In this series, Benjamin Kolodziej will reflect on several figures in American Lutheran sacred music history. This series is based on his new book Portraits in American Lutheran Sacred Music, 1847–1947 (Concordia Publishing House), which will be released in August and is available for pre-order now.

These days, Lutheran students may attend their choice Concordias to prepare them for a life of secular or ecclesiastical service. But this system has not always been in place, and, in the 19th century, educational options were fewer.

In 1864, the Missouri Synod founded the Lehrer-Collegium des Seminars zu Addison, or the Addison Seminary, a few miles outside of Chicago, Ill. Although not the first college in the Synod, and not a “seminary” in the modern sense, it was uniquely charged to train teachers to supply the schools which every Lutheran parish was expected to establish. That is not to say that every graduate became a teacher — some went on to the ordained ministry, while others eventually pursued secular professions.

Addison Seminary was initially intended only for boys. Most enrolled in this boarding school around confirmation age, and would go on to complete the equivalent of high school and a couple years of college, eventually earning a diploma roughly the equivalent of a modern associates degree. But even at this point in the history of American Lutheranism, the church valued sacred music enough to ensure that each teacher was trained in sacred music so he was at least able to serve as an organist, with proficiency to play a Lutheran service.

A Call to Addison

In December 1866, Karl Brauer and his family arrived at their primitive lodgings at the Addison Seminary. He had just been called by the Missouri Synod in convention, with C.F.W. Walther’s support,[1] as the third full-time faculty member of the seminary, and the first whose duties would consist primarily of music education.[2] The 35-year-old, originally from Hessen, Germany, had emigrated in 1850 after his own education in the Lutheran teaching ministry,[3] settling into daily instruction in singing, piano, organ, music theory and violin.

The vocation of the Lutheran teacher at the time, following an older tradition, of which even such a luminary as Johann Sebastian Bach was an inheritor, required that teachers serve as parish musicians, not only playing organ on Sundays, but selecting music and teaching their students chorales from the hymnal. To this end, Brauer tightened the musical curriculum at Addison in order better to prepare graduates as church musicians.

Brauer had installed a Pfeffer organ in 1869, no doubt inspired by Walther’s endorsement of Pfeffer as a builder for the Missouri Synod, thus providing a suitable instrument for students to practice and to play for chapel.[4] Another small practice organ was added two years later.[5]

Enrollment grew steadily, and by the 1870s these organs were only able to supply three and a half hours of organ practice per student per week. To accommodate growing enrollment, the seminary built a new “Aula,” or lecture hall, in which an eleven-rank Pfeffer organ was installed in 1876. Brauer proudly calculated that the three organs would now permit each student four hours a week of practice time. Students were also encouraged to play hymns for daily devotions.[6]

A decade later, acute growth necessitated another, larger organ, completed in 1887 to Brauer’s designs by Carl Barckhoff of Salem, Ohio, a builder who supplied economical and reliable organs.[7] With all of these instruments, Brauer ensured that Addison students would acquire at least some experience on a pipe organ.

Although a few fine organists proceeded from Addison, the institution was not a conservatory, and many students ended up with only the most basic of musical competence. One student recalled the primitive conditions of the school, as well as their daily morning chapel services at which “students would play for the singing of hymns. … Sometimes the singing was accompanied so poorly that even the director could hardly suppress a smile, and he was a stern man.”[8] Ultimately, their parishes might only have a piano, a pump organ, or no instrument at all. (And up until 1905, Addison students learned to play violin in order to lead a service without a keyboard.) Yet, Brauer would inculcate within them a musical vision for which they could strive once assigned to the field.

Brauer’s Choralbuch (1888)

Karl Brauer’s position as a professor in the only teachers’ seminary in the Missouri Synod afforded him a certain visibility which allowed him to promote a concept of sacred music which accorded with C.F.W. Walther’s, endorsing the use of music informed by “old” Lutheran practices.

He wrote regularly for Addison’s periodical, Das Evangelisch lutherisches Schulblatt, reviewing collections of organ music which he commended as being “highly desired by all teachers in our synodical associations, who at the same time have to provide the office of organist.”[9] He consistently recommended music of the greatest composers of the German tradition, encouraging a return to this repertoire, as opposed to the musical styles so prevalent elsewhere in American ecclesiastical practice.

The organist of the 19th century faced a unique array of challenges. In addition to playing service music, they would have had to select the tune for each hymn in Walther’s Kirchen-Gesangbuch (1847), the hymnal itself supplying only the chorale text with a suggested tune. It was incumbent upon the organist to locate the tune, determine if the congregation was unfamiliar with it and, if not, to select another in the same meter from an index in the back of the hymnal. Complicating matters, after a long week of teaching, the organist would often receive the hymns on Saturday, having to select tunes and service music on his day off.

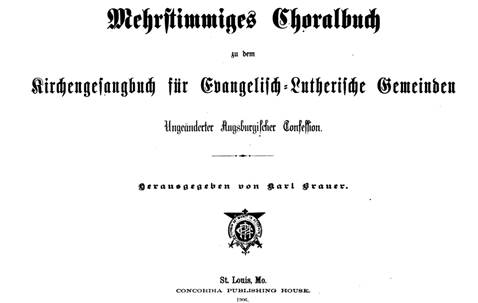

To assist the organist in this task, Brauer edited the Mehrstimmiges Choralbuch zu dem Kirchengesangbuch für Evangelisch-Lutherische Gemeinden, printed by Concordia in 1888. This collection was intended to supply four-part settings for all the hymns in the Kirchen-Gesangbuch. In accordance with Walther’s desire that congregations sing the original, “rhythmic” versions of the chorales, Brauer’s Choralbuch supplied only these lively, robust, Reformation-era versions of the melodies to their native harmonies.

In compiling this volume, Brauer ensured that the students at Addison would have one chorale book from which to play, and that they might learn the same versions of the hymn tunes, thus propagating them uniformly as the students later scattered throughout the country. President Krauss of Addison affirmed the pedagogical purpose of the Choralbuch:

If the congregation is to learn to sing, it must always hear the same melody and harmony; and if a member of the congregation from Baltimore or Omaha is to sing properly and without offense in a Lutheran congregation in Chicago, the organists in Baltimore, Chicago, and Omaha must present the chorales the same way, with one melody, rhythm, and harmony.[10]

Brauer was uniquely situated at Addison to instruct future teachers that they might go forth to present Lutheran hymnody in its most “pure” form. Krauss commended Brauer’s book to the entire church, wishing “that Brauer’s Chorale Book will be used in our synodal congregations and that the right Lutheran tunes will once again become common property of all our congregations!”[11] Indeed, the Choralebuch was utilized widely by organists throughout the country.

Brauer’s Legacy

In December 1889, Addison celebratedBrauer on the 25th anniversary of his installation. The Schulblatt featured Brauer’s portrait on the cover, and President Krauss extolled him for so faithfully executing his vocation:

For 25 years, you have taught our students in all musical disciplines that must necessarily be taught and cultivated at a Lutheran teacher seminary: singing, piano, organ, violin, and music theory. … What kind of spirit and purpose is this which inspired you? It is the sense with which our evangelical Lutheran Church has ever made music and put it at the service of the glory of the living God; it is the spirit that inspires the poet and composer of the hymn “A Mighty Fortress” … the spirit of Luther, in whose writings we find so many wondrous expressions of the great utility and the tremendous power of music.[12]

Krauss mentioned that Brauer still exclusively taught singing and music theory “with unbridled strength”:

Every cantor and organist who has emerged from our seminary over the last 25 years, who now has charge of their own church and school, owes much to your training. No one who disfigures the beautiful things of God by unchurchly organ playing, or by empty sing-song or clitter-clatter, who may labor under the title of “choir director” can blame you for their misdeeds. No, he didn’t learn that from you.[13]

Brauer died on May 12, 1907, at age 76, in North Tonawanda, New York.

Through his organ design in Addison and promotion of the ancient, rhythmic style of chorale singing in his Mehrstimmiges Choralbuch, through his teaching of singing, theory and organ, Brauer conveyed high ideals of sacred music to hundreds of students. Only a few years after his death, the Addison seminary would move to River Forest, where it continues today as Concordia University Chicago, serving as a flagship institution of higher education for the Missouri Synod, with sacred music study integral to its mission.

[1] C.F.W. Walther, “An die betreffenden Glieder des Wahlcollegiums,” Der Lutheraner 23, no. 14 (March 15, 1867): 111. Trans. by author.

[2] Alfred J. Freitag, College with a Cause: A History of Concordia Teachers College (Concordia Teachers College, River Forest, 1964),47.

[3] Carl Schalk, Source Documents in American Lutheran Hymnody (St. Louis: CPH, 1996), 91.

[4] J.C.W. Lindemann, “Die neue Seminar-Orgel, Evangelisch lutherisches Schulblatt 5, no. 5 (May, 1870):152. Trans. by author.

[5] Karl Brauer, [“B”] “Die Orgeln im Schullehrerseminar zu Addison, Ill,” Evangelisch lutherisches Schulblatt 11, no. 11 (November, 1876): 342.

[6] Ibid.

[7] E. Homann, “Die Orgel in die Aula des Neubaus des Addison, Evangelisch lutherisches Schulblatt 22, no. 2 (Zweites Quartel, 1887): 5.

[8] Albert Beck, unpublished “Autobiography,” August, 1960: 14.

[9] Karl Brauer, “Literarisches,” Evangelisch Lutherisches Schulblatt 6, no. 11: 349. Trans. by author.

[10] E.A.W. Krauss, Review of Mehrstimmiges Choralbuch, Evangelisch lutherisches Schulblatt 23, no. 4 (Viertes Quartel, 1888): 182. Trans. by author.

[11] Krauss, “Review,” 182. Trans. by author.

[12] E.A.W. Krause, “Rede zur Feier des Jubiläums des Herrn Prof. K. Brauer,” Evangelisch Lutherisches Schulblatt 27, no. 1 (January, 1892): 5.

[13] Ibid, 9.

Thank you for this informative article about my great great grandfather Karl Brauer. Of note Karl was born in Lißberg Hesse.

I am the son of Wesley Charles Brauer who is the son of Elmer George Brauer who is the son of “Karl” Charles Brauer who is the son of Karl Brauer. All are from the North Tonawanda/ Buffalo New York area.