How Luther’s colleague helped spread the Gospel message to the four corners of the world.

Martin Luther’s insights into Holy Scripture sparked a Reformation, but the sparks would not have spread the fire of reform beyond his own circles in university and cloister if they had not also ignited a team who helped to spread his teaching. Printers and artists produced the literature that carried the thinking of Luther and his colleagues across Europe. Princes and courtiers provided political structures, social support and military protection for the introduction and growth of Luther’s understanding of the message of salvation in Jesus Christ. Preachers from towns and villages across German-speaking lands delivered the message and cultivated faith in their own locales. A key player in this team was Johannes Bugenhagen.

Luther’s colleagues in Wittenberg’s theological faculty formed the nucleus of his team. Alongside Philip Melanchthon, these included Justus Jonas, Caspar Cruciger the Elder and Bugenhagen. The five not only taught together. They talked together and traded ideas. Their families enjoyed life together. Their children played together. They functioned as a team.

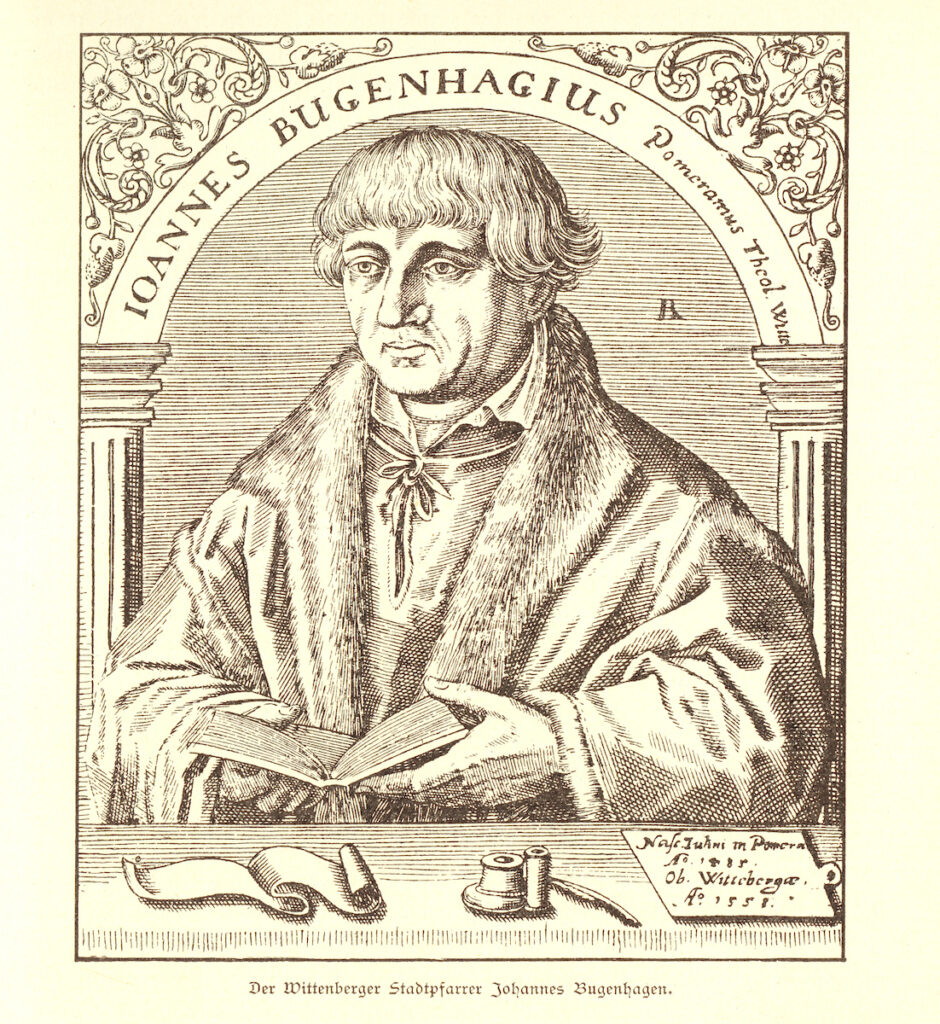

Pomeranus

Bugenhagen, who died April 20, 1558, two months short of his 73rd birthday, bore the nickname “Pomeranus” because he came from the duchy of Pomerania on the Baltic Sea coast. After studying at the Pomeranian university in Greifswald, he became a school rector and then an instructor at a monastic school for priests. His interest in the reform of the church, fired by the works of Desiderius Erasmus, led him to read the early works of Luther. Particularly the reformer’s Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church of 1520 impressed him. In 1521 he left Pomerania to begin study in Wittenberg. At first he lived in the home of Philip Melanchthon.

Melanchthon and Luther soon asked him to lecture at the university. The three did not always agree. Luther came to accept Melanchthon’s reasoning that Christ’s descent into hell was a part of His exaltation, but Bugenhagen argued further for the descent being the culmination of His suffering and humiliation. Such differences did not interrupt their common efforts in spreading the word of Christ’s promise of new life for sinners.

In 1522 Bugenhagen married. With his wife Walpurga, he had four children who survived infancy. Their son, Johannes Junior, followed his father as a professor at the university. The Bugenhagen household, like Luther’s and Melanchthon’s, included other relatives and a number of students. Guests from near and far also enjoyed the hospitality of their home on the plaza surrounding the church of Saint Mary, Wittenberg’s town church.

Around this time Bugenhagen began to give instruction at the university. Luther had concentrated his lectures on biblical books, abandoning lectures on extrabiblical works. Bugenhagen followed Luther’s example. He lectured on a wide range of the Scriptures, both Old Testament and New Testament, for over three decades, finally retiring in 1556 as his health began to fail.

In 1523 Bugenhagen became pastor of the Wittenberg church. His preaching provided a model for students as well as edification for the residents of the town for 35 years. His staff included several deacons or assistant pastors over the years, a kind of vicarage long before the invention of the concept of vicarage. He heard private confessions, visited the sick and dying, conducted funerals and marriage services. Marriage officially took place as a civil action, but the Reformation introduced the sermon within a marriage service alongside the civil ceremony. Bugenhagen preached for Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora when they wed, and he preached a sermon as Luther was buried in Wittenberg two decades later.

Spreading the Reformation

The churches of the German-speaking lands needed reorganization as they departed from the medieval model centered on the rituals of the mass and related ceremonies and practices. Local priests, in this model, governed the access of the people to God under the guidance of bishops and pope. Luther’s Gospel taught believers that God comes first to them speaking through His Word. His promise of new life in Christ frees them from their sins, so that they can freely practice their gift of being human creatures as God designed them.

Putting Luther’s teaching into practice meant, first of all, that local priests became preachers and pastors, proclaiming God’s Word and shepherding His people. Bugenhagen took the lead in aiding churches to reshape their ecclesiastical life in accord with Scripture. In 1524 he sent written instructions to the church in the city of Hamburg on how to remodel the practices of the Christian community there. Beginning in 1528, he began to travel, carrying out this task in other lands. His sojourn in Denmark lasted almost two years; his stamp remains on the Danish church to this day. He spent shorter amounts of time in his home duchy of Pomerania and in a number of towns, including Braunschweig, Hamburg and Lübeck. Bugenhagen listened to the local leaders to design specific forms for worship, social welfare, education and related matters of the practice of the faith in those specific places.

Bugenhagen served the church of Electoral Saxony as well. He became its first “superintendent” (administrator of spiritual affairs), replacing the papally loyal bishops who opposed the introduction of reforms. In the 1520s and 1530s the bishops, in their loyalty to the Roman papacy, refused to ordain Wittenberg graduates in most cases. It was taught that ordination could only be dispensed by a bishop. For more than a decade, then, the Wittenberg professors sent out their students to become pastors without ordination. Finally, in 1533, the Saxons decided to have Bugenhagen ordain those being sent to pastoral positions. Not only Saxon shepherds but others from Transylvania to Finland, from the Rhineland in the west to Austria in the south, carried the Wittenberg message under the blessing of pastor and professor Bugenhagen.

Bugenhagen was concerned for the priests across central Europe whose education, often limited to a few semesters at a university or secondary school, had focused on the dogmatic texts of Peter Lombard, without preparation for their new task of preaching on the basis of Scripture. Furthermore, many students moved through Wittenberg’s biblically based curriculum quickly, sent out to congregations with only a few semesters of education. In the 1520s the Wittenberg professors, with a few disciples, produced what Timothy Wengert has called “the Wittenberg Commentary,” a series of introductory treatments of New Testament books. Bugenhagen provided notes on 10 Pauline epistles (from Galatians through Philemon), plus Hebrews. He also wrote commentaries on the Gospels of Matthew, Luke and John and added one on 1 and 2 Corinthians. The Old Testament also commanded his interest. Commentaries on Job, Isaiah, Deuteronomy, 1 and 2 Samuel, Jeremiah and Jonah flowed from his pen over the years. His expositions were brief, aimed at pastors who needed to expand their understanding of the biblical story and teaching. Some of his commentaries used Luther’s prefaces to the biblical books to introduce the work, and some incorporated topics from Melanchthon’s handbook for teaching the faith, the Loci communes. Wittenberg theologians published as a team.

Bugenhagen pioneered the Wittenberg creation of “harmonies” which integrated the accounts of Christ’s passion, death and resurrection from the four Gospels. This first harmony account appeared in Latin in 1524 and within seven years had been translated into both High and German and Low German. This literary genre became standard reading for Passion Week in churches across the German-speaking lands and beyond.

In the 16th century intellectuals across Europe spoke Latin. In order to spread the Wittenberg message, Bugenhagen’s colleague Justus Jonas served as translator of certain works of Luther and of Melanchthon from Latin into German or German into Latin. But this was not the only language barrier the Wittenberg theologians faced. Within the German-speaking lands, which extended beyond the political boundaries of the German or Holy Roman Empire, a number of dialects, some hardly understandable to those born in other territories, served populations in various areas. Bugenhagen grew up speaking Low German, quite different from the High German that was developing at the time, in part aided by Luther’s use of it in his translation of the Bible. Bugenhagen’s rendering of countless works, including the Wittenberg translation of the Bible, into Low German built bridges into the north German cultures that spoke that language.

A preacher of Christ

Manuscripts remain of Bugenhagen’s sermons on the catechism from 1525 and 1532, delivered for the children and youth of Wittenberg in Sunday afternoon catechetical services. Bugenhagen’s explanations demonstrate how closely the Wittenberg professors worked together, for some of his expressions in 1525 found their way into Luther’s catechisms four years later. In 1532, the preacher sketched the plan of the catechism as Luther had set it forth in his Prayer Book of 1522: “First, you hear from the Decalogue what you are to do. Second, you hear in the Creed of the one in whom you put your trust. Third, you learn what is required of you.” In 1525 Bugenhagen had explained the First Commandment with words that Luther echoed in his Large Catechism. “God is the one in whom a person trusts, who gives everything and cares for us in every way, as parents care for their children.” Using Jesus’ statement in John 3 that we must be born again, he reminded his hearers that “the child has not earned anything, but the father provides for it.”

Bugenhagen’s sermons exalted Christ and placed Him at the center of his hearers’ lives. That “Jesus is Lord,” he preached in 1525, means that He is our “head, king, priest, one whom we do not merely know but who reigns in our thinking against every other power.” In 1532, Bugenhagen proclaimed Christ as “our Lord, who rules and defends us against Satan, human traditions, hell, sin, and death, [and they] shall not rule over this Lord.” Repeating Luther’s words from his 1531 Galatians lectures, Bugenhagen proclaimed that Jesus became a sinner who bore the sins of the world, so that those who trust in Him might be free from sin and guilt. He satisfied the law’s demand for the death of the sinner, and through His resurrection and place at God’s right hand, He took away our sin and defends us against all evils. After His resurrection Jesus sent the Holy Spirit, who forgives sins and delivers to the faithful grace and enlightenment from God. Bugenhagen proclaimed all this to his hearers.

Through all the turmoil that afflicted the University of Wittenberg and the Saxon church in Bugenhagen’s later years, he continued to preach Christ crucified and risen as he shaped his students’ thinking and proclamation. He built upon and spread the message of his Wittenberg colleagues all over central Europe, through his presence in Denmark and several German towns and principalities, through his many writings and through his instruction of students. Without Luther, Bugenhagen might have fought for reform in the church but would not have grasped the Gospel promise of forgiveness, life and salvation in Christ. Without Bugenhagen, Luther would not have formed the thoughts and lives of people from the 16th century to the 21st, from Wittenberg to the four corners of the world.

Header Photo: LCMS Communications/Erik M. Lunsford

It should also be mentioned Bugenhagen’s designing pure Lutheran liturgies as a significant means of extending the Reformation to especially the northern European countries.