Editor’s Note: This new series from LCMS Church Worker Wellness is hosted here on The Lutheran Witness site. Visit the “Ministry Features” page for regular Worker Wellness content.

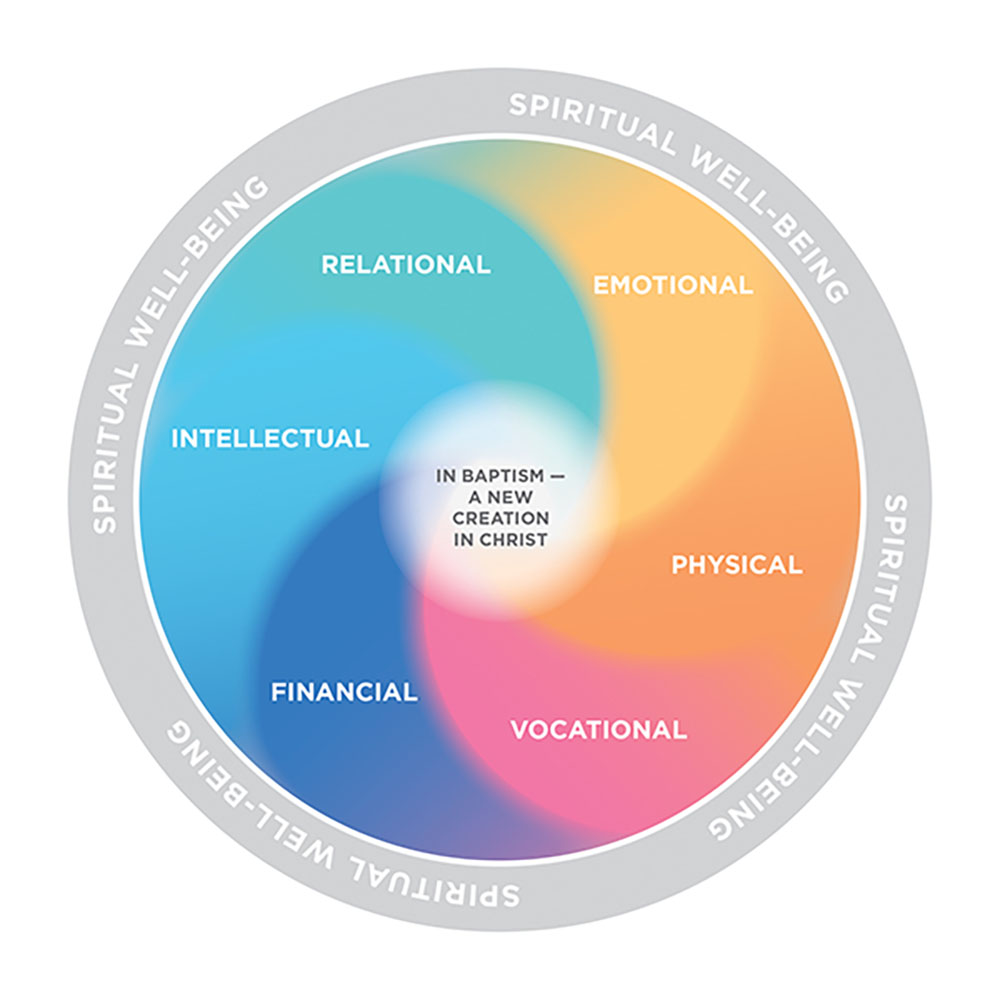

As Lutherans, we understand that the various aspects of our wellness — intellectual, emotional, relational, physical, financial and vocational — relate to and depend upon one another, and are all rooted in our Baptism, our true identity as new creations in Christ. We understand spiritual well-being not as a facet of our wellness, but as fundamental to any and all facets of wellness for a Christian.

The following reflection, written by the Rev. Dr. Robert Zagore, explores the theology of spiritual well-being.

As church workers, our greatest spiritual error can be believing that we know the Gospel and need to move on to something else for our comfort and sustenance.

The daily life of a church worker is often engaged with the Means of Grace and the church, without being nurtured by them. We read the Bible for professional purposes. We attend church services and worry about the experience everyone else is having. Church workers and their families are always watched and judged. Fellow Christians make us the object of callous or hurtful criticism. We try to endure the most difficult times with a kind smile, a joyful heart and a steady disposition. Because of this, we can come to envision the church, the classroom, the Bible and worship as places of obligation and even hardship. It is a recipe for spiritual starvation and burnout.

We often mistakenly assume that since we know the Gospel but are still pressed down, burdened, accused or guilty, that something more than the Gospel is needed. We try to change our behavior: accomplish more, pray more, study more. It does not work because it cannot work. Since hard work fails, we try to find comfort in worldly pleasures. One-third of church workers say they are bound up in destructive compulsive behaviors. Rather than comforting us, these bind us to our shame. Perhaps this contributes to the anxiety and depression with which a quarter of our church workers have been diagnosed.

In the 2019 worker wellness survey, one-third of church workers self-reported their work is getting in the way of their relationship with God. Our work, like all work done here on earth, is accomplished “by the sweat of [our] face” (Gen. 3:19). Unfortunately, when you “work for the Lord,” it is easy to think of hardship as His rebuke. Since the consequence of personal failure seems to have eternal impact, the guilt and shame of our troubles can be overwhelming. The church, the Word, the prayers become work-related burdens. Our hearts and logic plead to find comfort elsewhere. At the very time we should run for refuge in our Father’s grace, it becomes easy to run from it instead. This is an old problem.

Understanding the “why” of spiritual well-being

Back in 1518, during the Heidelberg Disputation, Martin Luther described the problem using the terms “theology of the cross” and “theology of glory.” During the dispute, Luther surprised everyone by declaring that even good and evil cannot be understood apart from God’s revelation. “A theologian of glory calls evil good and good evil. A theologian of the cross calls the thing what it actually is.”1

If we look at life apart from God’s Word and promises, we can easily find ourselves trying to escape our only refuge and strength. All fallen people are by nature theologians of glory. We believe that comfort, earthly peace, riches and temporal success are signs that God is with us. For a theologian of glory, suffering, hardship and rejection are signs that we are failing, or worse, that even God is rejecting us. Luther contradicts that. We need a theology that understands that the cross of Jesus Christ is the Lord’s way of saving the world. That theology of the cross continues with the martyrdom of the apostles, the suffering of Christian martyrs or even us. The church or church worker that runs from the cross may likewise run from their role in God’s ongoing saving work.

Theologians of glory can abide a little suffering. It adds glory to our story. A quick, glorious martyr’s death can be celebrated, even sought. What is harder to comprehend is the meaning of what Luther called anfechtungen, or “pokes of a spear,” the thousands of public and private wounds wrought by daily life. Good and evil people alike suffer from them in a dying world. We live in a dangerous place where bad things happen to everyone. But why does God permit this for His children?

As traumatizing as these can be, Luther warns against trying to explain the “why.” Neither our behavior nor our circumstance can reveal God’s plan for us. There are areas of life that will always be shrouded in mystery, and no effort on our part will explain the “why” of it all. “That person does not deserve to be called a theologian who looks upon the invisible things of God as though they were clearly perceptible in those things which have actually happened [Rom. 1:20].”2 We cannot interpret God’s hidden will. We cannot know what God does not reveal. Therefore, if we are to know His will and plan, we need to run to where He reveals mysteries, His Word and Sacraments. In these we find His statement of our status that tells far more than our circumstances.

Luther diagnoses the problem: “The love of man comes into being through that which is pleasing to it.”3 We confuse love and pleasure and believe one necessarily leads to the other. God’s true love pulls us away from looking at our hearts or our circumstances, pleasure or sorrow. It leads rather to where God’s outpoured gifts create life and love. As Luther says, “The love of God does not find, but creates, that which is pleasing to it.”4

Therefore, spiritual health needs the Means of Grace, where God comes to His people. St. Paul warns, “Having begun by the Spirit, are you now being perfected by the flesh? Did you suffer so many things in vain — if indeed it was in vain? Does he who supplies the Spirit to you and works miracles among you do so by works of the law, or by hearing with faith” (Gal. 3:3–5).

Many gifts

Spiritual health means living as joyous children among all the free and unconditional gifts the Father gives for Christ’s sake. The apostle says, “In every way you were enriched in him in all speech and all knowledge — even as the testimony about Christ was confirmed among you — so that you are not lacking in any gift, as you wait for the revealing of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor. 1:5–7). God gives us gifts which, when received by faith, become opportunities for joy, meaningful service and purpose in our lives. The psalmist rejoices, “Your testimonies [O LORD] are my heritage forever, for they are the joy of my heart” (Psalm 119:111).

Through Word and Sacrament — delivered in myriad ways — we receive the forgiveness of sins, life and salvation. You are blessed, kept and beloved children who live in peace (Num. 6:24–26). The Word and Sacraments are found where His people are gathered at the Lord’s altar. It can never merely be our place of work. Along with all the saints, God’s servants receive the benefits of Christ’s suffering, death and resurrection. His servants are restored there, and then God gives even more.

The Father tells us in Proverbs, “My son, be attentive to my words; incline your ear to my sayings. Let them not escape from your sight; keep them within your heart. For they are life to those who find them, and healing to all their flesh. Keep your heart with all vigilance, for from it flow the springs of life” (Prov. 4:20–23). We can wrongly take this as admonition and accusation, but if instead we hear the promise we learn of further gifts.

Amidst our anfechtungen, we tend to focus on evil and “tears have been my food day and night” (Psalm 42:3). But the Lord calls us to His gifts. These are “living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword” (Heb. 4:12). We must, therefore, guard our hearts with all vigilance and “set [our] minds on things that are above” (Col. 3:2) — and that can be deeply enjoyable.

There are so many gifts. Theologians of the cross do not think of prayers as an obligation or a burden. Praying is a gift that children can happily enjoy without ceasing (1 Thess. 5:17). Those who see it as a wish, command or last resort forget the joy of going to Jesus with “our Father.” He speaks of His children’s prayers as a golden bowl lifted before His throne (Rev. 5:8). He does not parse our words for correctness. He sends His Spirit to search our hearts. According to Romans 8:28, even our groans bring answers. Have you noticed how children love to sing? Psalms and hymns and spiritual songs lift the downcast and fill our lives with thanksgiving (Eph. 5:19). The Scriptures are a book of promises, not a self-help manual. Seeking the treasures nestled among the words is an inexhaustible source of joy. Even when two or three Christians seek these gifts together, they are transported to the throne of grace (Matt. 18:20). Helping the broken and distressed is, therefore, not merely keeping the law, it is the opportunity to behold the hidden Christ (Matt. 25:40). The list could (and will) go on for eternity.

Because of Christ’s cross and resurrection, the Father withholds nothing good from His children (Psalm 84:11). Jesus rent the heavens and came down (Isaiah 64:1), that we “may have life and have it abundantly” (John 10:10). Only in His gifts do we find life, health and peace. As Isaiah rejoiced, “I will give thanks to you, O LORD, for though you were angry with me, your anger turned away, that you might comfort me. Behold, God is my salvation; I will trust, and will not be afraid; for the LORD GOD is my strength and my song, and he has become my salvation” (Isaiah 12:1–2).

Spiritual health consists in receiving this gracious salvation and daily drinking deep drafts of God’s gifts: “With joy you will draw water from the wells of salvation” (Isaiah 12:3).

This theological reflection first appeared in the 2021 booklet “A Lutheran Perspective on Well-Being” (LCMS).

1 Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, ed. Harold J. Grimm and Helmut T. Lehmann, vol. 31 (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1957), 40.

2 LW 31:52

3 LW 31:57

4 LW 31:57

In the coming months, you will hear more about the work of LCMS Church Worker Wellness initiative, including new resources and more. Stay tuned to Reporter, The Lutheran Witness and the LCMS Church Worker Wellness site for updates.

“You keep him in perfect peace

whose mind is stayed on you,

because he trusts in you” (Isaiah 26:3 ESV).

Yet our minds wander and our peace is fragmented, sometimes deeply, as difficulties large and small arise from our broken world and the consequences of our own waywardness and frailty. The better path to recovery from turmoil and injury is not going to be by our own strength and clever thinking in an effort to “get over it,” but by sincerely grieving our disappointments, admitting our weakness, and pleading for the grace to walk aright again (or perhaps for the first time).

“Humble yourselves, therefore, under the mighty hand of God so that at the proper time he may exalt you, casting all your anxieties on him, because he cares for you” (1 Peter 5:6-7).