Concordias seek talented experts who love teaching.

by Roland Lovstad

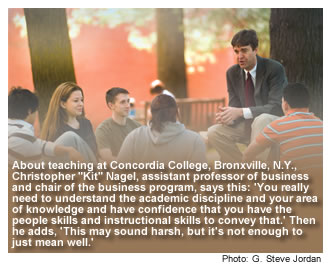

About teaching at Concordia College, Bronxville, N.Y., Christopher “Kit” Nagel, assistant professor of business and chair of the business program, says this: ‘You really need to understand the academic discipline and your area of knowledge and have confidence that you have the people skills and instructional skills to convey that.’ Then he adds, ‘This may sound harsh, but it’s not enough to just mean well.’

Students and professors: a college can’t have one without the other. And both groups need to be recruited. Typically, congregations hear the most about recruiting students for church-work professions or to study at a Christian university. Less is heard about the need to recruit faculty.

Dr. Gayle Grotjan aims to change that. One of her responsibilities as director of cooperative services for the Concordia University System is to spread the “we need you” message to potential faculty. She says the system maintains a central database that can be tapped by all 10 LCMS colleges and universities.

“We are looking for men and women who have advanced degrees, who are Lutheran, and who would be excellent instructors,” she says.

Currently, the system has more than 650 full-time faculty and 800 part-time instructors. As colleges and universities add programs, and as the number of students increases, the need for faculty continues to grow.

“Teaching is our Lutheran tradition,” Grotjan says. “That is who we are.”

Consequently, the Concordias have high expectations for quality teaching, Grotjan says. The system looks for instructors who are experts in their field, but who also challenge students. Other qualities include an ability to relate one-to-one, comfort in sharing one’s faith, willingness to mentor students in their spiritual walks, and the capability to uphold and impart Christian values.

Concordia universities and colleges emphasize teaching. However, Dr. Kurt Krueger, president of the Concordia University System, says Concordia faculty also conduct research. “The best teachers are the most current teachers and probably the ones who do publish their research findings,” he says.

Grotjan speaks of “mining” some 40-plus networks that were identified during a faculty-recruiting strategy session with representatives from the colleges. These networks range from the teachers and administrators in LCMS day schools to campus pastors and retired military.

“We are trying whatever we can to raise up the idea of serving as faculty at a Concordia,” Grotjan says. For more information about teaching at one of the 10 Concordia universities and colleges, visit www.lcms.org/cusjobs or contact Grotjan at (800) 248-1930, ext. 1252.

From Uniform to Academic Gown: It’s a Good Fit

Well-trained and well-educated, retired military officers find the transition to an academic environment a comfortable one.

Well-trained and well-educated, retired military officers find the transition to an academic environment a comfortable one.

Dr. Thomas Cedel, president of Concordia University Texas is a good example.

Cedel was an Air Force colonel when he retired in 1997 after a 26-year career that included assignments in Washington, D.C., tours of duty in Japan and Pakistan, and a stint as the commander of the 19th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Shaw Air Force Base in South Carolina. After retiring, Cedel tried business for a while and then served for four years as dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Concordia University, Ann Arbor, Mich., before becoming president of Concordia University Texas in 2002.

“The fit has just been wonderful!” says Cedel, who finds commonality between the military and the church. “The thread is that it’s all about service. In the military, we serve the people of this country. In the church, in our school, in these positions, we serve God, we serve our church, and we serve our students.

“All the things we learn as we go through a military career are things that are directly applicable to being a faculty member or an administrator at our Concordias—leadership principles, management principles, understanding how to budget, how to plan, how to teach.”

As a university president, Cedel also has an eye toward the kind of faculty he wants. He cites three basic requirements: that they be members of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, that they demonstrate expertise in their field, and that they desire to develop Christian leaders.

“I think one of our biggest challenges as we look to the future is finding people with a Lutheran background— with an understanding of our Lutheran ethos— to fit into our faculty. Second, we need expertise to be able to fill that faculty position, whether it’s English, history, political science, business, math, science, or teacher education. Third, we really look for people that are a fit for us—that understand our mission and that college is more than just courses and majors, but that it’s the whole experience of developing our students as Christian leaders.

“I think one of our biggest challenges as we look to the future is finding people with a Lutheran background— with an understanding of our Lutheran ethos— to fit into our faculty. Second, we need expertise to be able to fill that faculty position, whether it’s English, history, political science, business, math, science, or teacher education. Third, we really look for people that are a fit for us—that understand our mission and that college is more than just courses and majors, but that it’s the whole experience of developing our students as Christian leaders.

“We like research, we like people who do that, but we’re about teaching,” Cedel emphasizes. “If folks aren’t comfortable teaching, if they’re not comfortable interacting with students inside and outside the classroom, then they’re not going to be a match for us.”

At Concordia Nebraska: Called to Teach

If opposites attract, then Dr. John Jurchen and Dr. Kristy Jurchen, both assistant professors of chemistry at Concordia University Nebraska make a good couple.

“She makes stuff, and I take it apart,” says John Jurchen, explaining that his wife’s specialty is chemical synthesis, while his is analysis and theory.

Truth is, this husband and wife have much in common as they talk about their third year of teaching at Concordia. They love teaching and have great affection for the students they teach.

Truth is, this husband and wife have much in common as they talk about their third year of teaching at Concordia. They love teaching and have great affection for the students they teach.

“For people in chemistry there are three destinations: research in industry, teaching at a large research university, or teaching at a small college,” observes Kristy Jurchen. “Knowing from my graduate-school experience that I really loved teaching and interacting with the students, I knew I wanted to be at a smaller college. Concordia happened to have two positions open at the same time.”

John had his career goals in mind much earlier. He has wanted to teach college chemistry since seventh grade. And he wanted to teach at a Lutheran school.

Kristy cites the advantages of a small college: “We know students will see professors who care about the subject, care about learning, care about students. We expect a lot of them, but we will also come alongside them to help them succeed.”

“We would be remiss if we didn’t share our joy about the students we have,” says John. “Almost universally, the faculty say one blessing of teaching here is the students—the individuals who chose to learn with us and study God’s world with us.”

Many students who major in chemistry are bound for graduate school or the health professions. John says the Concordia premedical committee can write confident letters of recommendation because they know their students and interact personally with them in and out of the classroom.

“Our office door is always open for students to come in—and they often do. We have several who stop by just to talk,” says Kristy. Sharing an office with her husband works well because students often get two perspectives on a topic, she adds.

Both John and Kristy reflect a strong sense of Christian vocation—that a person serves God in his or her career or activity. John notes that several times a year the faculty is encouraged to study and discuss the Lutheran understanding of vocation. “I have a vocation as a professor, as a husband, and as a son. My students have vocations as students. We try to model that concept. We begin with prayer and ask God for strength to carry on because sometimes chemistry is very tough.”

“When we are advising students we try to help them figure out what they have been called for and the skills they have been given that prepare them for callings in their own lives,” Kristy adds.

“Students also have the chance to see us as brothers and sisters in Christ,” John observes. “Once or twice a year I lead chapel on campus. That was a powerful witness to me when I was a student—how faculty led in sharing their faith.”

The Jurchens also chose to join a congregation where many students worship. He leads a Bible study and plays trumpet every Sunday, and Kristy works with the altar guild.

Both have experience at large colleges. They met at the University of California, Berkeley, where they received their doctorates in 2003. They conducted post-doctoral studies at the University of Illinois, Champaign, where Kristy also taught chemistry. Kristy earned her undergraduate degree from Knox College, Galesburg, Ill., and John is a graduate of Concordia Nebraska.

Finding True Academic Freedom

Dr. Roberto Flores de Apodaca believes he found real academic freedom when he joined the faculty of Concordia University, Irvine.

“It’s been wonderful!” is how he describes seven years of teaching at Concordia. “It has been an absolute blessing to be here in every regard, especially being surrounded by fellow Christian teachers and administration.” A clinical psychologist by training and a professor of psychology at Concordia, Irvine, Flores taught for 23 years at a public university, finding few people of faith in the social sciences. Considering themselves scientists and above the “muck” that faith represented, they often equated it with superstition.

“All issues and questions come down to faith and the role of faith in one’s life,” observes Flores. At Concordia, faculty are encouraged to pursue their intellectual interests. “All of it is guided and grounded in God’s Word, shaped by our values in the Lutheran faith.”

Flores was a full professor, tenured, and comfortable teaching at a public university. “Then they started working on me,” he says of friends from the Concordia community. They encouraged him to teach at Concordia, and after a year of “nice cajoling,” he and his wife accepted an invitation to a worship service on campus and to meet faculty.

“Then my wife joined in, saying I should consider it, that I’d fit in a lot better,” he says. “I became more open-minded, and finally did it. My personal life and my professional life came together.”

Flores especially enjoys a year-long class with 10 selected undergraduate students. He calls it “a joy” to work with students for an extended time in investigating topics of their choice. One result: a series of professional articles co-authored by the students and Flores.

Concordia’s smaller class sizes and shared sense of ministry allow greater interaction between faculty and students, Flores says. In a field where students often go on to graduate school, Flores and his colleagues encourage both research and applied work, and confidently provide letters of recommendation.

“Through your example, professionally and personally, I think you provide an enormous service to students,” he says. “Through you, they see what is possible for them. How they see you as a person, how you incorporate your faith into your work—that is tremendously helpful.”

The faculty also support each other, Flores adds. He doesn’t see petty jealousies or angling for advancement. While salaries are less than those at public institutions, “how do you put a price tag on being able to worship and work alongside Christian brothers and sisters? We get to infuse our work with our faith,” Flores says.

Flores received his education in New York, earning a bachelor’s degree from Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, and a master’s and doctorate from the University of Rochester.