Like Daniel in the lion’s den, Philip Melanchthon faced the papal legate Lorenzo Campeggio at Augsburg in 1530. The representative of the pope thundered and flashed bolts of lightning at the Wittenberg professor. The two confronted each other head to head in negotiations over the future of the Wittenberg Reformation sparked by Luther in 1517.

Philip Melanchthon: Photo: wikimedia For a brief photo tour of Melanchthon’s house in Wittenberg, click here.

That is how Nikolaus Selnecker, Melanchthon’s student and one of the authors of the Formula of Concord (1577), depicted the tension-filled situation at the Augsburg Diet (assembly) of the German empire in June 1530. There, Melanchthon directed efforts to confess the faith of Martin Luther, himself, their colleagues, and the government officials who were introducing their program for reform in their lands. Selnecker was telling his students the story of the confession at Augsburg. He

related how Campeggio bared the claws of Satan himself with his intimidating snarl. “Saint Philip stood as if in the midst of lions, wolves, and bears which could tear him into little bits and pieces,” Selnecker said. “But he displayed a superabundance of splendid courage in his slight frame, and he answered boldly, ‘We commit ourselves and our cause to God, our Lord.’”

Different opinions of the author of the Augsburg Confession existed in competition with each other when Melanchthon died 450 years ago, on April 19, 1560. He had been Luther’s closest aide and associate in reform. But, as Selnecker well knew, some disciples of Melanchthon were portraying him as a shy, retiring man, the victim of other students who had betrayed him. On the other hand, those who had developed deep suspicions and feelings of betrayal toward their beloved “preceptor” (teacher) regarded him as a traitor. The reason lay in his pursuit of a policy of compromise in his effort to save Lutheran reform after Emperor Charles V decisively defeated the armies of the leading Lutheran princes at the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547.

Charles and his imperial government were attempting to force their churches back into submission to the papacy. Melanchthon was making every effort to save Lutheran preachers in Saxony from being driven into exile, but these followers believed hiscourse to be false and compromising. Nonetheless, even they acknowledged him as their preceptor, who had taught them how to think as biblically faithful theologians. They never lost their appreciation for the preceptor who had educated them to preach and teach with intellectual depth and scriptural insight. They used his teaching and his way of thinking in arguing against the policies he was pursuing.

Selnecker belonged to another group of those who had studied in Wittenberg. This group sometimes departed from Melanchthon’s positions, but their devotion to the man who had shaped the way they thought never faltered. In 1575, Selnecker delivered an oration on the professor who had welcomed him a quarter century earlier into his own home. He recalled the toughness that Melanchthon had consistently displayed when Luther’s teaching on the justification of sinners through faith alone on the basis of the death and resurrection of Christ was at stake. But that was only one facet of a complex man who did more to mold the Lutheran church than anyone else other than Luther himself.

An Intellectual Leader

Philip, as Luther called his colleague and friend, arrived in Wittenberg in 1518, a prime catch for a university without a reputation, scarcely a decade old. For at 21, Melanchthon had a reputation as a Wunderkind, a young genius who was certain to provide intellectual leadership throughout the German empire and beyond. That he did. His textbooks in communication theory—called rhetoric and dialectic in his day—were reprinted, not only throughout Protestant lands into the 18th century, but also in Catholic regions, where they appeared from Roman Catholic presses, albeit with the name of the author omitted from the title page.

Like any great movement, the Lutheran Reformation was led by a team. If Luther was its captain and inspiration, Melanchthon was his right-hand man. He executed many of the practical tasks that conveyed the teaching of the Wittenberg team to wider audiences. Luther was prophet; Melanchthon, preceptor. He not only taught students how to preach and teach, how to communicate effectively with the gifts God creates and bestows for profitable human exchange, he also encouraged colleagues to explore God’s creation, on which both he and Luther focused so much attention, through the study of history and literature, astronomy and botany. His leadership made Wittenberg a university so famous that Shakespeare took it for granted that his Danish Hamlet would have studied there.

Though never ordained, and shy of preaching because of a slight speech impediment, Melanchthon contributed much to the Wittenberg reform movement. He not only encouraged the study of God’s First Article gifts, he also promoted biblical studies and the public conveying of the faith through teaching and proclamation. He mastered Greek and Hebrew early in his career as a student. This gave his lectures on Scripture theological depth. The commentaries published on the basis of these lectures served as aids to preachers who left Wittenberg’s lecture halls for pulpits across Germany and Europe. They served as models for professors at other universities in their own training of new generations of pastors. In addition, his adaptation of the “topical” method (in Latin, loci communes) for organizing biblical material and selections from the writings of the Church Fathers provided the foundation for Lutheran doctrinal instruction to this day.

The ‘Variata’

Melanchthon was a public figure beyond the university. He commanded the confidence of his own princes, particularly Elector John and his son John Frederick, who put their lives on the line with the Augsburg Confession in 1530. Both father and son employed Melanchthon as part of their diplomatic corps. He negotiated with representatives of the kings of France and England, as well as his own emperor, Charles V, on repeated occasions in order to win adherence for Luther’s teaching or at least tolerance for the spread of his reforms.

In this role, as the one who was designated to lead negotiators in conversations with Roman Catholics from the emperor’s entourage in 1539–42, Melanchthon followed John Frederick’s order to update the Augsburg Confession. The so-called “Variata” was later seen as an evil attempt by Melanchthon to subvert the Lutheran teaching on the Lord’s Supper through a change in the wording on the Sacrament. In fact, Philip revised the princes’ confession most extensively by expanding its rather brief explanation of the doctrine of justification. He did that because John Frederick wanted that doctrine more explicitly set forth in what the Elector regarded as his public statement of faith. In fact, that is what Melanchthon had composed it in 1530 to be.

It was to preserve the proclamation of justification by faith in Christ that Melanchthon made one of the most serious moves of his life. Caught in political crosscurrents after John Frederick’s imprisonment by Charles V a year after Luther’s death, Melanchthon contributed to efforts by his new overlord, John Frederick’s cousin, Elector Moritz, to stave off an invasion of his lands by the emperor. Melanchthon and his colleagues in Wittenberg fought against excessive concessions to Charles V, but they did formulate certain compromises in “adiaphora,” neutral practices neither commanded nor forbidden by Scripture. Many of his students regarded these concessions as a betrayal of the truth and the Reformation because of the impression they would convey to the common people. Melanchthon in turn felt betrayed by these students. He thought they should have understood his striving to prevent Lutheran preachers in north Germany from being driven from their pulpits, as had already happened in 1548 in south Germany.

Disappointment and Tragedy

Melanchthon’s bitter disappointment over the sharp attacks from these students was not the only tragedy that haunted his life. One son died in his second year. Acrimony over marriage plans clouded the relationship of his wife and himself with their older son. A trusted student married one of his daughters and maltreated her so badly that she died when she was but 24 years old. He did not live to see his other son-in-law, Caspar Peucer, who had become his staff and stay after the death of his wife in 1557, go to jail for “crypto-calvinistic” ideas.

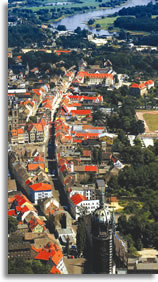

Aerial photo of Wittenberg

Photo: wikimediaPeucer taught astronomy and then medicine at Wittenberg. He may have influenced Melanchthon in his last years to depart from his earlier understanding of the presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. That stance earned both Peucer and his father-in-law harsh criticism from other students of both Luther and Melanchthon himself. They condemned him sharply for abandoning Luther’s way of affirming of the true presence of Christ’s body and blood in the bread and wine. Melanchthon had never used exactly the same language as Luther did; neither he nor his senior colleague realized that Melanchthon was supposed to be Luther’s clone.

While Luther lived, the two taught and worked alongside each other without public friction. Both confessed faith in the atoning work of Christ and spread the message they had developed together. But Melanchthon did develop new perspectives and convictions in the 14 years he lived after Luther’s death.

Recent scholarship has suggested that the charge often lodged against Melanchthon of having abandoned Luther’s emphasis on salvation by grace alone contradicts the sources. It is true that Melanchthon did use different expressions than Luther in using God’s law to call sinners to exercise their God-given responsibilities to trust and obey their Lord. But Melanchthon did not speak of salvation without striving to make clear that rescue from sin and death comes only through God’s gracious action, totally undeserved as the Holy Spirit bestows a living faith upon those whom God calls into his kingdom through the Word of the Gospel of Christ.

The censure of Melanchthon that developed toward the end of his life, largely around the issues of his views of the role of the human will in conversion and of Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper, have clouded “the Preceptor’s” reputation for much of Lutheran history. Nonetheless, he stands as the one who expressed Wittenberg teaching in the Augsburg Confession of 1530, a document that remains the fundamental definition of what it means to be Lutheran. As parts of the Book of Concord, his defense of that confession, the Apology of the Augsburg Confession (1531), and his Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope (1537) continue to determine the Lutheran expression of the biblical message.

Therefore, as we reflect on his death 450 years ago, we thank God that he confessed our faith in the Augsburg Confession. We recognize Philip Melanchthon as one who has put words of confession of the faith in our mouths, as one who remains our preceptor as well.

What Was Crypto-Calvinism?

Toward the end of Melanchthon’s life, as some of his students at the University of Wittenberg and in the Electorate of Saxony pondered their preceptor’s lectures and conversations about Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper and the relationship of Christ’s divine and human natures, they developed Melanchthon’s ideas in a direction that seemed to others, and perhaps even to themselves, as similar to those of the Genevan reformer John Calvin. Their ideas probably did not derive as much from their reading of Calvin as their listening to Melanchthon.

The Crypto-Calvinists, led by Christoph Pezel, a young professor of theology who had studied only briefly under Melanchthon, and Melanchthon’s son-in-law, Caspar Peucer, taught that Christ was spiritually present in the Lord’s Supper, and that the believer’s soul received all the benefits of His death and resurrection when the believer ate the bread and wine of the Supper. Also, they taught that Christ’s human body and blood were situated in heaven and could not be in more than one place at one time.

Their Lutheran opponents held, as Luther had taught, that because the divine and human natures of Christ share their characteristics (the ancient doctrine of “the communication of attributes”) Christ’s body and blood could indeed be present in whatever form, including sacramental form, that God willed them to be. Led by Martin Chemnitz, they repeated Luther’s conviction that in the unique union of bread and wine with Christ’s body and blood, based on His own words, He gives believers forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation.

Melanchthon: A Timeline

We commemorate Philip Melanchthon on Feb. 16, his natal day (Lutheran Service Book, xii).

| 1497 | Born Philipp Schwartzerd in Bretten, in southwest Germany. | |

| 1518 | Appointed professor in Wittenberg after study in Heidelberg and Tübingen. | |

| 1520 | Marries Katherina Krapp, daughter of the mayor of Wittenberg. | |

| 1521 | Writes the first edition of his Loci communes theologici as a guide to reading Romans. | |

| 1530 | Composes the Augsburg Confession, and in 1531 the Apology of the Augsburg Confession. | |

| 1546 | Praises Luther in his funeral oration for his mentor. | |

| 1548 | Aids in writing the “Leipzig Proposal,” which earned him much criticism. | |

| 1557 | Death of Katherina, his beloved wife. | |

| 1560 | His own death. |

Unfortunately, popular English biographies of Melanchthon are rare. (Heinz Scheible’s biography in German is very good, but it is not available in English.)

Perhaps the best English resource is Heinz Scheible’s “Philip Melanchthon” in The Reformation Theologians, edited by Carter Lindberg (Oxford: Blackwell, 2002). It is not much, and it is, perhaps, not easy to find. If you would like to become more familiar with Melanchthon, a good place to begin is with his writings: the Augsburg Confession and its Apology, and the Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope, all from the Book of Concord.

Pingback: St. Philip Melanchthon

reading in the LSB page 1873, I found a reference to Melanchthon in the notes: he listed 9 proofs that God exist…..yet I cannot find this reference anywhere else. I would like to see this published with some details over and above what is found on page 1873