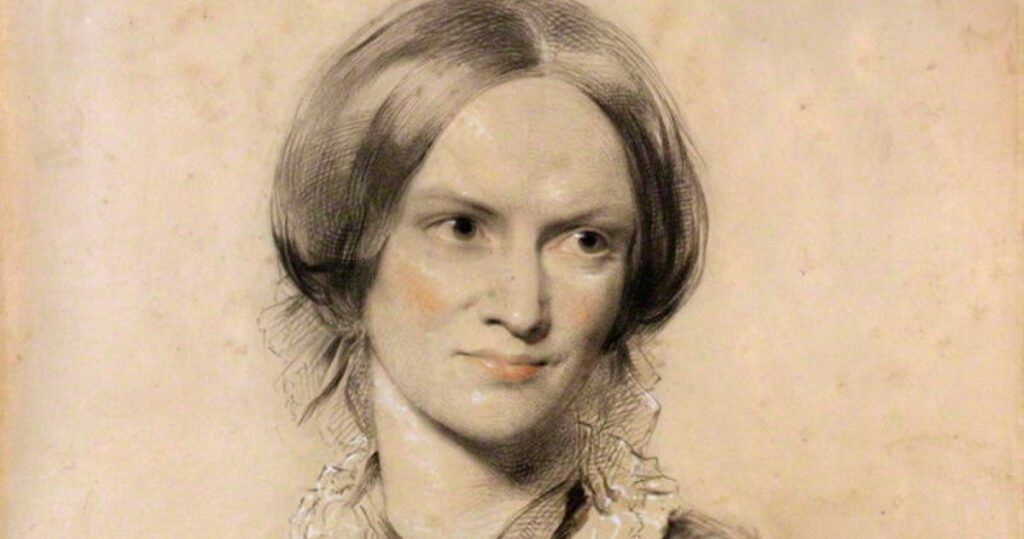

A literary reflection by Kevin Martin on C.S. Lewis's "That Hideous Strength." This is one installment of a monthly series providing reflections on works of literature from a Lutheran perspective.

That Hideous Strength, the final volume of C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy, has gotten much attention even in the secular press lately for its prescience in seeing, back in the early 1940s, how fast a culture that turns against Christianity also moves towards abolishing humanity and the virtues.

The book is set in early post-WWII England (though Lewis wrote most of the book before the war ended). It depicts a fictional battle waged against the National Institute of Coordinated Experiments (“N.I.C.E”) by a little “company” led by Elwin Ransom — a character who has visited Mars and Venus in the first two volumes of the trilogy, and who is modeled after both Lewis himself and his friend J.R.R. Tolkien.

I’ve always been delighted with the company that gathers around Ransom at St. Anne’s on the Hill as an image of the first Christian community. It’s a small and eclectic group of seven (later eight when Merlin the Magician joins them) people who have fled for refuge in great distress to Ransom’s company.

This company’s bond is simple devotion to Maleldil (an early version of Aslan, a Christ-figure). Ransom seems a St. Peter figure, whose faith has miraculously transformed him, like Elijah or Enoch, into someone who is ready to walk with God, skipping death.

In Chapter 7, a woman named Jane Studdock (a “seer”) meets Ransom and comes under his company’s marvelous influence. Jane is estranged from her husband (they’ve only recently wed) and is initially attracted to Ransom, who stifles such feelings quickly. We come to see, as readers, what Jane does not: that it is the quality of holiness that draws her to Ransom. This love of holiness and purity begins a transformation of Jane’s love for her husband that will result in their reconciliation and happiness. It also results in Jane’s coming to faith.

Jane’s belief in Ransom’s “Masters” (the Triune God?) isn’t initially rational or emotional; it is a love for holiness that results in faith. She ultimately realizes that Ransom is good and true because his Master is the Lord of heaven and earth — Creator, Redeemer and Sanctifier. It has always seemed to me a lovely picture of faith in Christ Jesus and how the Holy Spirit draws us (in ways we can’t quite articulate!) into a company of other servants of Christ that transforms our lives and our loves profoundly, so much so that we’d brave any danger or hazard, even face death rather than fall away from this inspired-and-inspiring company.

Also striking is the purpose of Ransom’s community. They are very much a secret society — as the first Christian community was, in a world that would think nothing of eradicating them if their true nature should be revealed. Rather than being “missional” as most of Christendom thinks we ought to be, seeking to convert outsiders to the faith by any means necessary, this company is on a mission. They are like a commando group caught behind enemy lines trying to throw a few wrenches into the demonic lies and murder that make a horror of God’s world; if they are caught or killed, they’ll count themselves fortunate to have suffered shame for the sake of the Name, just like the apostles in Acts 5.

It is their inchoate faith in the Master and devotion to the fellowship of a “Mr. Fisher-King” (Ransom’s adopted name which recalls both Christ and Peter the fisherman-prince of the Apostles) that makes the whole company brave, truthful, faithful, joyful. And the quite unlikely victory that ensues is a mere side benefit, not the thing at which they were aiming, which seems to have been only this: Don’t let our side down! Because it’s the good side!

Lewis powerfully and delightfully imagines the sort of faith that animated the first Christian community and what it might look like in the modern world. When Jane meets Ransom, she at first wants to abandon her difficult and dull life with Mark in the world to come hide out at St. Anne’s on the Hill. But Ransom cannot allow this. It would not be right and fitting for a married woman to forsake her duties to her earthly community and husband. Jane bristles at this at first, but realizes she is actually quite happy, joyful even, talking to Ransom and then traveling back to her home, noticing all sorts of beauty in the everyday ordinary she’d previously missed.

Eventually, after Jane gets caught in a riot and is tortured by the N.I.C.E.’s secret police (which isn’t “nice” at all!), she escapes to St. Anne’s on the Hill. But being part of the community at St. Anne’s only plunges Jane and the others more deeply into their vocations and callings in an increasingly dangerous and hostile world. Though it’s tempting to adopt the lawless, loveless, self-interested hate of their enemies, Ransom shows this is not Maleldil’s Way, and so it cannot be theirs. Ransom’s company increasingly eschews self-interest and the utilitarian for the good, the true, and the beautiful — even when that course seems foolish, fruitless and futile.

Jane starts by wanting to please Ransom, but soon realizes he’s only out to please his Master, Maleldil. To me, this is the chief attraction of Lewis’ book: watching how the lovers of God come to love one another, seeing their self-concern get replaced by concern for what pleases the Master. This in turn leads them not to withdraw from a hostile world, but instead willingly, joyfully, to risk all to save it.

In one scene, Jane awakens at the Manor at St. Anne’s after being captured, tortured, interrogated, and caught in the midst of a riot. Lewis writes, “Long after sunrise there came into Jane’s sleeping mind a sensation which, had she put it into words, would have sung, ‘Be glad thou sleeper and thy sorrow offcast. I am the gate to all good adventure.’”

This is what Christian community is: the gate to all good adventure. The first Christian community did not fade away with the first century, but, indeed, is the very one in which we still dwell, by Christ Jesus’ grace and mercy, in the fellowship of the apostles, the breaking of bread, and the prayers. Under the modest, even ramshackle exterior of your local congregation, Christ Himself awaits — drawing you into His good adventure.

The Fisher King is a character in Mallory’s Morte D’Artur.

The author claims that “most of Christendom thinks we ought to be … seeking to convert outsiders to the faith by any means necessary.” How has the prevalence of that belief been assessed?

Whatever the prevailing belief today, the Bible gives compelling reasons to adapt practices and forgo preferences out of love for the lost:

• Jesus said, “[T]here will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance” (Luke 15:7 ESV).

• Jesus took a different form to save us: “Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant” (Phil 2:5-7).

• Paul adapted to better relate to people with the Gospel: “I have made myself a servant to all, that I might win more of them. […] I have become all things to all people, that by all means I might save some” (1 Cor. 9:19, 22).

• The early Christian church was called upon to adapt their worship for the sake of “outsiders or unbelievers” (1 Cor. 14:23-25).

I think That Hideous Strength is a pretty good book (though not as good as the first two). Lewis made some good points in it, although I think it’s hilarious when Ransom, a lifelong bachelor written by a another (then) lifelong bachelor confidently tells Jane how to fix her marriage. But I find Pastor Martin’s comparison of Ransom’s “company” to the early church rather strange. The early church was not a secret society–they welcomed all and proclaimed the Gospel to all very publicly. And what is wrong with being “missional”? Didn’t Jesus tell us to share the Gospel and make disciples of all nations (the Great Commission)?