A literary reflection by Davis Smith on Herman Melville's novel "Moby Dick." This is one installment of a monthly series providing reflections on works of literature from a Lutheran perspective.

“Call me Ishmael.” Herman Melville’s Moby Dick is practically synonymous with intimidating reading, but its famous first sentence is as basic as possible. At the mention of Moby Dick, most people think of a huge, difficult “classic” that they may have been forced to read in high school, known to be interminably dry and boring. Most people know the essential concept of the work — quite simply, Moby Dick is about a whale. This is even reflected in Melville’s complete title: Moby Dick; Or, the Whale. It tells the story of how the doomed crew of the Pequod, helmed by the mad Captain Ahab, goes after the mighty White Whale in a frenzied hunt. Sounds pretty straightforward, right? Still, many who have not read it fear its length and daunting reputation; and many who have read it despise it for its incredibly elaborate prose and seemingly endless stacks of pages that go on and on about a subject matter for which most people care little.

Nonetheless, Christians should consider facing the difficulties of this ubiquitous yet seldom-read text to enter its strange, solemn, unforgettable world. Even though the novel’s treatment of religious themes is dark, skeptical, and only points to the Gospel through its absence in the work, Melville’s exhaustive examination of the whale encourages the reader to contemplate and interpret nature as a glorious testimony to the unfathomable majesty of its Creator.

One reason for embarking upon the voyage of the Pequodalong with Ishmael, Ahab and the other men in Melville’s motley cast of crew members is simple: to enjoy the work of a master. In its magnificent breadth and ambition, Moby Dick is one of the richest texts in world literature. Melville began his career in the 1840s as a popular writer of exciting, sensational adventure novels. But as his style became more serious and refined, the American public turned on him. When it was published in 1851, Moby Dick was considered a spectacular failure. The vivid descriptions of sailing life and the whaling industry are drawn from the storehouse of his own experiences working on whaling ships as a young man. But for this novel, Melville wrote in a dense, magisterial, even extravagant style modeled after that of Shakespeare and the King James Bible. His command of the English language is of an unparalleled beauty and mastery, and his prose engages all of the senses to immerse the reader in the strange, perilous, spectacular world of life on the high seas. In the words of Ishmael, it opens up the “great flood-gates of the wonder-world.” A first-time reader of the novel would do well to attend to the various genres, tones, and colors — drama, sermon, soliloquy, science, philosophy and narrative — which comprise the many chapters of this encyclopedic novel, and to consider how they all team up to form an unmatched American epic that spans quite literally the entire globe. The Christian reader also has a unique advantage in approaching the novel, since he or she can recognize the vast array of biblical allusions which Melville weaves into his work.

Even before “Call me Ishmael,” Melville outlines his entire work in a long list of prefatory quotes (“Extracts”). These quotes contain every mention of whales which Melville could find in world history, beginning with Genesis 1:21 (KJV: “And God created great whales”), and ending with the colloquial sailors’ songs of his day. These extracts provide a helpful “road map” for the reader. Melville’s main goal is to consider man’s relationship to nature through the dominating focal point of the whale, which he fascinatingly equates with the biblical Leviathan. In fact, the Book of Job, with its intensely emotive poetry, anguished reflections on suffering and the goodness of God, and overwhelming descriptions of natural wonders in God’s response to Job, is perhaps the most immediate influence of Moby Dick. Job 41:1–4 offers these rhetorical question from God: “Can you draw out Leviathan with a fishhook or press down his tongue with a cord? Can you put a rope in his nose or pierce his jaw with a hook? Will he make many pleas to you? Will he speak to you soft words? Will he make a covenant with you to take him for your servant forever?” In an American economy that hunted and harvested these mighty beasts for their oil, these lines took on an especially haunting resonance.

To read Moby Dick against this backdrop is to experience a great revelation about its meaning. Like Job, Ishmael continually examines the world and struggles to make sense of it. He rightly sees nature as a massive book of God’s revelation about Himself: a text to be read and interpreted with close attention, awe and submission. Like turning a diamond under a lamp to reveal all its intricate facets, Melville approaches the subject of the whale from every imaginable angle — scientific, poetic, mythological, whimsical, philosophical — to reveal the majesty, terror and grandeur of this crown jewel of God’s handiwork. Psalm 19, which famously begins with “the heavens declare the glory of God,” provides another rich Biblical background text. The psalmist begins by marveling at the inexpressible beauty of creation, and concludes by delighting in the Law of the Lord. Most of us have had an experience with nature like this — an encounter with mountains, seas, waterfalls or wild animals that encourages us to join in with another hymn of the psalmist: “When I look at Your heavens, the work of Your fingers, the moon and the stars, which You have set in place, what is man that You are mindful of him, and the son of man that You care for him?” (Psalm 8:3–4).

The “creation” psalms, God’s rebuke of Job, and Ishmael’s narrative in Moby Dick all reorient our sight from rash self-centeredness and toward our apparent pitiful insignificance within the “book of nature.” Melville, though not an orthodox Christian, illustrates an attitude of piety and humility toward mystery through the attempts of Ishmael to read the text of nature. He also portrays the opposite of this attitude in the fascinating, tragic figure of Captain Ahab, who is similar to Milton’s Satan and Victor Frankenstein: a man concerned only with his own powers of domination, and willing to drive the entire crew to their death in his futile attempt to gain revenge on the whale who injured him.

But as much as reverent meditation on nature can give us perspective, Scripture and the Lutheran Confessions are clear that this is woefully inadequate for a complete grasp of reality. The theological truths in Moby Dick all belong to the realm of the Law, which curbs, convicts and guides the sinner toward what he ought to do but is incapable of providing the comfort and assurance of salvation. Apart from the Gospel, the insignificance of man in creation is cause for angst and despair. This is why Melville can offer no consolation in his work beyond a resigned acceptance of nature’s superiority and the injunction for man to marvel at rather than attempting to master the Leviathan. There are no hints toward the great statement of hope at the center of Job’s laments: “For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another. My heart faints within me!” (Job 19:25–27). Rather, Melville’s God is sovereignly impersonal and distant from our concerns.

Readers of this great American epic will experience high artistry, characters and ideas of a biblical scope, and many memorable encounters with the Law as discerned through general revelation and the examining of the heart. It is a towering masterpiece and an unforgettable voyage. But it is nonetheless a highly modern work. It grapples with the purpose of humanity in the presence of a God who leaves ample testimony of His existence but seems to care nothing for us. Only the Christian can truly love the beauty of creation and the Law, seeing them through the lens of the self-emptying Incarnate God who enters His creation to make His children partakers of His glory. Enjoy the baffling complexities and ecstatic delights of the novel, praise the Holy Trinity for the marvels of nature, and give thanks to Him that He has satisfied Melville’s tortured longing for meaning through the healing balm of the Gospel.

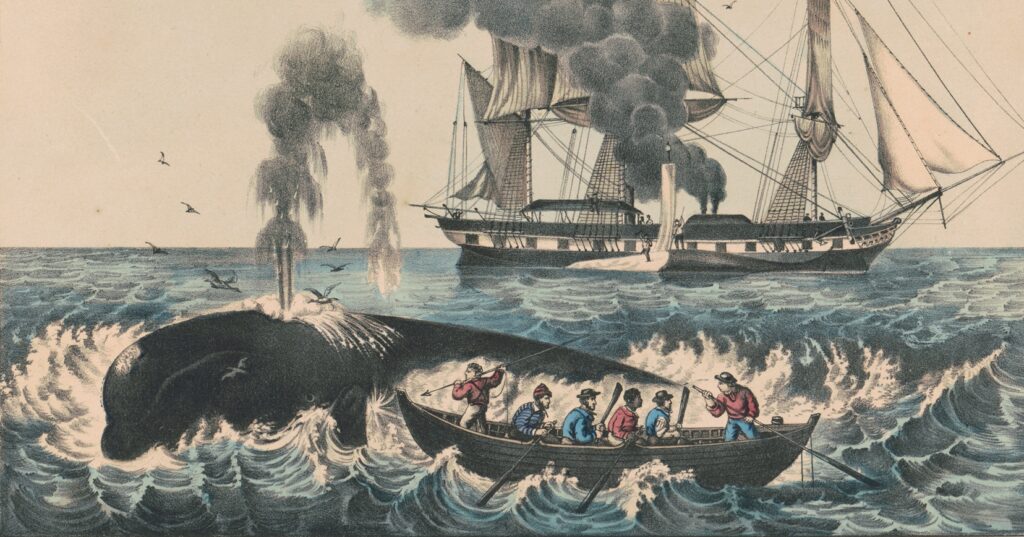

Cover image: “Whale fishery; attacking a right whale,” by Currier & Ives, 1835–1907.