Over the years some have suggested that the reforms of the Second Vatican Council (known as Vatican II) of the Roman Catholic Church “messed up” our Lutheran observance of Palm Sunday by inserting the Passion account into the day. Some have further suggested that the Passion on Palm Sunday is an accommodation to those who might skip the services of Maundy Thursday or Good Friday. But that’s not really the case.

Palm Sunday, as we know it today, is an amalgamation of two distinct lines of the church’s tradition: the palm branch custom of the Jerusalem church of the fourth century and the Western Church tradition prior and parallel to that of reading the Passion narrative. The Palm Sunday we know, as it’s given (admittedly rather abbreviated) in Lutheran Service Book (LSB), is where those two lines meet.

A pilgrim’s tale

If you went back to fourth-century Jerusalem, you’d meet a Spanish pilgrim named Egeria. We don’t know much about her except that she traveled extensively throughout the Holy Land from about A.D. 381 to 386, keeping a very detailed travelogue of her journey — what, when and how various days and holy days were celebrated and observed. Her account has survived to this day.

For the Sunday before Easter, she notes that for the morning ceremonies and Divine Service “everything” is done “as usual” — her phrase for when what’s done in Jerusalem is the same as back home in Spain — except for the afternoon. Around noon or one o’clock, everyone gathers on the Mount of Olives for a service of prayer and readings, then they process with palm and olive branches to the place where Jesus ascended, and they offer more prayers and readings. Then they process with their branches back into Jerusalem for the afternoon services around five o’clock.

At that same time, however, in the Western Church — even in Egeria’s Spain — we find no mention of palms or Palm Sunday in either the readings for the Divine Service or in the names for the Sunday (of which there were many). Rather, the focus for that Sunday is on the Lord’s Passion; St. Matthew’s account was the standard.

But that begins to change, and in a way that’s similar to what still happens today. When you go on vacation or visit a different congregation, perhaps you bring a bulletin back to show your pastor. Maybe you even suggest, “This congregation did such and such a thing … could we try that here?” Thanks to pilgrims like Egeria (and many countless others whose names and accounts are lost to us) the palm theme migrates to other Christian communities. It first shows up, as you might guess, in Spain by the fifth century. Over the course of the next 500 years, it spreads from Spain into Gaul (modern-day France) then into Germany. Around the end of the sixth century, the practice had already been used, in modified form, in Rome.

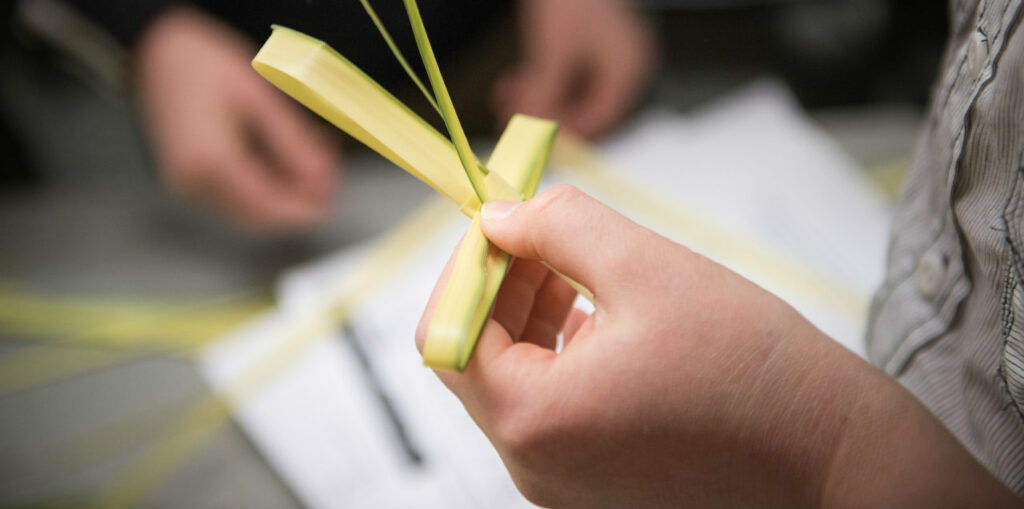

As palm ceremonies meet the tradition of reading the Passion accounts in the West, they remain a bit distinct. The “liturgy of the palms” is placed prior to the Divine Service, as the Passion maintains preeminence in the Divine Service; our Palm Sunday rite in LSB still maintains this tension. However, over the course of 1,100 years, the ceremonies of the palm rite expand.

Reformation adjustments

By the time of the Reformation, the palm rite with the triumphal entry Gospel had become, essentially, a full, separate “Divine Service” culminating in, not the reception of the Lord’s body and blood, but the reception of the blessed palms. In any given region, you could find that basic structure of the Divine Service for the palms: psalmody and antiphons, up to six prayers of blessing, multiple readings, sometimes a brief sermon and finally the “consecration” of the palms with its own Proper Preface, the singing of the Sanctus, the praying of the Lord’s Prayer and, finally, the distribution of the palms.

So what about the Lutherans? Well, amongst us, you found both the full rite with the Passion or “just” Palm Sunday. Places like Brandenburg (1540) kept the full palm rite but omitted the consecration of the palms. In 1589, Matthäus Ludecus, dean of the Lutheran cathedral of Havelberg, criticized the palm procession (he’d inherited an elaborate one) but provided most of the music for it as well as three settings of St. Matthew’s Passion.

However, places like Magdeburg, in the 1613 Cathedral Book (similar to our Altar Book), appoints simply the triumphal entry account for Palm Sunday. There’s no reading of the Passion. The Lutheran Hymnal (TLH, 1941) followed that tradition. It should be noted, though, that in the Holy Week 1963 issue of the early liturgical journal, Una Sancta, the more ancient Palm Sunday celebration (as well the more historic rites for Good Friday and the Easter Vigil) was (re?)introduced to large sections of American Lutheranism.

But no matter how you celebrate Palm Sunday, what everyone agrees on is the singing of “All Glory, Laud, and Honor,” (LSB 442). This hymn has been part of the Palm Sunday liturgy since the ninth century. Written by Theodulf (d. c. 821), bishop of Orléans, legend holds that he’d fallen out of favor with the emperor and was imprisoned. As he heard the palm procession pass by the prison, he began singing his hymn. It so impressed the emperor that he had Theodulf released and restored to his position, requesting that the hymn be sung during the palm procession every year. The emperor’s request has been met ever since.

Misnomers

Perhaps something should be said about the unfortunate misnomer of Palm Sunday as “The Sunday of the Passion.” That is a recent development. As already mentioned, Palm Sunday has been “Palm Sunday” since the fifth century. Yes, the Passion is read, but the day is named for the palm ceremony and the triumphal entry. Historically, “Passion Sunday” was the Sunday before Palm Sunday, known in the one-year lectionary as Judica. Whereas the preceding Sundays in Lent are catechetical in nature about what it means to be baptized into Christ, Judica begins the final two-week journey where our focus shifts especially to Jesus’ physical sufferings for our sake as the plots and threats against Him rise. Palm Sunday, then, begins Holy Week, still part of Passiontide, where that suffering reaches its fulfillment, as the plot is carried out and Jesus sheds His blood to win our salvation. This is triumph.

So, what does this mean? The LSB Palm Sunday rite — with procession and the Passion — has just as much Lutheran history and precedent as TLH’s “just” Palm Sunday. It’s also commended to us by the majority of Christian history. So, if your pastor uses this rite, rest assured he’s not doing something weird or strange; he’s not following after Vatican II, or covering all his bases, or accommodating those inclined to skip Maundy Thursday or Good Friday. What LSB offers is the Western Church’s tradition of about 1,600 years, which has fed and nourished Christians in times of plague, war, fear, unrest and also in times of peace.

Receive the gifts

In fact, if your church offers the Divine Service or even the Daily Offices for Holy Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, I encourage you to attend those as well. And, if not, ask your pastor about it. Yes, you will hear all four Passion accounts — Matthew on Sunday, Mark on Tuesday, Luke on Wednesday and John on Friday. You’ll also hear the writings of the prophets looking forward to these things. You’ll hear the preaching of the Apostles ruminating on the fulfillment of these things and the gifts thereby given. You will hear an abundance of Holy Scripture gloriously woven together. You will hear the fullness of the Lord Jesus’ suffering and death, recounted by each of the holy evangelists with their specific emphases, whereby He rescues us from sin, death and the devil.

Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is He who comes in the Name of the Lord!

Probably like many I was raised on TLH 5/15 along with Matins and Vespers. The change to LSB was rather abrupt and it took me some time to acquire familiarity with the melodies and chants in the liturgy. Now I would likely consider TLH to be too limited.

I appreciate the scripture references in the liturgy, historical notations, its richness, and the obvious care that was taken to put the LSB together. Not to take anything away from TLH, of course! I am ever thankful that we have been given the LSB.

This is excellent work. Pastor Stephens, thank you.

In your final full paragraph, it should read that the Passion account according to Saint Matthew is heard on Holy Monday, not “Sunday.”

Sorry, you’re mistaken. Look again. Though apparently there’s an option to repeat it on Holy Monday, but the alternate option is John 12:1-23.

I am very grateful for the history lesson. Thank you Pastor Stephens!