“The Lord possessed me at the beginning of his work,

Proverbs 8:22–31

the first of his acts of old.

23 Ages ago I was set up,

at the first, before the beginning of the earth.

24 When there were no depths I was brought forth,

when there were no springs abounding with water.

25 Before the mountains had been shaped,

before the hills, I was brought forth,

26 before he had made the earth with its fields,

or the first of the dust of the world.

27 When he established the heavens, I was there;

when he drew a circle on the face of the deep,

28 when he made firm the skies above,

when he established the fountains of the deep,

29 when he assigned to the sea its limit,

so that the waters might not transgress his command,

when he marked out the foundations of the earth,

30 then I was beside him, like a master workman,

and I was daily his delight,

rejoicing before him always,

31 rejoicing in his inhabited world

and delighting in the children of man.”

St. Athanasius (a.d. ca. 298–373) was five years old when the last and greatest persecution under the Roman commenced. The Diocletian persecution lasted eight years; Athanasius lived through it and was formed by it. It was likely during this time that Athanasius was taken to the desert and lived with St. Antony, who is known as the father of monasticism. Later Athanasius wrote the Life of St. Antony. When he was fifteen, the Emperor Constantine saw the banner of the cross in a vision and provided not only peace for Christians in the Edict of Milan (313), but he also made Christianity the religion of the empire. When Athanasius was twenty years old, an Alexandrian Presbyter named Arius began teaching that there was a time when the Son of God was not. Athanasius attended the Council of Nicaea in 325 as a deacon. Three years later he was elevated to Patriarch of Alexandria and as such took aim at this rank Arian heresy.

Athanasius served for 45 years as Bishop of Alexandria, 17 of which were spent in exile. What appeared to be a great victory over Arius at the Council of Nicaea (from which we get a draft of what would become later our Nicene Creed) was hardly such a victory. The empire teetered and tottered from the orthodoxy of the Christian faith to the heretical claims of Arianism. For Athanasius, everything depended on Christ being God.

Between a.d. 356 and 360 (his third exile), Athanasius wrote his treatise Four Discourses against the Arians. It revealed that the Arian debate was a Scriptural debate. Athanasius states in his introduction:

But, whereas one heresy, and that the last, which has now risen as harbinger of Antichrist, the Arian, as it is called, considering that other heresies, her elder sisters, have been openly proscribed, in her craft and cunning, affects to array herself in Scripture language, like her father the devil, and is forcing her way back into the Church’s paradise…on this account I have thought it necessary, at your request, to unrip “the folds of its breast-plate,” and to shew the ill savour of its folly. So while those who are far from it may continue to shun it, those whom it has deceived may repent; and, opening the eyes of their heart, may understand that darkness is not light, nor falsehood truth, nor Arianism good; nay, that those who call these men Christians are in great and grievous error, as neither having studied Scripture, nor understanding Christianity at all, and the faith which it contains.

Athanasius, “Discourse I, I.1”; NPNF 2nd Series, 4:307

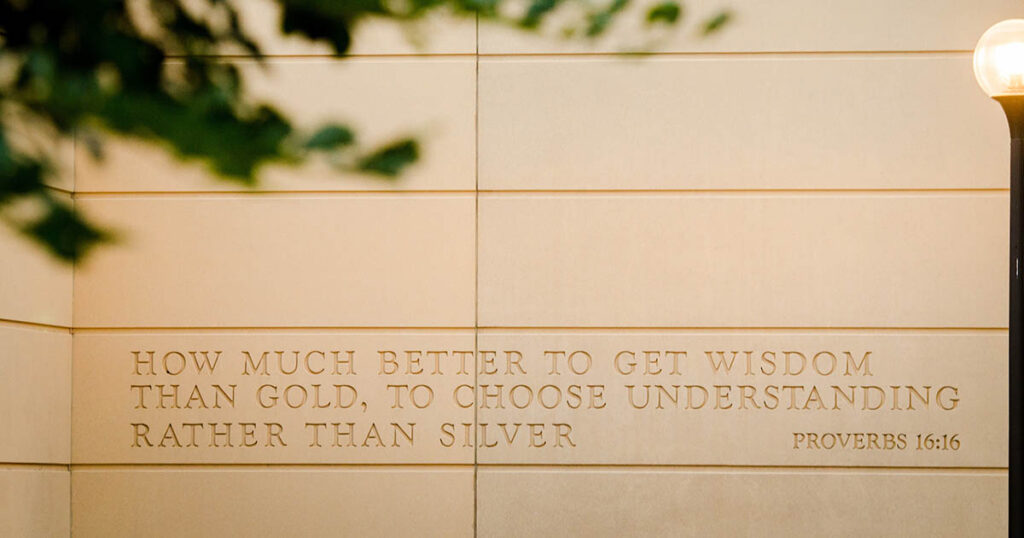

One might think that the basis for Christological debate would rest in the New Testament. But by far the lengthiest argument centers on Proverbs 8:22–31, more than a quarter of the whole work. Consider this short excerpt from St. Athanasius on Proverbs 8:

We have gone through thus much before the passage in the Proverbs, resisting the insensate fables which their hearts have invented, that they may know that the Son of God ought not to be called a creature, and may learn lightly to read what admits in truth of a right explanation. For it is written, “The Lord created me a beginning of His ways, for His works;” since, however, these are proverbs, and it is expressed in the way of proverbs, we must not expound them nakedly in their first sense, but we must inquire into the person, and thus religiously put the sense on it. For what is said in proverbs, is not said plainly, but is put forth latently, as the Lord Himself has taught us in the Gospel according to John, saying, “These things have I spoken unto you in proverbs, but the time cometh when I shall no more speak unto you in proverbs, but openly.” Therefore it is necessary to unfold the sense of what is said, and to seek it as something hidden, and not nakedly to expound as if the meaning were spoken “plainly,” lest by a false interpretation we wander from the truth. If then what is written be about Angel, or any other of things originate, as concerning one of us who are works, let it be said, “created me;” but if it be the Wisdom of God, in whom all things originate have been framed, that speaks concerning Itself, what ought we to understand but that “He created” means nothing contrary to “He begat?” Nor, as forgetting that It is Creator and Framer, or ignorant of the difference between the Creator and the creatures, does It number Itself among the creatures; but It signifies a certain sense, as in proverbs, not “plainly,” but latent; which It inspired the saints to use in prophecy, while soon after It doth Itself give the meaning of “He created” in other but parallel expressions, saying, “Wisdom made herself a house.” Now it is plain that our body is Wisdom’s house, which It took on Itself to become man; hence consistently does John say, “The Word was made flesh;” and by Solomon Wisdom says of Itself with cautious exactness, not “I am a creature,” but only “The Lord created me a beginning of His ways for His works,” yet not “created me that I might have being,” nor ‘because I have a creature’s beginning and origin.

Athanasius, “Discourse II,” XIX.44

Now, it is striking the way that “Wisdom,” who speaks in Proverbs 8, is assumed by both Athanasius and the Arians to be the Lord, the eternal Word of the Father. If Athanasius and the orthodox theologians of Nicaea simply argued that this isn’t Jesus speaking, the work would have been substantially shorter. However, they were convinced from the text itself that this Wisdom is Christ Himself, as St. Paul says, “Christ, the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Cor. 1:24).

Part of the problem in the fourth century was that they didn’t often know the Hebrew language. They struggled over a Greek term that could mean anything from “create” to “possess;” the Hebrew is much clearer and is rightly translated, “possess.” In any case, the point is this: Because no one in the Early Church — even those Arian heretics — could imagine Wisdom to be anything other than Christ, what does it mean for Christ to be created?

Granting the word meant created, St. Athanasius demonstrates from the text itself that the meaning must derive from how we are to read proverbs, “latently.” To read them literally is to read them according to how they are given, as Athanasius says, “we must not expound them nakedly in their first sense, but we must inquire into the person, and thus religiously put the sense on it.” This isn’t some arbitrary interpretation, nor is it proof-texting, nor is it reading back into the Old what is evident in the New. It’s letting this Old Testament text pressure us into seeing the Lord’s Trinitarian essence. As Athanasius says later, “For the very passage proves that it is only an invention of your own to call the Lord creature. For the Lord, knowing His own Essence to be the Only-begotten Wisdom and Offspring of the Father, and other than things originate and natural creatures, says in love to man, ‘The Lord created me a beginning of His ways,’ as if to say, ‘My Father hath prepared for Me a body, and has created Me for men in behalf of their salvation.’”[1] What is created is not Wisdom per se, but the body given at the incarnation. Wisdom is only “created” in the sense that Christ received flesh in the incarnation.

For St. Athanasius and the early Christians, it was simply a matter of who God is as He reveals Himself in the Holy Scriptures. He is three in one — “a Trinity in Unity and a Unity in Trinity” — as the Athanasian Creed says. And God is this Holy Trinity bothin the Old Testament and in the New Testament because there’s only one God. As Athanasius says, “But God’s Word is one and the same, and, as it is written, ‘The Word of God endureth for ever,’ not changed, not before or after other, but existing the same always. For it was fitting, whereas God is One, that His Image should be One also, and His Word One, and One His Wisdom.”[2] And it’s through this Wisdom, the eternal Word and Lord, that we, too, find our creation. Thanks be to God.

[1] Athanasius, “Discourse II,” XIX.47.

[2] Athanasius, “Discourse II,” XVIII.36.

Thank you for this article Rev. Boyle.