by Timothy R. Furnish

“I believe in Jesus—just as a prophet, not as the Son of God.”

I’ve had this discussion numerous times over the years—at Starbucks, in college faculty offices, online with old friends who had “fallen away.” So the subject wasn’t novel; what was new, however, was the location and the speaker: the dining room of Hotel Laleh in Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran, and a friendly Iranian studying to become a mullah (Islamic cleric).

I’ve had this discussion numerous times over the years—at Starbucks, in college faculty offices, online with old friends who had “fallen away.” So the subject wasn’t novel; what was new, however, was the location and the speaker: the dining room of Hotel Laleh in Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran, and a friendly Iranian studying to become a mullah (Islamic cleric).

I was in Iran for the fourth annual conference on Mahdism in August 2008. Mahdism is the Islamic belief in al-Mahdi, “the rightly guided one” who will come before the end of time to make the entire world Muslim. Both major branches of Islam, Sunni and Shi`i, hold this Mahdist belief, despite his absence from the Qur’an.

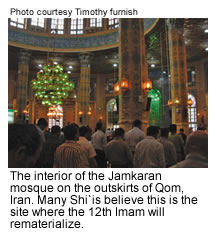

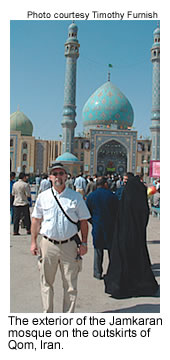

The Mahdi appears, rather, in the Hadiths, or “sayings,” attributed to Islam’s founder, Muhammad (d. A.D. 632). Sunnis, the majority of Islam’s 1.3 billion adherents, believe that the Mahdi has not yet appeared; Shi`is, about 15 percent of the world’s Muslims, believe that the Mahdi has already been here, as one of Muhammad’s descendants through his son-in-law and cousin Ali. The largest branch of the Shi`a, the “Twelvers” of Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon, believe that it was the 12th descendant—also named Muhammad—who did not die but “disappeared” in A.D. 874 and who will return as the Imam al-Mahdi, of whom President Ahmadinejad of Iran speaks constantly.

Ahmadinejad was the keynote speaker at the opening session, but rather than harping on purely political grievances against the West (Palestine and Iraq, for example), he emphasized the imminent coming of the Twelfth Imam and how the process of globalization was Allah’s way of preparing the world for it. The various sessions of the conference all echoed this theme of the Mahdi’s impending arrival, and how the Islamic Republic of Iran was in the vanguard of paving the way for his coming.

Ahmadinejad was the keynote speaker at the opening session, but rather than harping on purely political grievances against the West (Palestine and Iraq, for example), he emphasized the imminent coming of the Twelfth Imam and how the process of globalization was Allah’s way of preparing the world for it. The various sessions of the conference all echoed this theme of the Mahdi’s impending arrival, and how the Islamic Republic of Iran was in the vanguard of paving the way for his coming.

This included some unsettling topics: For example, one Iranian presenter discussed the future status of Jews and Christians under the Mahdi’s rule—would we all be converted or killed? It was not overly reassuring to hear that “most likely, the Mahdi will simply convert Jews and Christians.” There was little or no differentiation between religious and political (or even military) topics: thus panels discussed issues such as the Islamic “anti-christ” (al-Dajjal, “the Deceiver”); the role of jihad, or “holy war,” in Mahdism; and the type of governors the Mahdi will appoint to rule over non-Islamic lands.

Two Goals

It was clear that the conference—and the sponsoring, government-funded Bright Future Institute—had a dual aim. On one level, it was an attempt to spread Mahdism among Sunni Muslims, to convince them it’s acceptable to believe in the Mahdi; for despite the existence of Mahdism in Sunni circles, a minority therein has always rejected the belief because of (1) the lack of Qur’anic support for the Mahdi; (2) the near-heretical divinizing of the 12 Imams practiced by many Shi`is; (3) the history of bloodshed between Sunnis and Shi`is, going back to Islam’s earliest days in the Seventh Century.

Still, Shi`i Iran is hoping to rival Sunni Saudi Arabia as the leading Islamic nation, and is trying—with some success—to use belief in the Mahdi as leverage to do so. But the ayatollahs who rule Iran are also trying to gain influence in the non-Muslim world by pushing Mahdism among Jews and particularly Christians, claiming that the messianic hopes of both religions will be fulfilled in the Twelfth Imam, the Mahdi.

For example, several Americans (both lay and ordained) courted most aggressively by the Iranians were representatives of Christian denominations whom we might refer to as “ecumaniacs”—pursuing “interfaith dialogue” for its own sake. Mahdism is thus being used as both a political and religious “evangelism” tool by Iranian Shi`is.

For example, several Americans (both lay and ordained) courted most aggressively by the Iranians were representatives of Christian denominations whom we might refer to as “ecumaniacs”—pursuing “interfaith dialogue” for its own sake. Mahdism is thus being used as both a political and religious “evangelism” tool by Iranian Shi`is.

But evangelism attempts can cut both ways. I befriended several of the conference organizers, in particular a mullah-in-training (mullahs are rather like priests, whereas an ayatollah is similar to a bishop or archbishop). He and I began by discussing ways of interpreting the Qur’an, good-naturedly arguing whether the strict literalist Sunnis or the more allegorical-minded Shi`is had the correct approach to issues such as jihad. As the week progressed, our periodic conversations turned to Jesus in Islam and Christianity, and what the Bible and Qur’an say about Him.

What my colleague knew was what Islamic propagandists had taught him: for example, that the Counselor, or Advocate, Jesus promised to believers in John 14:16 refers to the eventual coming of Muhammad. Islamic apologists argue that the Greek parakletos (“advocate, helper”) should be read periklutos (“praised”)—because the Arabic root hamada, whence comes the name Muhammad, means “praised.” As former Anglican Archbishop of Jerusalem, and Islam scholar, Kenneth Cragg says: “This charge and the Muslim alteration have no basis exegetically. Nor does the sense of the passage bear the Muslim rendering. . . . However painful the necessity, the Christian must cheerfully shoulder the task of distinguishing clearly between Muhammad and the Holy Spirit, and of appreciating how it comes that the Muslim can be so confidently confused at this point” (The Call of the Minaret, 1964, p. 285).

The Jesus We Believe In

I’m not sure how cheerful I was, but I did try to follow Archbishop Cragg’s advice. Mid-week of my stay in Iran I asked my Muslim friend if he’d ever read the Bible. “No,” he wistfully explained. “Wait here,” I told him. I went to my room and came back with my small volume of the New Testament, Psalms, and Proverbs—U.S. Army-issue, with a camouflage cover, ironically—which I gave him.

I’m not sure how cheerful I was, but I did try to follow Archbishop Cragg’s advice. Mid-week of my stay in Iran I asked my Muslim friend if he’d ever read the Bible. “No,” he wistfully explained. “Wait here,” I told him. I went to my room and came back with my small volume of the New Testament, Psalms, and Proverbs—U.S. Army-issue, with a camouflage cover, ironically—which I gave him.

He tucked it away, no doubt knowing full well that while the official government position is that Iranians have complete religious freedom, the reality is quite different. I don’t know if he’d had time to read any of it, but a few days later as the dinner dishes from my last meal in Iran were being cleared to make way for coffee and tea, the conversation again turned to Jesus, and my colleague repeated the line about Jesus being a great prophet and how Muslims and Christians could rally around that belief. “No, my friend,” I told him, “that is not the Jesus we believe in. We believe He was the Son of God, crucified and resurrected to atone for our sins.” I was seconded in this by a French Catholic scholar sitting at our table. My Iranian colleague then asked, “How could one man’s sins take care of another’s?”

“Because,” I replied, “He was not just a man—He was God’s Son.” We discussed this for a few minutes, until some ayatollahs sat down near us—at which point we decided discretion might be the better part of valor. But I encouraged my Muslim friend to read the Gospels and the rest of the New Testament and compare them to what the Qur’an says about Jesus. Who knows? Maybe someday at least one member of Iran’s clerical leadership will have a true view of Jesus as Messiah, or who at least, like Nicodemus, can come to Jesus by night.

Iran is funding and supporting a worldwide effort to spread Shi`i messianic beliefs among Christians, even in the United States, via organizations such as the Islamic Information Center in Washington, D.C. We need to be aware of this, and prepared to share with them “the faith once for all entrusted to the saints” (Jude 3) in the true Messiah, Jesus Christ.

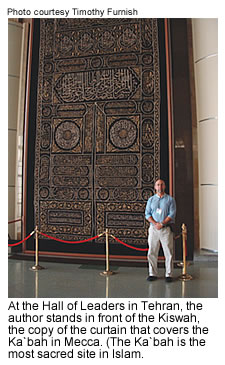

A writer, editor, and teacher, Timothy R. furnish (above) received his M.A.R. from Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, in 1989 and a Ph.D. in Islamic history from Ohio State University in 2001. He is the author of Holiest Wars: Islamic Mahdis, their Jihads and Osama bin Ladin (Praeger, 2005) and an elder at Rivercliff Lutheran Church in Sandy Springs, Ga. He operates a Web site dedicated to studying Mahdism: www.mahdiwatch.org.

Islam: A Time Line

Islam is the youngest of the monotheistic religions, developing some six centuries after jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection. Because both Christianity and Islam claim to be God’s true revelation to mankind, and because of the geographical proximity of the states where each was the dominant religion, the two faiths have often been in armed conflict.

for the first millennium of Islam’s existence, it was expansionist and often militarily successful (with notable exceptions such as the first Crusade and the Ottoman failures to conquer all of Europe). But starting in the 18th century, Western powers (Russia, Britain, france, and eventually the United States) became militarily and politically dominant over the Islamic world, a status that still exists today.

A.D. 622/1 AH (after hijra) “Flight” of Muhammad and first followers from Mecca to Medina.

632 Death of Muhammad.

661 Murder of Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law and first in line of Shi`ite imams.

632–1000 Islamic conquests across Middle East, Persia, North Africa, and Spain.

732 Invading Islamic army defeated at Tours, France.

874 Death (disappearance, in Shi`ite belief) of 12th Shi`ite Imam, who will return as al Mahdi to Islamize the world.

1099–1291 The Crusades.

1453 Conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turkish Empire.

1492 Last Moorish (Islamic) kingdom in Spain falls. Muslims (and Jews) expelled from Spain. Columbus discovers the new world.

1501–1524 Iran/Persia forcibly converted to Shi`ism by Safavid Shah Isma’il.

1529 Ottomans besiege Vienna.

1571 Battle of Lepanto: combined European Christian fleets defeat Ottoman navy.

1798–1936 British and French imperialism in Middle East.

1918–22 Ottoman Empire collapses after World War I.

1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran.