By Robert Dargatz

There are still many people who were at our seminaries 50 years ago when the events at the seminary in St. Louis — culminating in what is known as “the Walkout” — made a huge impact on the LCMS. These events dramatically affected our church body and American Lutheranism, and most especially the lives of the professors and seminarians of both the St. Louis and Springfield seminaries and all the Concordias.

I was a student at the Springfield seminary from 1972 to 1976 (the last year of operation on the Springfield campus). Please allow a Springfield seminarian of that era to add observations regarding the impact of the crisis in St. Louis upon “the other seminary” during the middle of the 1970s.

Having two seminaries to prepare men for the ministry of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod was questioned at various times in the life of the Synod. Was it an unnecessary expense that was inefficient and poor stewardship? In the 1970s, it proved to be the blessing that certain organizations find in intentional redundancy. If there had been only one seminary in 1974, the Synod would have been virtually forced to capitulate to the vision of that seminary’s president and faculty.

The Springfield seminary had served primarily to provide an avenue for second career men moved by the Holy Spirit to enter ordained ministry. It did not require (or, at times, even offer) Hebrew. The student body was older, many of them married and with young children. They came from all over the Synod and represented something of the diversity of the Synod at that time. In 1962 at the end of a short but significant presidency of George Beto, the Springfield seminary committed itself to work toward the new standard of only admitting incoming students who had a college degree. That was also the beginning of the presidency of J. A. O. Preus, who had been on the faculty since 1958.

By 1965 the student body of Springfield could boast of having students from a hundred different universities and colleges. In 1967 the Synodical convention held in New York passed a resolution allowing graduates of Concordia Senior College to choose to attend the Springfield seminary instead of the one in St. Louis if they chose to do so. A significant number of these students exercised this option. The Senior College had been designed to send students to the St. Louis seminary. Most, but not all, of the Senior College’s faculty were supportive of what was going on at the St. Louis seminary. A number of them helped to recruit their students for St. Louis as opposed to Springfield.

A more subtle example of this tendency may be illustrated by an announcement in the Senior College’s daily bulletin that was published when recruiters from Springfield made a visit to that campus in 1971: “Recruiters from a seminary will be on campus this morning and available to speak to interested students after chapel.” Some “confessional” students that had already determined to go to Springfield wryly remarked that if Springfield was “a” seminary, St. Louis must be the “b” seminary. Several years later, after the Walkout, when the 1975 LCMS convention determined to close the Senior College, the major reason was that many faculty members were encouraging students to enroll at Seminex.

John Tietjen was elected to be the president of Concordia Seminary in St. Louis on May 19, 1969, shortly before J. A. O. Preus was elected Synod president at the Denver convention. Some think that Tietjen was put into office shortly before the convention because it was anticipated that there might be changes in key positions in the Synod that would affect who would make up the four electors of the president of the seminary. That anticipation proved to be accurate. It also caused the necessity of the election of a new president of the Springfield seminary which Dr. Preus had to vacate in order to accept the position of Synod president. Lorman Petersen was elevated from academic dean to acting president.

Petersen was thought by many to be a front-runner for being elected as Springfield’s next president, but instead, to the surprise of many, Richard Schultz was named president. Schultz had been called to the Springfield faculty four years earlier to teach classes like parish education in the practical department (compared to Petersen who had been on the faculty for twenty years). Schultz had Petersen return to his role as academic dean and the two of them were determined to work closely with the seminary in St. Louis. Dr. Petersen exercised significant authority in regard to curriculum, teaching assignments, and the calling of new faculty. Twelve additions to the faculty were made between 1967 and 1972, and most of them (with a few notable exceptions) tended to be more theologically in tune with “the faculty majority” at St. Louis than with the general, confessionally-oriented and “conservative” faculty that had been at Springfield before that date.

The Springfield faculty did not comment a lot about the St. Louis faculty in their classroom instruction. This was generally true among both those who were sympathetic to the views of the St. Louis faculty majority and those who were not. Dr. Surburg, Dr. Buls, Dr. Scaer and Dr. Maier would occasionally speak to the current controverted issues, but they stuck to the theological issues and not to personalities. All of the faculty handled themselves with good professionalism.

The student bodies of the two seminaries got together on a couple of occasions for something new under the Tietjen and Schultz administrations. They had the opportunity to gather together for a “Day of Theological Reflection” to consider together issues that would affect LCMS parishes. The one held in 1972 was in St. Louis. Two prominent parish pastors, Dr. Paul Bretscher and Dr. H. Armin Moellering, made presentations regarding the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness. Dr. Bretscher was supposed to utilize the historical-critical method to examine the text and Dr. Moellering was supposed to use the traditional method of study. There was friendly sharing that took place between the St. Louis seminarians and the men from Springfield that were already acquainted with each other from days together at one of the Concordias. It was not especially enjoyable or helpful for the Springfield men who gave up a day but had no previous background with any the St. Louis students.

On another occasion, several of us who went to Springfield from the Senior College had our main class canceled for the day because one of our professors had to attend some kind of special meeting. We decided to drive the hundred miles down to St. Louis as a group to visit with our old college buddies and sit in on some of the controversial classes we had heard about and read about in articles from Missouri in Perspective, Christian News, and Affirm.

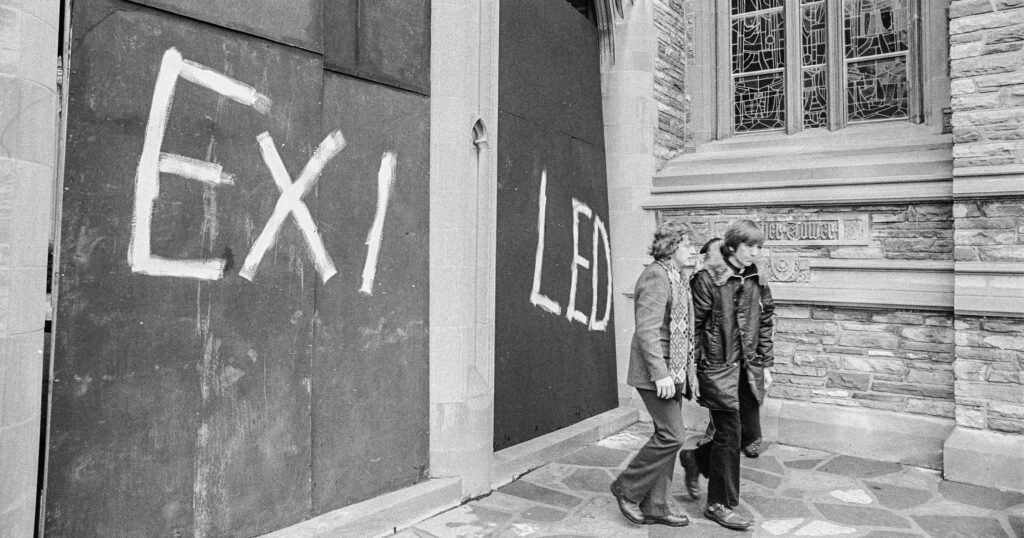

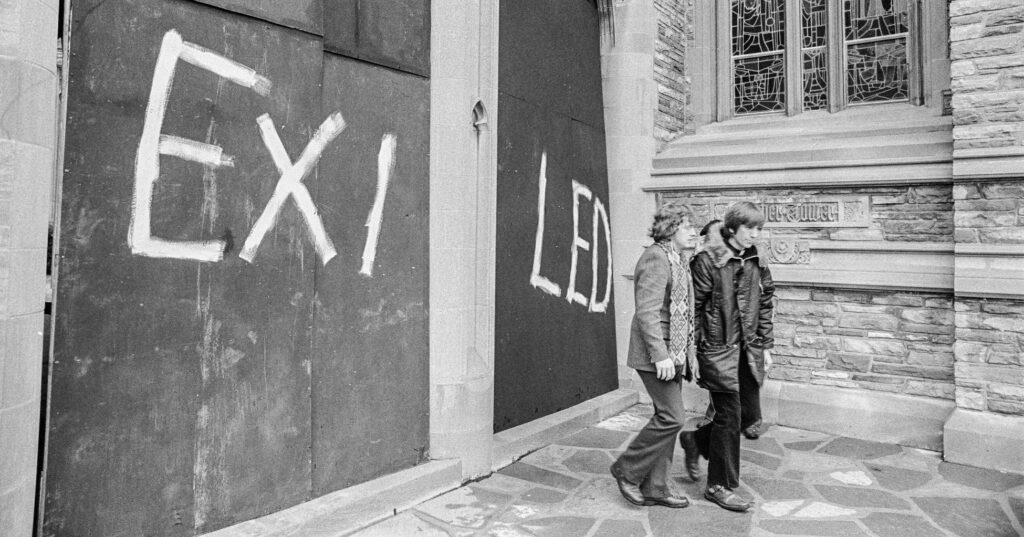

To our surprise, it was the day that John Tietjen was suspended by the Board of Control for the St. Louis seminary. No classes were being taught there that day, but instead the students met in the auditorium where the seminary normally had its chapel services. The student body president of St. Louis presided over a program informing the students and proposing a response by them. The “majority faculty” (i.e., all those who would shortly thereafter walk out and lead students in the formation of a “seminary in exile”) met together as a group off campus. The day had a number of organized activities, including the viewing of a video featuring Dr. Martin Marty of the University of Chicago Divinity School. He exhorted the students to stand with the faculty majority and demand that the board specify exactly which professors taught false doctrine and specify what that false doctrine was. It was the beginning of the moratorium on classes at St. Louis. Most, if not all, of the Springfield students who had made the trip found themselves praising the Lord that they had felt led to go to Springfield instead of St. Louis.

Things in the Synod began to heat up. President Schultz succumbed to pressure to leave the Springfield presidency and take a call to a mission congregation somewhere near the East coast. Dr. Henry Eggold was named the interim president of Springfield and Martin Scharlemann was named the interim president of the St. Louis seminary (filling the role that had been vacated by Tietjen’s suspension). Soon enough the academic year was winding down and it came time for the Council of Presidents to meet to place seminary graduates in their first assignments and to place vicars. Some district presidents wanted to place the Seminex students, and others insisted that it was no time for business as usual. They needed extra time to negotiate, and the Springfield students were “held hostage.” Dr. Eggold, John Costello, and Walter A. Maier II (who had been elected a Synod vice-president) insisted that the Council of Presidents stay to accomplish the task of their meeting before heading home. The vicarage assignments and candidate placements were delayed, but not past the end of the school year. It was a great inconvenience for many of the fourth year seminary students whose family and friends had made travel arrangements to be present for the Call service at Springfield, which had to be canceled and then subjected to last-minute attempts to be rescheduled. Sadly, there were those who went to Seminex who were lost to any kind of service in the Christian church.

The greatest impact on the Springfield faculty and students was the decision of the summer 1975 Anaheim convention of the LCMS to close the Senior College and relocate the Springfield seminary to Fort Wayne, Ind. The move took place in 1976 and was especially challenging for many of the faculty, a few of whom retired and did not make the move. The decision was obviously quite devastating to many of the Senior College faculty, all of whom lost their jobs and suddenly needed to make major changes in their lives and vocation. Most of the Springfield faculty that had been more sympathetic to the approach of those who formed Seminex found other employment and did not make the move to Fort Wayne.

The members of the seminary community that were at Fort Wayne for that first academic year in 1976–77 were subjected to a rather hostile environment. The Senior College phased out that year and shared the campus with the new arrivals that had been imported from Springfield. It was understandably very difficult for the Senior College faculty and staff to avoid having bitter resentment towards the seminary people, even though that group of seminary faculty, staff and students were not responsible for the situation. The situation lent itself to more hardening of polarized positions than would have been ideal.

In the end, both LCMS seminaries became better for the Missouri Synod in its mission and ministry after the 1974 crisis in Synod was resolved. The pains that were suffered by so many should not be minimized or overlooked, but ironically, it seems that now, after the strife of 50 years ago, the two seminaries have ultimately achieved a greater sense of mutual respect and comradery between them than existed in previous days.