By Eric Andræ

“All these things Jesus said to the crowds in parables; indeed, he said nothing to them without a parable" (Matt. 13:34).

When I was in my first year at Concordia Seminary in the fall of 1993, some in my class questioned why a novel would be required reading for students of theology. Although we all came to appreciate — actually, love — Bo Giertz’s famous The Hammer of God, at first some wondered why pupils of truth and doctrine would need to read fiction.

So then, why should they? Why should you?

In addition to conveying ideas, concepts, and feelings, novels supplement and enhance academic talk about these same matters; that is, novels manifest theology, dogma and doctrine by illustration, information, incarnation and identification. The divine drama is enfleshed among and for God’s people — and for the world — when we tell stories. In this way, may we perhaps assert that fiction can be a means of grace?

The Hammer of God (1941) follows three pastors and various members of the same parish in southern Sweden over three different generations. Swedish scholar Anders Jarlert has argued that this novel serves as illustration, verification, and incarnation of Giertz’s Lutheran theology. Giertz’s novel illustrates how conversion happens within the historical settings of the church’s life. It verifies the doctrine of justification by grace alone through faith alone. And it serves as an incarnation — a human enfleshment, if you will — of Giertz’s earlier dogmatic work, chiefly his first book Christ’s Church (1939) and his second, Churchly Piety (1939).[1] Taken together with these, Giertz’s novel comprises the third part of a sort of theological trilogy.

Giertz claimed that for “modern man to understand [grace, Law and Gospel, conversion, justification and sanctification], it is necessary to illustrate it among people of flesh and blood.” Giertz does the same, albeit in different ways, with his subsequent novels, The Knights of Rhodes (1972) and especially the acclaimed Faith Alone (1943), forming another kind of trilogy.

Katie Schuermann, well known to readers of The Lutheran Witness, calls Giertz “Lutheranism’s greatest storyteller.” Her novels display the influence of Giertz in many ways — most especially her latest novel, The Saints of Whistle Grove (2023).

As in The Hammer of God, in The Saints of Whistle Grove the setting (the land and locale in the heartland of each nation) remains the same across the many generations, although the people change. However, while Giertz tells his stories chronologically, Schuermann’s narrative is asynchronous, grouping the tales together within the community’s grove, church, school, and cemetery — and it is significant that, as in Giertz’s native Sweden, the graveyard is immediately adjacent to the church.

There are other small particulars that manifest the similarities: Both authors have an eye for nature’s details and import; an abiding, warm, almost romantic, love for the church; pastoral protagonists who sometimes need the guidance or respectful reprimand of their sheep; prominent female heroines often stronger than their male counterparts; the crucial use of personal letters, sometimes received posthumously. Both writers are adept at describing characters in brief prose, so that we can quickly but truly get to know them, while also being sympathetic to those of various personalities and shortcomings.

Like Giertz, Schuermann illustrates, informs and enfleshes.

Through its pages and people, its stories and saints, its chapters and characters, The Saints of Whistle Grove illustrates how death and mourning, hope and resurrection are experienced throughout several generations of five families in one parish from 1866 to the modern day, and how these realities might even change hearts and minds well beyond the walls and membership roll of Bethlehem Lutheran Church.

As such, Schuermann also informs the reader of the church’s doctrine. Indeed, the attestation and verification of many biblical teachings find a home in the homes and lives of the Lord’s flock in Whistle Grove — sin and grace, the problem of evil, the sanctity of the body, vocation, sexuality, confession and absolution, liturgy, sanctification and more. Especially prominent is the indissoluble relationship between the Body of Christ and the bodies of the quick and the dead, the saints militant and the saints triumphant.

This incarnation of the church’s dogma finds repeated, and often powerfully moving, expression in the author’s main theme of continuity. The ongoing reality of eternity is dramatized: even when physical steeples are falling, spires crumbling, and church buildings closing, the permanence of the church’s presence continues through her ministry of Word and Sacrament and through her baptized priests’ prayers and selfless service.

And it is these saints in Christ — who are also very much sinners — with whom we can also identify. Both Giertz and Schuermann describe the human condition, communicate their characters’ contexts and the people’s personalities in such a way that, by the grace of God, the reader might exclaim: “There go I! This is for me.”

Good fiction can place the reader into the story in a way that history or news or even systematic theology cannot. Such identification — which is perhaps a novel’s chief strength — is not really possible in those other formats. After all, I know that I am not those historical or contemporary figures, and I am not simply a doctrine either; rather I am a person of flesh and blood, a human of experience and emotions, of hopes and dreams.

So, in what might at first seem a counterintuitive claim, a novel can move us from theory to practice, from the general to the specific, from the abstract to the concrete. Literature like The Hammer of God and The Saints of Whistle Grove can help us to see the timeless truths of the Gospel from a different perspective, to the see the ancient truth with new (others’) eyes, to hear the timeless message through the fresh ears of the fellow and yet fictional faithful, with all their strengths and weaknesses which are also so often ours.

As a matter of fact, literature can serve this role of identification even, perhaps especially, when the reader is not fully aware of certain aspects of his or her own experience, of self. A novel can help you discover truths about the world and your place in it of which you had perhaps an inkling, but were not fully conscious. Walker Percy puts it this way: “In art, whether it’s poetry, fiction or painting, you are telling the reader or listener or viewer something he already knows but which he doesn’t quite know that he knows, so that in the action of communication he experiences a recognition, a feeling that he has been there before, a shock of recognition.”

So, fiction as a means of grace? Yes, insofar as it “enfleshes” the Gospel, of course!

In fact, perhaps the strongest argument for writing and reading fiction with intentional Christian themes and Gospel patterns is that this is how our Lord himself taught! Jesus used over 50 parables or parabolic sayings to instruct his hearers. And so we, too, declare the Gospel in multiple ways — preaching, teaching, reaching out, sharing, defending, caring, listening, and, yes, telling stories.

Giertz and Schuermann, specifically and intentionally Lutheran authors, know the means of grace; they know grace; indeed, they know and write sola gratia, grace alone.

So, dear reader, definitely read and meditate upon Scripture; certainly read and sing the church’s hymnody; surely read and pray her prayers. But read also Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Greene, Lewis, Tolkien, Steinbeck, Waugh, O’Connor, Berry, and Percy, as well as Bo Giertz and Katie Schuermann.

Recommendations for further reading and learning:

- Francis Rossow, Gospel Patterns in Literature: Familiar Truths in Unexpected Places (2008) and “Echoes of the Gospel-event in Literature and Elsewhere” (Concordia Journal, March 1983) — My love for the connections between fiction and faith owes perhaps its greatest debt of gratitude to “Rev” Rossow, whose class “Literature and the Gospel” during my seminary days in 1997 has ever since inspired.

- Donald Deffner, “The Paperback in the Pew” (Concordia Theological Monthly, 1961)

- Gene Veith, Reading Between the Lines: A Christian Guide to Literature (1990, 2013) — Rossow recommends this book, by another author who will be well known to the readers of The Lutheran Witness.

- Leland Ryken, Philip Ryken, and Todd Wilson, Pastors in the Classics: Timeless Lessons on Life and Ministry from World Literature (2012). With a focus on the Office of the Ministry, these evangelical academics from Wheaton College provide a helpful exploration.

- More specific to Giertz, Veith has an essay “Fiction as an Instrument for the Gospel” in A Hammer for God: Bo Giertz – Lectures and from the Centennial Symposia and Selected Essays by the Bishop (2010). Unfortunately this book is currently out of print, but you can contact me for Veith’s article or the book as a whole.

- You can also read my paper on The Hammer of God, “‘The best treatment of the proper distinction of law and gospel in the history of Lutheran theology:’ A Historical and Systematic Overview” in Lutheran Theological Review (2012).

- Finally, join me in Seattle in June for a continuing education course on Giertz which will engage his fiction and much, much more!

[1] I am currently undertaking a translation of this second work, which has never before appeared in English.

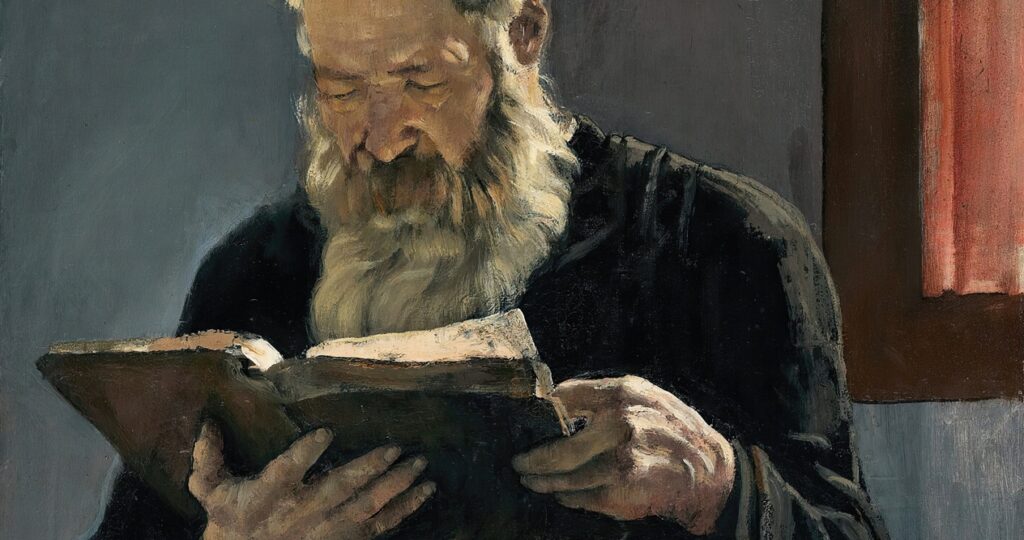

Image: “Reading Priest,” Ferdinand Hodler, 1853-1918.