An art reflection by Kelly Schumacher (Uffenbeck) of Agnus Dei Liturgical Arts on the illustrations of Trina Schart Hyman. This is one installment of a monthly series providing reflections on works of art and music from a Lutheran perspective.

As I look back at my childhood, I can see the many ways that illustrations formed my imagination. As a child, my parents gifted me every year with Caldecott children’s books — with beautiful realistic illustrations. One of my all-time favorite books growing up was Saint George and the Dragon, illustrated by Trina Schart Hyman and retold by Margaret Hodges.

Today’s information-technological world is so fast paced, and I am trying to raise my daughter to not get sucked into the digital abyss, but instead get lost in the world of books. As I do so, I have had many opportunities to reflect on the nature of modern illustration.

Teaching the faith through illustration

In the art world, illustration has fallen to second-tier status over the past century. According to contemporary definitions, “fine art” is an expression of self and can be abstract or conceptual. The expression open to interpretation by the viewer.

For this reason, illustration receives disdain in the fine art world today. In illustration, the artist reads the text and does his or her best to take the words and literally flesh them out. The personal voice of the artist comes through, but the intent of the art is to support the text and be faithful to the text. The illustrator serves the reader by helping him understand what is happening in the story.

In years gone by, fine art and illustration were one and the same. If you visit an art museum, many of the paintings illustrate stories from the Bible or myths. Some paintings show interiors, still life objects or scenes from everyday life. But things have changed in the art world. And we see the results of modernity and post-modernity not just in museums, but trickling down right into the illustrations of many children’s books and other children’s material.

Many modern illustrations of Scripture and Bible stories are too conceptual and abstract in nature. This matters. For children (as for all of us), illustration is not just auxiliary to the benefit of reading and being read stories: it is essential to it. The quality and nature of children’s book illustrations can be as important to the formation of a child as the story told in the book’s pages.

We can see this same shift reflected in the designs of many modern churches and the designs of stained glass windows. Instead of historical events, we see flashes of color, abstract designs and shapes. In many cases, such designs are explained to be representations of the Holy Spirit. And yet, the Holy Spirit is not abstract and does not reveal abstract realities but concrete realities. The Holy Spirit reveals to us the God-man, Christ, who came to be a baby and bleed and die for the sins of the world on a wooden cross. If we could time travel with a camera, we could take a picture or film each of these events happening in sequential order. We receive this Christ in, with and under bread and wine in the receiving of the Sacrament for the forgiveness of sins. This goes beyond our feelings and into the world of spiritual realities that are not vague and amorphous but concrete and sure.

Similar mindsets have also come to influence modern theology. The LCMS is fighting an uphill battle as we continue seeking to look at Scripture through the lens of Christ and the Lutheran Confessions, instead of personal feelings being our hermeneutic.

I would propose, dear reader, that one of the ways to help us and our children read Scripture faithfully is through faithful, realistic art and illustration. If we are wondering how to teach the faith to our children and to our neighbor through art, I believe that classical and realistic illustration is the answer. My personal feelings about Jesus are not the answer, my interpretation of the Bible is not the answer, my experience of how I feel Jesus in my heart is not the answer. All of these things are fleeting and will falter. The wonderful news is that we can look at Scripture and read about One who will never fail or falter. We can read about who Jesus was and who He is and that He is coming again.

Saint George and the Dragon

Now, getting back to Trina Schart Hyman, one of my favorite illustrators of all time, and Saint George and the Dragon.

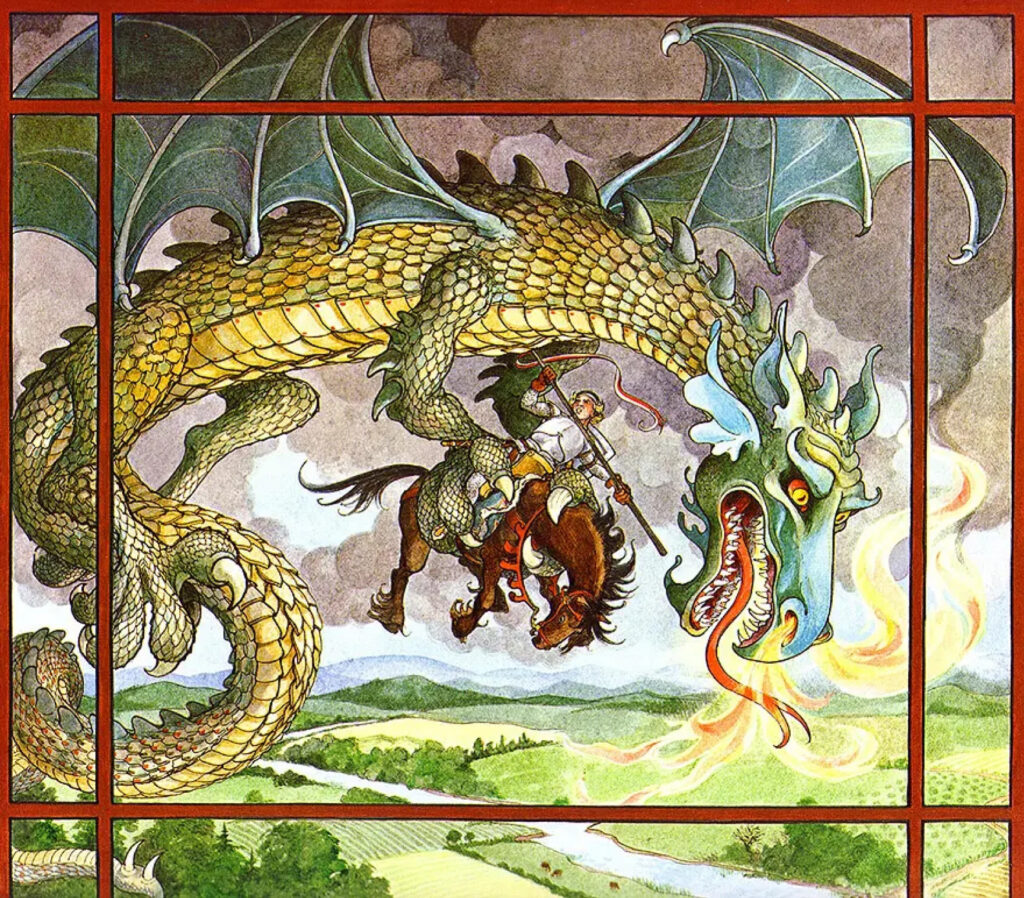

Saint George serves as an archetype for Saint Michael and Jesus Christ, who slay the dragon in the book of Revelation. Though there is much Christian symbolism in the book, I want to focus instead on the artwork of Trina Schart Hyman. Hyman’s composition, story boarding, and use of line and of artistic materials help tell the story.

I have always loved how the font on the cover of Saint George shows the letters “S”, “G”, and “D” as dragons. What a creative touch. The borders contain patterns and florals that the illustrator has drawn from medieval Christian art. There are layers of borders with hints as to what will happen in the story. This method of illustration provides clues to the reader as to what will happen next, without giving the full story away. Hyman is asking us to pay attention as the story unfolds.

Hyman worked on illustration board using watercolors and sometimes oils over gesso. She worked in layers, letting the light of the illustration board shine through — almost the same technique as a stained glass artist uses. She used fine black lines to outline and unify the medieval world she depicts. I am reminded of illuminated manuscripts where monks painted pictures to illustrate the Bible and used fancy calligraphy to adorn the Word of God. Hyman uses the same passion and care in her illustrations.

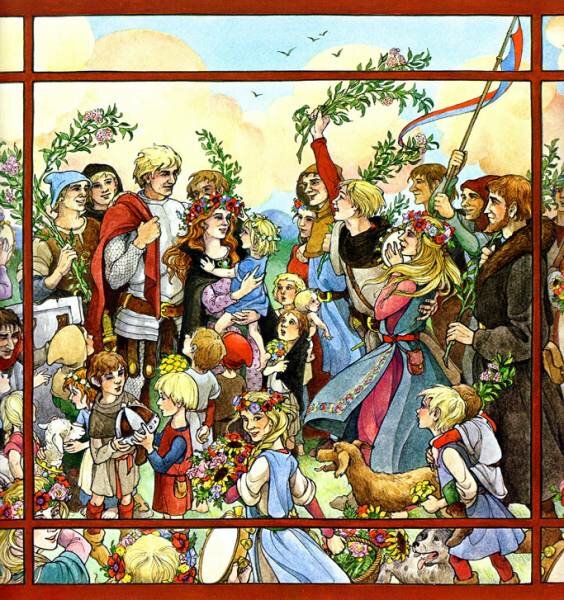

When Hyman depicts the dragon with all his scales and fury, she pays attention to the details of the character and makes the backgrounds more subtle in atmospheric perspective, to create depth and focus. The characters are always clear, since they tell the story. Another favorite page in this book is when the reptilian beast is slain and the peoples of the land are rejoicing with flowers, musical instruments and loud singing. The children are adorned with crowns and full of excitement to see the great victor Saint George and his beloved Una. This rejoicing reminds me so much of Palm Sunday, Easter Sunday, and the rejoicing we will partake in singing around the Lamb of God at the Resurrection of all flesh at the return of Christ Jesus.

This carefulness and intentionality is what I would like to see a new generation of Lutheran artists strive for. Rather than imitating the forms and styles of this world, we would do well to look to Christian art history, imitating forms and styles from within the tradition of our faith. If Lutheran artists seek inspiration from artists such as Hyman, it will serve us well as we work to preserve our Lutheran heritage for generations, providing more seeds of faith that will blossom into abundant good fruit.

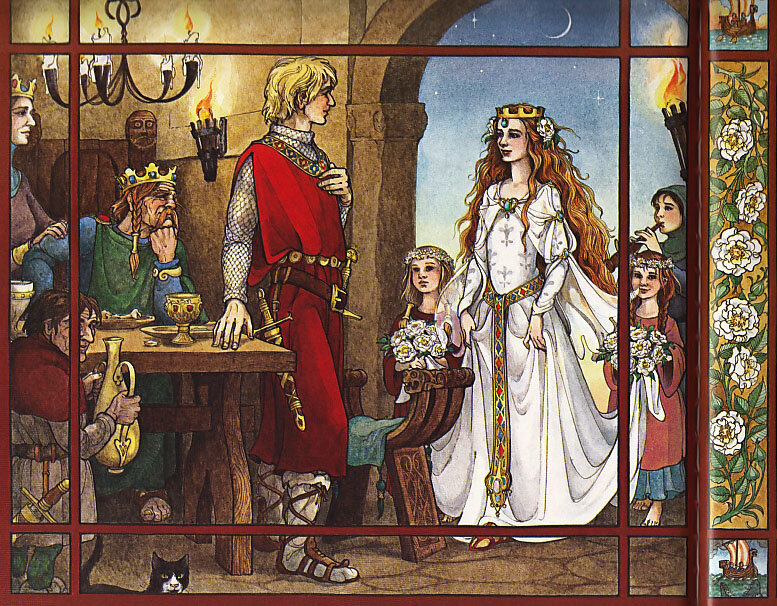

Another great illustration of Hyman’s in the book is wedding of Saint George and Una. The text says, “Whenever he looked at the brightness of her sunshiny face, his heart melted with pleasure.” Though these words are in the context of a wedding, I think it is a perfect recipe for creating religious art in a dying world. Can we make art that melts hearts of stone with pleasure into hearts of flesh? I think we can. Can we be the fragrance of Christ in a world that reeks with the stench of death? Again, yes!

The more we cease to conform to the patterns of this world, and instead seek to be consistent with Scripture and God’s design in creation (His fingerprints are all over it), the more we can magnify His Holy name through our art and our lives. We may not be accepted in this world for what we believe and confess — but this is nothing, if we have proclaimed our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in all His truth and in all His beauty.

Cover image: “Story of Golden Locks,” Seymour Joseph Guy, 1870. The MET Collection.

Is the message in art subliminal to those who don’t take time to understand it?

Does LCMS need to educate members about art and if so how? Classes for youth in LCMS schools? Sunday school and adult bible class?

Hi Steve! I wrote the article – I do speaking engagements for all of these things if you would like to schedule them. I make art too – my website is agnusdeiarts.com. I am working on helping educate Lutherans (and beyond) one step at a time.