By Natalie Nieminen

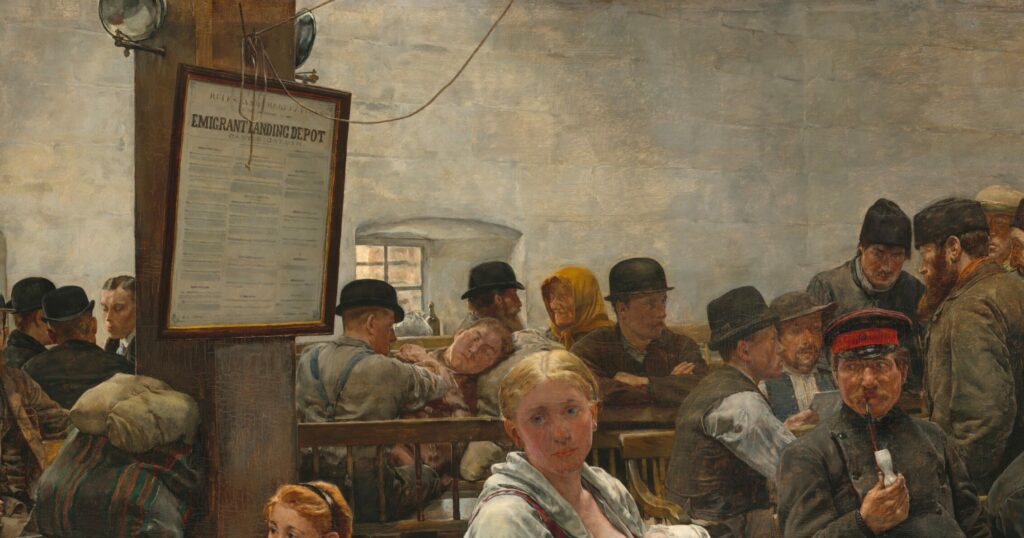

Upon landing in New York, 19th century German immigrants faced many hardships. But God transformed their suffering into hope through the work of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod and its immigrant mission.

A treacherous journey, a treacherous arrival

In the 1800s, the poorest immigrants sailed in steerage — cramped quarters on beds of straw in the helm of the ship — where they endured a harrowing, nauseating journey with little fresh air. After two weeks at sea, relief washed over them as they arrived in America, hoping for a better life in the Land of the Free.

But New York’s Castle Garden[1] was no Garden of Eden.

Settling in America was not as easy as stepping foot on American soil. Some discovered that the fees to travel to the interior of the country cost more than their budgets allowed. Scoundrels plundered many new arrivals through all kinds of deceit. Counterfeiters sold fake train tickets or exchanged money for worthless paper. Often, couriers purposely delivered luggage to the wrong address, returning possessions only through extortion. Unclaimed children, sponsored by relatives, wandered the corridors of the vast hall of Castle Garden alone, with no one to show them the way. Immigrants usually had no connections — no friends or family in the country to whom they could turn for help.

In addition to their families and homes, these immigrants had left behind their churches. A Lutheran pastor in New York, Rev. F. W. Föhlinger, described the situation in an article in Der Lutheraner, the nascent Missouri Synod’s official newspaper, in 1867:“Many completely lose the last weak thread tying them to their home church. Some become prey to the sects that greedily grab at them. Others sink into such a worldly mentality with such indifference that they seek neither church nor school and seek only their own survival and earthly happiness.”[i]

A new immigrant mission

Missouri Synod Lutheran congregations in New York brought the plight of these sojourners to the Synod convention of 1867 with a motion to begin an immigrant mission. Individuals opposed with many objections. One feared charity would welcome idle crooks into Lutheran communities. Another worried costs would be insurmountable. Dissenters assuaged their consciences with assertions that other denominations already served immigrants and that secular institutions relieved the church of her burden.

Rev. Föhlinger exhorted against these poor excuses, reminding hearers of the Good Samaritan. Among other verses, he quoted 1 John 3:17, “But if anyone has the world’s goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him, how does God’s love abide in him?”

In the end, congregations voted in support of an immigrant mission and established an immigrant committee. Rev. Stephanus Keyl[2] was called as missionary. Since his mission ventured into uncertain territory, Rev. Keyl was given a broad task: helping the newcomers wherever they had need.

Rev. Keyl helped buy tickets, exchange money and transport luggage. He acted as translator for those who didn’t speak English. He assisted young travelers so they arrived safely at their final destination. For those who lacked travel funds, he advanced money when it was available.

He encountered many obstacles.

In his report of 1870, Rev. Keyl said, “Some of my interactions have been so difficult that I’m surprised I’m still alive. Some immigrants did not carefully follow my advice and were defrauded. They took their grievances against me to the press. They filed lawsuits against me. Almost everyone in Castle Garden regards missionaries as a tolerated evil, and we are treated accordingly.”[ii]

Meanwhile, money only trickled into the mission fund, while immigrants flooded into the country.

The immigrant committee appealed for more donations in Der Lutheraner. They circuited congregations, informing them of the important work provided by the mission, suggesting ways to help. Rev. Keyl sailed to Germany and formed relationships with pastors and emigration agents in Hamburg and Bremen, the two largest German ports.

Word spread about the good work provided by the immigrant mission. Money began flowing faster.

The harvest was plentiful. The laborers were few.

‘The watchmen on the walls’

Seeing a void, pastors in the Synod provided Rev. Keyl with papers to distribute when a ship arrived. Pastor Adam Ernst, head of the Canada District, sent crates of the newspaper Lutherisches Volksblatt[3] for free distribution. Rev. P. Beyer in Chicago wrote a tract especially for the mission. These papers received a warm reception in Castle Garden.

Assisting immigrants physically opened the door for Rev. Keyl to share the Gospel. He reminded Christians that suffering produces endurance, endurance produces character, and character produces hope. For the spiritually starving, God’s Word provided food for the soul.

Yet, faith was in danger of withering if the immigrants, upon settling, were not churched. Rev. Keyl wrote in his 1878 report: “The watchmen on the walls of our Lutheran Zion have been sleeping, and sectarianism and unbelief have reaped a terrible harvest among our Lutheran Christians. What sincere Lutheran does not weep for the slain among his people and mourn the fact that his church, compared to other church communities in this country, stands like a little cottage in the vineyard, like a hut in a Turkish garden, like a devastated city! If this seems exaggerated, come to the east coast and examine the small number of Lutheran congregations in the cities and in the countryside, many of which are still eking out a miserable existence. But what a mass of German Lutherans have immigrated here for 200 years! Where are their descendants?[iii]”

To encourage settling in established Lutheran communities, employers sent Rev. Keyl travel money for immigrants to move to their cities, with the guarantee of a job. The LCMS published a devotional calendar listing all Lutheran pastors and congregations in North America. Those still deciding where they would settle could select a city from the listing where they would be served spiritually. Through donations, congregations sponsored immigrants. Immigrants, once settled, supported congregations.

Through the acts of the immigrant missionary, sometimes small and seemingly insignificant, the Lord fulfilled His promise to watch over the sojourner. Through pastoral care, Lutheran immigrants learned that they were not merely Germans going to America with earthly hopes and dreams, but citizens of heaven, sojourning on earth with heavenly hope.

[1] Castle Garden was located within Battery Park, New York. It predated Ellis Island, and served as America’s largest immigrant processing facility from 1855–1892.

[2] Stephanus Keyl was son of Rev. E. G. W. Keyl. He was also nephew and son-in-law to Rev. Dr. C. F. W. Walther.

[3] Lutherisches Volksblatt was a Canadian paper similar to C. F. W. Walther’s Der Lutheraner.

[i] Der Lutheraner XXIV (1 12 1867), 50.

[ii] Der Lutheraner XXVI (1 5 1870), 134.

[iii] Der Lutheraner XXXIV (1 3 1878), 33.

Image: “In the Land of Promise: Castle Garen” by Charles Frederic Ulrich, 1884.

This article was informative and easy to understand. As one who loves digging into family history, already knowing about Castle Garden where many think only of Ellis Island, I enjoyed it very much and hope you will continue to share your knowledge in such an accessible way. It is something the whole family can read and we can discuss together. I wanted to hear more. “Where are there descendants?”, struck me as not much different from today, which gives hope. God has a plan for every generation. Well done.

RE: “Through pastoral care, Lutheran immigrants learned that they were … citizens of heaven, sojourning on earth with heavenly hope.”

Wouldn’t most Lutheran immigrants have understood that before they crossed the Atlantic?