Robin Phillips and Joshua Pauling, Are We All Cyborgs Now? Reclaiming Our Humanity from the Machine. Basilian Media, 2024. 453 pages. Order here.

By Stacey Eising

This new book, co-authored by an LCMS student of theology, offers a solution to our digital technology predicament: life together in the church.

Perhaps you also saw this rather disturbing ad on TV recently: A man is sitting in a diner designing a new website on his laptop. As he types, the bodies of those sitting around him are violently transformed, lurching back and forth as they sprout enormous muscles that distort their appearance and tear their clothes. Strangely, they seem not to notice the transformation. The camera pans to the man’s computer screen, where he has finished creating the website and chosen the domain muscle-club. com. Then, the Squarespace logo comes on screen along with the tagline: “A website makes it real.”

If we are not careful, this is how we can begin to see the world in our digital age. As Robin Phillips and Joshua Pauling argue in their new book, Are We All Cyborgs Now? Reclaiming Our Humanity from the Machine (Basilian Media, 2024), digital technologies, AI and the internet are different in kind from any technology that has come before (like books and table saws) in their tendency to operate as “reality-mediating mechanisms” (20) — lenses through which we see the world and ourselves. Digital technologies can shift us toward certain ways of viewing the world: seeing our real selves as our minds apart from our bodies; believing our identities are chosen rather than given, rooted in what we consume and desire; and viewing knowledge as essentially made up of data points.

Alarm bells have been sounding in many quarters recently about our culture’s smartphone addiction and its ties to mental illness and isolation. Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation, about the epidemic of teenage mental illness that a childhood with smartphones and social media has wrought, rocketed to the top of the New York Times bestseller list last year. Countless similar books, like Johann Hari’s 2022 Stolen Focus and Cal Newport’s 2019 Digital Minimalism, also struck a chord with readers. It is a hot topic: Digital devices have encroached into our lives, filled with algorithms designed to suck us in, all while constantly leeching data from us to sell us more things and draw us in further with tailored content. Recent research has also shown just how much the internet — that ultimate, instant worldwide connector — has paradoxically led to widespread isolation and fragmentation.

The March issue of LW focused on the overt hostility our culture directs toward Christians. However, our context today poses another kind of threat to Christians seeking to live faithful lives: an environment of distraction and consumption so pervasive that it is difficult to resist — indeed, difficult to disentangle ourselves from enough to even realize it ought to be resisted. In their book, Pauling and Phillips argue that doing so is something that Christians should take very seriously.

Are We All Cyborgs Now?, a rigorously researched 453-page tome that draws from philosophy, Scripture, theology and literature, makes two extremely needed contributions to the popular discussion about the internet and digital technology: First, it tackles the issue from an orthodox Christian (in Pauling’s case, LCMS Lutheran) perspective, taking up the theological and anthropological questions behind digital technology rather than just its impact. Secondly, enabled by its orthodox Christian viewpoint, the book goes where many books on the topic do not and cannot: In its final section, “Being the People of God in a Technological Age,” it offers practical advice for Christian life in this context, including suggestions for technology boundaries to set with children (and with ourselves). As Pauling puts it in the introduction, “We want to do more than merely curse the darkness; rather, we want to light a candle” (6).

This sentence highlights what makes the book such a needed contribution to this discussion: As orthodox Christians, the authors are neither shocked by the problems nor in doubt as to their solutions. A world full of things that seek to steal our attention away from Christ is nothing new,1 and the ultimate solution for Christians (Christ and His church) is nothing new either. Even as our technology “nudges humans towards an overwrought sense of autonomy and an accompanying anti-body outlook,” we are already possessed of “a surer foundation,” “the church’s liturgies of life … rooted in the marvel of human physicality, the miracle of the Incarnation, and the mystery of divine self-giving through Word and sacrament,” writes Pauling (161).

The church has the solutions to the problems technology causes. Where the algorithm seeks to push us into repetitive cycles of consumption and isolation, the church sets up a different pattern for our lives, one of life together and of reception of God’s gifts (161). To a culture that has lost any shared narrative or even media source, the church offers the Gospel, “a real, historical story of unsurpassed artistry and truth” that has at its heart “a living person, an embodiment of truth, goodness, and beauty—Jesus Christ, the God who has taken on flesh, overcome death, and reversed our Fall by the indestructible power of his life” (219). Where the internet, AI and our screens downplay our bodies and tell us that “the real person is inside the head or the heart” (162), the church offers a robust endorsement of our physical bodies, complete with a Savior who “did not come to offer an escape from the body but to redeem our bodies” (229).

Among the book’s practical advice is a tip on the arrangement of our homes: We should make things like books, board games and musical instruments easily accessible and central, while keeping TVs and other devices in more inconvenient locations, since often “what is ready at hand will be our default activity” (402). This tip, I think, offers a hint as to why our culture is finding it so difficult to kick habits we know are so destructive. As Pauling and Phillips put it, “For our human desires truly to be formed and shaped towards truth, goodness, and beauty, we can’t just remove the bad things; we must replace them with better things” (409). It is hard to resist overuse of devices that are designed by experts in human behavior to keep you looking at them. More will be needed than disdain for a life mediated through a screen — we need a positive vision of what life ought to look like instead. Only Christianity truly offers the vision of a life that can ultimately satisfy us — even if we only experience glimpses of it here. This is why Pauling and Phillips’ book offers what authors like Haidt, Hari and Newport cannot.

Are We All Cyborgs Now? offers lengthy theological, philosophical and historical discussions that will be of interest to many. However, everyone in the church can benefit from its practical discussions of the relationship between technology and the Christian life. The book also includes a section of guidance for Christian schools and teachers.

Also of note for many of our readers is Pauling’s chapter “Livestreaming Ourselves to Death.” Without condemning churches’ use of livestreaming technologies out of hand, he points out that conversations about such practices need to include the deeper theological questions of “human autonomy and the relationship of the mind to the body, questions of man’s nature and relation to God” (160). Suggesting that the Divine Service can exist in a virtual space may unintentionally offer “catechetical training toward disembodiment,” suggesting that church consists merely of learning facts about God or feeling certain things, rather than actually communing with Him and receiving His gifts in our bodies (163). Pauling provides specific advice for how churches can employ technology in intentional ways, avoiding its pitfalls.

Taking these matters seriously is very important. While the havoc such technologies are wreaking on our children and our society can be shown today by the statistics, they could have been predicted long before by what our theology tells us about the human person. We should remember, however, that the Christian church really does offer the solutions to our world’s problems today, as it has in every age — no matter how big or small, how theological or untheological, they may seem.

As Pauling puts it: “If there is any institution, belief system—or better yet, Person—designed to withstand the onslaught of the digital age, it is the church, Christian doctrine, and Christ himself—the True Human” (189).

1 As Phillips aptly puts it, “Your attention is your most precious resource. That is why everyone from demons to advertisers will try to harness [it] for their own purposes” (369).

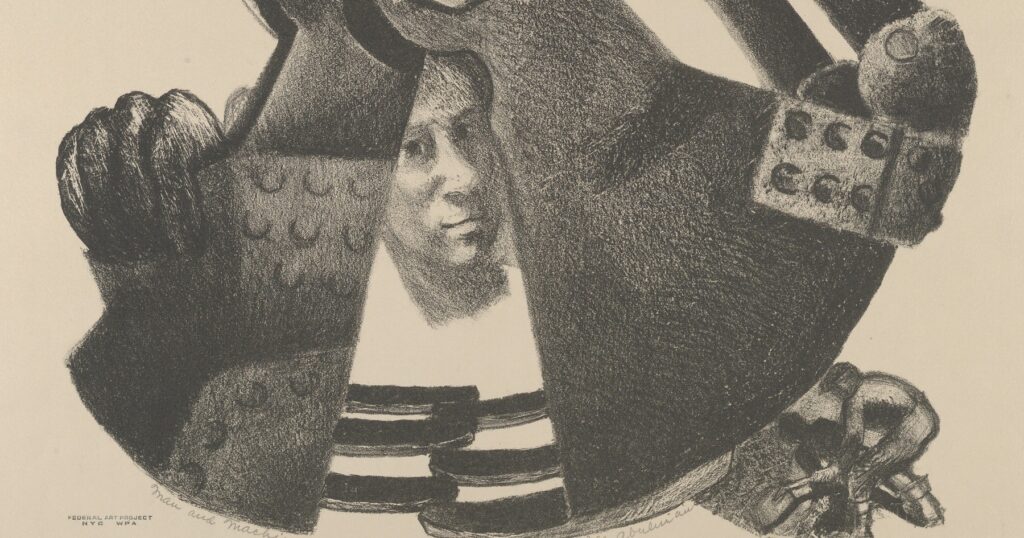

Cover image: “Man and Machine,” Ida Ableman, ca. 1939.

Excellent review! I can’t wait to read this book.

Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be dispersed over the face of the whole earth.” 5 And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of man had built. 6 And the Lord said, “Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do. And nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, so that they may not understand one another’s speech.” 8 So the Lord dispersed them from there over the face of all the earth, (Genesis 11:4–8, ESV, https://ref.ly/logosres/LLS:1.0.710?ref=BibleESV.Ge11.4-8).

Thanks to the internet, we have found a way to “join together” what God had “put asunder.” Ironic that we should be talking about this on a website, isn’t it?

. In the recent past, I found myself falling into the addiction of spending too much time on social media, and it was affecting my moods and thought process. It was taking me further from thoughtful critical thinking into an area of reinforcing opinions based on sound bites, superficial answers, and emotional responses. Much of my early life consisted of just reading books and papers, listening to the radio, processing information with what I felt was an attempt at objectivity. As a Christian, the truths of the Bible remain the foundation of my worldview and are strongly embedded in my thinking. However, as technology pushed us to higher levels of information processing, I found technology deprived me of peace of mind. Long ago, I stopped Facebook. I deleted YouTube, Instagram and X, and now feel free. I would open Instagram and see a Bible verse someone posted, and right before or below, a nasty message or a scantily clad woman. The dichotomy was obvious. Things were on the screen that I had no interest or desire to read. I know my choices are not everyone’s, but my spiritual walk with the Lord and my peace of mind are more important to me. Soli Deo Gloria