Editor’s Note: This new series from LCMS Church Worker Wellness is hosted here on The Lutheran Witness site. Visit the “Ministry Features” page for regular Worker Wellness content.

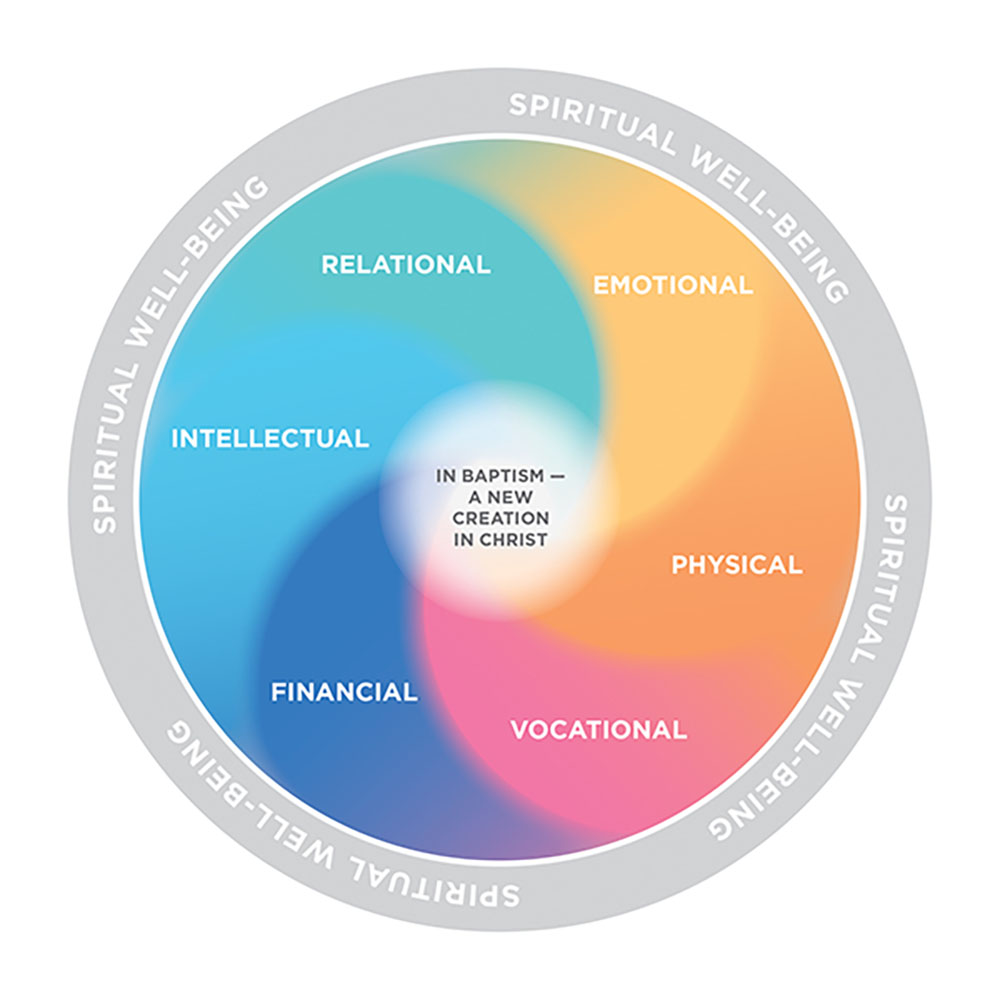

As Lutherans, we understand that the various aspects of our wellness — intellectual, emotional, relational, physical, financial and vocational — relate to and depend upon one another, and are all rooted in our Baptism, our true identity as new creations in Christ. We understand spiritual well-being not as a facet of our wellness, but as fundamental to any and all facets of wellness for a Christian.

The following reflection, written by the Rev. Dr. James Baneck, explores the theology of intellectual well-being.

This theological reflection first appeared in the 2021 booklet “A Lutheran Perspective on Well-Being” (LCMS).

Introduction

The Early Church theologian, Tertullian,[1] is attributed with saying, “Christians are made, not born.” Tertullian is describing the person born into sin and death and made to be a Christian through the water and the Word of Holy Baptism.

The same can be said for one in a church work vocation. Pastors, teachers, DCEs, deaconesses, church musicians and the like — they are not born, they are made. More precisely, church workers are made and formed by the church. Church work formation involves spiritual,[2] character,[3] confessional,[4] physical, emotional,[5] and even Synodical development.[6] This is a process that takes place over months and years.

One vital area of church worker development is intellectual well-being. Intellectual well-being involves, but is not limited to, a quality education; a desire and energy to learn; immersion in literature, philosophy, mathematics, composition, music, art and science; continued growth in thinking, reasoning and speaking skills; and growth in wisdom through practical experience, age, mentorship and continuing education.

The Purpose of the Educational Well-Being of Church Workers

We live in a time when people believe knowledge is obtained by opening an internet search engine, or asking our technological devices their opinions. We live in a world that likes when people appear “in the know.” Some believe they are already knowledge-able in all things.

Why is the educational well-being of church workers so important?

Integrity of the Call

First, there is the integrity of the call and the sacred vocation of serving God and neighbor in the church. The pastor’s call is the high and holy call from God and requires Him to be competent in this office.

For centuries, the church has called or appointed workers to support the Office of the Holy Ministry. The Lutheran church refers to these offices as Ministers of Religion—Commissioned. These include professors, teachers, directors of Christian education, directors of Christian outreach, directors of family life ministry, directors of parish music, deaconesses and parish assistants.

Whether ordained or commissioned ministers of religion, it is necessary and required of those serving in these offices to be intellectually competent and to maintain intellectual well-being for the sake of the integrity of their call/vocation.

Qualifications for the Call/Vocation

Those called to the pastoral ministry and in the auxiliary offices of the church undergo a comprehensive formation. Included in this formation is intellectual development.

When a man is properly called into the Office of the Holy Ministry, one of the biblical and confessional mandates is the examination of the candidate. “The Scriptures mandate that the candidate for the holy ministry be personally and theologically qualified for the office (1 Tim. 3:1–7; 2 Tim. 2:24–26; Titus 1:5–9; 1 Peter 5:1–4)” (2016 Res. 6-02).

A commissioned worker also undergoes thorough examination to be qualified for the office he/she serves. [7]The culmination of fulfilling these qualifications is in the installation vows of a Lutheran school teacher: “Will you, trusting in God’s care, seek to grow in love for those you serve, strive for excellence in your skills, and adorn the Gospel of Jesus Christ with a godly life?”

Just as the surgeon’s work appears to only be operating on the body, fixing the parts, sewing the patient up and checking on them in post-op, a church worker’s vocational work is not only that which is visible. However, consider the invisible intellectual knowledge base required of both vocations.

Consider the pastor who gives pastoral care to the drug addict, the dying young father, the woman wrestling with sexual orientation, the pregnant teenager, the soldier with PTSD and other everyday pastoral situations. Consider the knowledge of the Lutheran school teacher who teaches multiple subjects, students living in dysfunctional families, the slow learner, the accelerated learner, the unruly learner and more. The intellectual well-being and skill set of every man and woman in church work vocations is necessary, astounding and intentional.

Church workers do not just learn skills. Their task is not performing mere functions. Preaching is more than public speaking. Teaching is more than instilling knowledge. Organ playing is more than touching keys. Directing youth is more than planning a youth meeting.

Apt to Teach

St. Paul writes to Timothy, “Preach the Word; be ready in season and out of season; reprove, rebuke, and exhort, with complete patience and teaching. For the time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own passions, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander off into myths” (2 Tim. 4:2–4).

These words are specifically written to the pastor. However, they have appropriate application to all workers in the church. This is why The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod forms her workers through a thorough liberal arts education, providing them a broad educational experience.

For a pastor to fulfill his call, he must be intellectually equipped. He must have a knowledge of sin, grace, Jesus Christ, man, the philosophies and myths of this world, human will, skills in articulation and speech, as well as a knowledge of himself, a knowledge of his hearer, and a knowledge of God and the whole council of the Word. How does he relate to his hearer who is a physician, someone emotionally challenged, a young child, a truck driver, a war vet, a stay-at-home mom, an engineer, a person of a different ethnicity than him, and so on? What does he know about how his hearer learns and communicates (visually, verbally, through stories, through lecture, intellectually, emotionally, one on one, in groups, etc.)? To be apt to teach, the teacher must learn, and continue to learn — not only subjects and theology, but people and how to relate to people.

Robust Intellectual Education

Deplorable Conditions and High Standards

In his preface to his Small Catechism, Luther writes, “The deplorable, miserable conditions which I recently observed when visiting the parishes have constrained and pressed me to put this catechism of Christian doctrine into this brief, plain, and simple form. How pitiable, so help me God, were the things I saw: the common man, especially in the villages, knows practi-cally nothing of Christian doctrine, and many of the pastors are almost entirely incompetent and unable to teach … So look to it, you pastors and preachers. Our ministry … has become a serious and saving responsibility.”

Historically, the church has learned the importance of the intellectual well-being of their pastors, teachers and workers through painful mistakes of placing unqualified workers in the field with no continuing intellectual support, including in Luther’s own Saxony, and the Lutheran Church of the Stalinist (WWII) era.[8]

While The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod sets high standards for ordained ministers, no less is demanded from her commissioned minsters. There is no debate that our American culture is also in “deplorable conditions,” especially concerning marriage, sexual identity, religious liberty and life issues. For this reason, the church calls for a robust educational formation toward the intellectual well-being of her workers, both ordained and commissioned.

The LCMS strives to provide intellectual well-being to all her workers not for the sake of having smart people. This excellence is about serving God’s people in their faith and life here on earth with the view of life eternal. First and foremost, learning the Holy Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions is for the sake of teaching it to God’s people, whereby the Holy Spirit creates and sustains eternal saving faith.

The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod believes her workers are handling the holy things (Word and Sacraments) of God for the eternal faith and life of God’s people. To this end, she sets high educational standards in forming men and women for her various vocations.

Rast writes:

Admission to Wittenberg [in Luther’s day] assumed familiarity with the Latin language and the classics. The gymnasium process of education was assumed. The responsibility of the university was to help the students become fruitful users of these tools for the sake of the proclamation of the Gospel. As the university itself states: … “How can [the student] expect to be able to interpret sacred dogma without the mastery of the correct use of Biblical exegesis, or in case he fails to grasp the context of passages form which conclusions are drawn?”[9]

Continuing Education for the Intellectual Well-Being of Workers

Continuing education is encouraged and expected for the intellectual well-being of our workers. In his Instructions for the Visitors of Parish Pastors, Martin Luther writes, “For it was in this kind of activity [visitation] that the bishops and archbishops had their origin — each one was obligated to a greater or lesser extent to visit and examine. For, actually, bishop means supervisor or visitor, and archbishop a supervisor or visitor of bishops, to see to it that each parish pastor visits and watches over and supervises his people in regard to teaching and life” (AE 40:270).

Not only pastors, but all church workers are evangelically supervised with the encouragement of continuing education to grow and excel in their vocation. This is an expectation, and sometimes requirement, of the worker.

For the sake of intellectual growth and well-being, the church provides many opportunities to her workers for continuing education. Resources like Post-Seminary Applied Learning and Support (PALS) and Preach the Word are Synod-administered opportunities for pastors. Churches and Lutheran schools also supply their workers with many opportunities, choices and resources for intellectual well-being in their field. The church also encourages continuing education through self-reporting in their church-worker files. Other opportunities are provided by other Synod and district conferences and resources. Intellectual well-being is a lifelong process of tending to the Word, our vocation and personal growth, rooted and grounded in the gifts of God to His people on earth.

[1] 160–220 A.D.

[2] Spiritual development encompasses a thorough knowledge of Holy Scripture, a father confessor/pastor, a godly family, immersion in the liturgical life of the church, reception of the Lord’s Supper and daily prayer.

[3] Character development encompasses a baptismal faith and life. This baptismal, sanctified life includes repentance, the fruits of the Spirit, integrity, virtue, manhood, manners and civility.

[4] Confessional development encompasses a thorough knowledge of Holy Scripture, a father-confessor/pastor, a godly family, immersion in the liturgical life of the church, reception of the Lord’s Supper and daily prayer.

[5] Physical and emotional development encompass the categories brought out in the First Article of the Apostles’ Creed, including healthy choices and living, exercise, healthy diet, an understanding of self, interpersonal relationships, and the capacity to navigate physical and emotional issues.

[6] Synodical development encompasses a thorough understanding of the Synod’s structure, the LCMS Handbook, ecclesiastical supervision, the call process, Synod and district conventions, convention resolutions and church worker conferences.

[7] Lutheran Service Book: Agenda (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2006), 212.

[8] Lawrence R. Rast Jr., “Pastoral Formation in the 21st Century: The Pedagogical Implications of Globalization,” Concordia Theological Quarterly 83, no. 1 (2019): 137–156.

[9] Rast, 142.

In the coming months, you will hear more about the work of LCMS Church Worker Wellness initiative, including new resources and more. Stay tuned to Reporter, The Lutheran Witness and the LCMS Church Worker Wellness site for updates.

A disciple, by definition, is a learner. Any learning that is worthwhile genuinely benefits oneself and others.

As we are blessed in the Lord, we can learn to be fruitful (John 15:5) —

to God’s everlasting glory (John 15:8).

As we learn to be fruitful, we are further blessed in the Lord (John 13:17) —

to our everlasting joy (John 15:11).

“His divine power has granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness…. For this very reason, make every effort to supplement your faith with virtue, and virtue with knowledge…. For if these qualities are yours and are increasing, they keep you from being ineffective or unfruitful…” (2 Peter 1:3-8 ESV).