OutReach and Care Services (DORCAS). “Usually, there’s something left—a canned good like lima beans. But this time, everything was gone.”

A record 14 families visited the food giveaway that week— around the same time that church members also were feeling the challenge of stretching dollars to stock the ministry and still feed their own families.

Throughout the year, 31 families turned to the church for food. In this sparsely populated rural area that’s a significant number, Cheadle says, adding that more than half the food pantry visitors are 70 or older. Many are unemployed because of disabilities.

One such couple is Herb and Meredith Mitchell, who told Cheadle they must limit their food-pantry treks because they could no longer afford the gas. This worries the deaconess, because the couple also confided that “they didn’t know what they would do” if not for Our Savior’s food distribution.

One such couple is Herb and Meredith Mitchell, who told Cheadle they must limit their food-pantry treks because they could no longer afford the gas. This worries the deaconess, because the couple also confided that “they didn’t know what they would do” if not for Our Savior’s food distribution.

In 2006, grants from LCMS World Relief and Human Care supplemented funds from the congregations and the Ohio District to hire Cheadle. Since then, Cheadle has helped members organize human-care programs, including the food ministry.

Congregation members staff the pantry. They tell visitors about church activities and ask for prayer requests. “We try and build relationships so we can share the Gospel as we care for them,” Cheadle says.

To help prepare for future needs, the DORCAS congregations are planning their first fund-raiser—a community fast they will promote like a walkathon. “We’ll ask people to fast for 30 hours and collect pledges for each hour,” Cheadle says of the event, set for May 2–3, 2009. The goal is to raise money for the food pantry and awareness about Our Savior. The church will host a fastbreaking community meal after Sunday worship.

“We also want people to notice hunger,” Cheadle says. “We want them to think about how they can choose to fast, but some cannot choose to be hungry.”

To learn more, visit lutheranDORCAS.org.

Higher Food Prices, Higher Regard for Farming in West Africa

While today’s global economic challenges spotlight serious problems, longtime agricultural missionary Delano Meyer says high food prices have at least one positive impact on West Africans.

“Now that the food situation is getting serious, we have many who are taking our training more seriously,” says Meyer, who, with his wife, Linda, helps farmers in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea improve agricultural practices and become better stewards of resources.

Africans can and must produce more food, says Meyer, who has led agricultural training in West Africa since 1994, supported by LCMS World Relief and Human Care and LCMS World Mission. Programs such as “Management of the Harvest” show farmers the causes for food shortages and help them find solutions. The Meyers follow up with biblical guidance, teaching how agriculture is a gift from God to use wisely.

“West Africa is abundantly blessed with agricultural potential not yet tapped,” says Meyer, who farmed in Minnesota for 22 years before becoming a missionary. He hopes today’s increasing food prices will help erase a generally negative African view of the farmer as lower class and prompt more young people to pursue agriculture.

One such West African is Lawrence, who has enthusiastically embraced the LCMS-sponsored training. In the past, Lawrence followed traditional “slash and burn” farming, cutting trees and torching land to prepare for planting. Today, the African follows the practice he learned in the “Harvest” program, mixing crop residue into the earth to better maintain long-term fertility.

Lawrence also assists the Meyers by teaching fellow farmers. “There are many fine Christians like Lawrence who have been very helpful to us and set a great example by their lives,” says Meyer, who also works with local West African Lutheran churches to address community needs.

Before the Meyers returned to Minnesota in May on furlough, they noticed more West Africans clearing farmlands, motivated by high food prices to plant more acres.

As the couple prepared to go back overseas in late summer, Meyer says he hoped to also see more West Africans in class— at this fall’s new agriculture training that will “teach people to know the Lord and show them how to wisely use this wonderful creation He gave us.”

To learn more, visit lcmsworldmission.org. Click on “International” and then “Africa.”

‘Cow Bank’s’ Four-Legged Loans Benefit Vietnamese Families

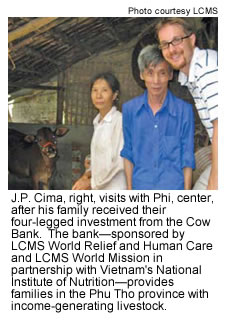

Phi and his wife warmly greeted J.P. Cima when he visited the Vietnamese couple this spring. But Cima knew the family was more excited about another arrival— their four-legged loan due any day from the “Cow Bank.”

“This cow will be a huge blessing for the family,” Cima says of the farmers, who live in a dirt-floor, thatched-roof home. The couple spoke enthusiastically about how the cow will transport tools and crops the three miles between their house and field. They look forward to future calves—and potential income.

Phi’s family is among those who have benefited from the Cow Bank, one of the most successful projects sponsored by LCMS World Relief and Human Care and LCMS World Mission, in partnership with Vietnam’s National Institute of Nutrition (NIN).

Phi’s family is among those who have benefited from the Cow Bank, one of the most successful projects sponsored by LCMS World Relief and Human Care and LCMS World Mission, in partnership with Vietnam’s National Institute of Nutrition (NIN).

Although the Southeast Asian country has made great strides since these nutrition and development programs began in 1995, inflation has hit many people hard. “The high costs of food and now building materials, too, has affected most families and has also meant that some families can no longer send their children to school,” says Rev. Ted Engelbrecht, LCMS World Mission’s Southeast Asia area facilitator.

Food costs are up at least 25 percent, with some provisions jumping 300 percent. Like most poor farmers, Phi’s family makes about $300 a year—approximately the cost of their new cow, which they received as a loan through the Cow Bank.

But instead of repaying their loan with money, the couple will give their first calf to another needy family. To date, the Cow Bank has provided cows to about 150 families in Phu Tho Province, northwest of Hanoi. In turn, those cows have produced calves for about another 150 families.

Last year, the NIN recognized LCMS World Relief and Human Care and LCMS World Mission for the Cow Bank and other projects—including those that have educated mothers about prenatal nutrition and taught farmers crop diversification. Much of today’s work targets poor families “left behind” during the country’s general economic improvement.

Although the government forbids evangelism, LCMS staff demonstrate God’s Word as they build relationships with the Vietnamese. The Cow Bank, Cima says, shares a stewardship message— for farmers such as Phi and his wife and for donors who make the project possible.

The Cow Bank, he adds, teaches financial responsibility, the importance of caring for precious resources, and that “even a little money can make a big difference in someone’s life.”

To learn more, visit lcmsworldmission.org. Click on “International” and then “Vietnam.”