A literary reflection by Kevin Martin on Evelyn Waugh's "Brideshead Revisited." This is one installment of a monthly series providing reflections on works of literature from a Lutheran perspective.

Mr. Evelyn Waugh’s classic novel (he was a guy, though his first wife was also named Evelyn: he called her “Shevelyn,” which may have factored into their break-up) Brideshead Revisited paints a picture of the church as a hopeful community for those who have lost hope in everything else.

We meet Charles Ryder, in the opening pages of Brideshead, in an army camp in WWII Britain circa 1943. He’s fallen out of love with the army. He commands C Company, which has been training for months with no action or end to the war in sight. The army promised the kind of community Ryder was missing in his life. A just cause. A fearsome enemy. The defense of the British homeland and way of life. But the mindless army bureaucracy and the senseless exercises have alienated Ryder from his martial community.

C Company has arrived, in middle of the night, at a new camp, a magnificent English country house called “Brideshead.” Hooper, Ryder’s comically inept second-in-command, exclaims: “Ryder! You’ve never seen anything like this house—it even has a Catholic chapel!” Ryder cuts Hooper off: “Yes, I have seen it before, Hooper. It belongs to friends of mine.”

The book is a long reminiscence, beginning with Ryder’s Oxford school days. After throwing up in Charles Ryder’s ground-floor Oxford rooms (after a night of heavy drinking), Lord Sebastian Flyte invites Charles to luncheon (along with Aloysius, Sebastian’s childhood teddy-bear, which he treats as comically sentient) to apologize. They become fast friends. One lovely summer day, during Oxford’s famed Regatta week, Sebastian takes Charles to Brideshead Castle, and so begins a long affair with the house and the Flyte family for Charles.

Charles Ryder’s biological family has provided him little community. His mother died in WWI. His father was aloof and casually cruel. His cousin Jasper hectors him with conventional but lousy advice.

Oxford, initially, thoroughly enchanted Charles. It promised an enduring community, a place to belong. But Sebastian Flyte and his family captivates, more. The Flytes (and they are flighty!) make Oxford dull, by comparison. Sebastian is expelled for not doing any work. Charles drops out after his second year and goes to Paris to become an artist — becoming a successful architectural painter of English country houses (like Brideshead) to great acclaim and affluence.

But art (and money) also fails to provide a meaningful community for Charles. As does his lovely wife Cecilia, who is unfaithful to Charles. Eventually, Charles falls in love with Sebastian’s sister Julia. This leads to Charles and Julia divorcing their spouses in order to marry each other.

Lady Marchmain, Sebastian and Julia’s mother, has lived apart from their father, Lord Marchmain, since he ran off with an Italian dancer after WWI to Venice. After Lady Marchmain’s death, Lord Marchmain returns to Brideshead to spend his final months. He has decided to leave Brideshead Castle to Charles and Julia. Their illicit affair warms his cold heart.

Lord Marchmain has lapsed from the Catholic church for over two decades. But, as he lies dying, a priest visits. And in his last moments, Lord Marchmain receives absolution and laboriously makes the sign of the cross, reconciling with Christ’s church.

Charles and Julia meet in a hallway at Brideshead after her father has passed. She tells Charles she cannot marry him, though she loves him very much. Such a marriage is against the Catholic faith, and Julia realizes the church is the one community that truly matters, the one she cannot forsake. And so, Charles and Julia part, unhappy, each apparently condemned to a life of solitude.

Mr. Waugh (one of the greatest English prose stylists) deftly portrays how family, Oxford, art, vocation, the army, great wealth, wars, patriotism all fail to provide Charles and Julia the community they truly require. Because none of these provide a hopeful community. Indeed, all of them will fade away because of troubles, sins and finally, death.

But there is one community that is truly hopeful. One alone that alone promises eternal life: the Christian Church. Communion with Jesus Christ gives a hope, a purpose, a life that sin, death, and hell can never destroy. Finally, for Charles and Julia, it is that hope, that community, that alone truly matters.

Holy Scripture calls the church a “communion of saints.” Brideshead Revisited shows a cast of characters that do not seem at all saintly — at first glance. Charles figures his relationship with Sebastian involved sins of a grave nature. Charles himself is a terrible snob, rather aloof, sardonic, and condescending. He is quite indifferent to his family responsibilities. Charles abandons his wife and children. Sebastian becomes a hopeless alcoholic, self-exiled to North Africa. Julia has committed some pretty grave sins of her own.

But, Mr. Waugh’s genius is to show us all these characters are part of the communion of saints — the Body of Christ, who alone gives us hope because He, and He alone, does not desert us, gives us His forgiveness, mercy, and unconditional love. Communion with Christ Jesus alone gives hope, alone makes us whole.

There’s a moving scene on the last pages of Brideshead Revisited. After visiting Sebastian and Julia’s elderly nanny, Charles encounters Hooper. Hooper doesn’t understand how one family can need a house this size. He asks: “What’s the use of it?” Charles quips, “I suppose Brigade are finding it useful.” Hooper replies, “But that’s not what it was built for, is it?”

Charles says “no — but that’s one of the joys of building something. You never know how it will turn out.” And then he confesses, “I’m homeless, childless, middle-aged, loveless, Hooper.” Hooper thinks he’s joking. But Charles is quite serious, now.

Ryder goes to the chapel of Brideshead. Dips his finger in the baptismal font. Crosses himself. Prays in front of the tabernacle lamp. And then, he reflects:

Something quite remote from anything the builders [of Brideshead Castle] intended has come out of their work, and out of the fierce little human tragedy in which I played; something none of us thought about at the time: a small red flame—a beaten-copper lamp of deplorable design, relit before the beaten-copper doors of a tabernacle; the flame which the old knights saw from their tombs, which they saw put out; that flame burns again for other soldiers [like Charles Ryder], far from home, farther, in heart, than Acre or Jerusalem. It could not have been lit but for the builders and the tragedians, and there I found it this morning, burning anew among the old stones.

Ryder leaves the chapel and returns to the room where the officers are gathered. “You’re looking unusually cheerful to-day,” says Hooper.

In the church — though homeless, childless, middle-aged, and loveless — Charles Ryder has found a communion and a hope for the life of the world to come, which, in the darkest times, puts true cheer in our hearts and quickens our step, and will, unfailingly, guide us to our heavenly home.

Evelyn Waugh was a converted Roman Catholic. But the Lutheran Church provides this hope for the homeless, helpless, loveless, and forlorn much more powerfully than Rome. We know that we have the unconditional forgiveness of sins by faith alone, in Christ alone, by His grace alone — which makes us part of the communion of saints — the best, most hopeful community there is.

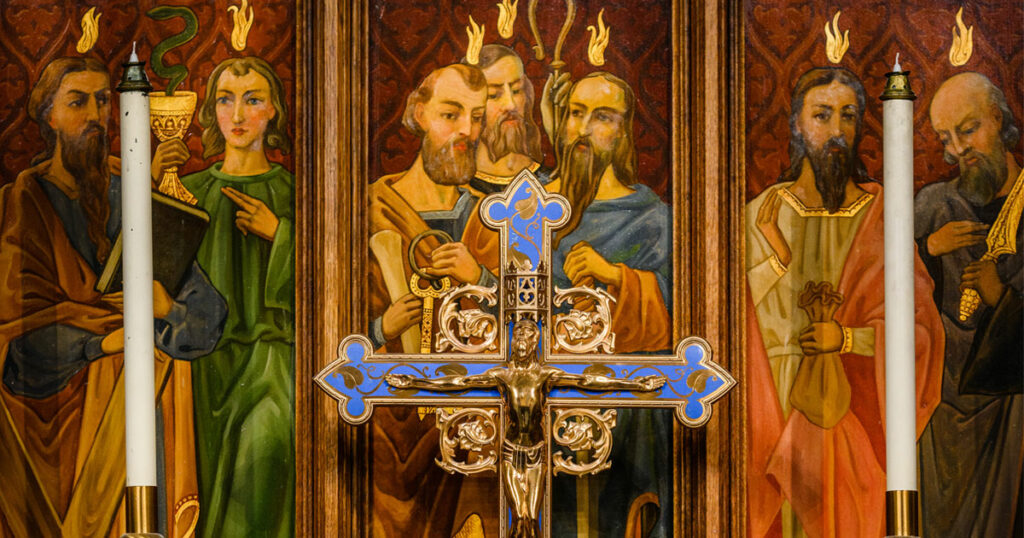

Cover image: “Schloss Milkel in Moonlight,” Carl Gustav Carus, 1833–35.

The dramatized version of this novel (with Jeremy Irons) has slways fascinated me. Yet I see his “salvation” as a future reacceptance of atheism and of his talents and loves as the things that really matter, not the conversion to Catholicism that brings so little joy or purpose to people like Sebastian and Julia. This story allows me to examine members of a faith I abandoned, much as an anthropologist studies people of far different cultures.