An art reflection by Edward Riojas on James Tissot's "It Is Finished." This is one installment of a monthly series providing reflections on works of art and music from a Lutheran perspective.

Blessed are the eyes that see what you see! For I tell you that many prophets and kings desired to see what you see, and did not see it, and to hear what you hear, and did not hear it” (Luke 10:23–24).

Sometimes we feel alone. But never should we feel that way while sitting in a church pew, and certainly not during the liturgy. When the pastor prays, “Therefore with angels and archangels, and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify Your glorious name, evermore praising You and saying,” we are reminded that we are “surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses” (Heb.12:1). Visualizing this, however, can be difficult.

Artists have tried at various points to show this company of heaven, to show that there are unseen others who dwell in glory while we struggle here below. Often the result is unabashedly grandiose, and necessarily so. Otherwise, we might feel as if heaven were undersold.

Sometimes, however, artwork doesn’t do such a great job. Combine a good measure of Baroque opulence with a dash of Roman Catholicism, for example, and the result can be a cast of thousands. Christ Jesus Himself will be there. Mary, the mother of Jesus, will be there. There will be untold saints and martyrs and angels. There may be a plethora of popes and church fathers and a crowd of others. But it won’t necessarily include you. Such visions make it seem untouchable, unreachable, unattainable.

Enter James Tissot (1836–1902). He was arguably one of the most unlikely of artists when it came to the divine. Jacques Joseph Tissot, as he was formally known, spent most of his life in his native France. His career included a bit of satirical cartooning for newspapers, but he was better known as a practitioner of the academic style which pulled from classical realism. His parents were dealers in fine fabrics, so it wasn’t much of a leap for him to create paintings of flirtatious high society donned with the latest fashions and fabrics.

Among Tissot’s friends were members of the Impressionist movement. While the artist is sometimes associated with proto-Impressionism, he never embraced Impressionism. Neither did he display his pieces alongside those of his Impressionist friends.

Still, Tissot had a strong following and showed his pieces frequently in the salons of Paris. His success and accolades mounted. Along with the artist’s success, however, came an unfortunate adulterous liaison with a British gal, which ended in her death from consumption.

Sometime after, Tissot claims to have had a vision. Perhaps the piety of his Roman Catholic mother caught up with him. Perhaps it was his sins. At any rate, his former successes suddenly became all too empty. Tissot put things on hold and then made three trips to the Holy Land to make studies of the landscape and culture within its historical context.

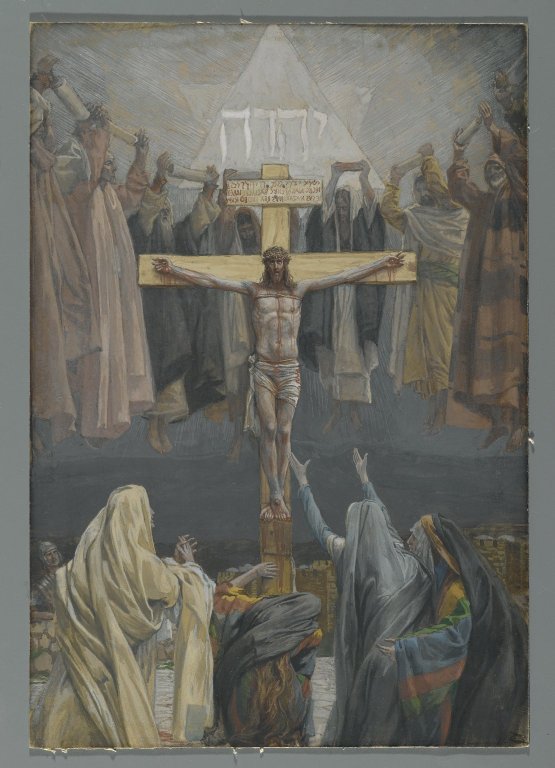

During those trips, Tissot created a massive series of 365 biblical paintings in gouache — a water-based medium — on the life of Christ. “It is Finished” is a painting from that series. Before his death, the artist would work on an additional 80 paintings on the Old Testament.

What sets these gouache paintings apart is not the departure from his previous work. Neither is it the scope of pieces. Rather, it is the archeological clarity, so lacking in earlier works by nearly every other artist, which sets this body of work apart. It is clear that Tissot was not concerned with the grandiosity of classicism or the emotion of romanticism — he was interested in the truth. Where overwrought theatrics and historical inaccuracies once dominated sacred art, Tissot now gave the viewer unvarnished slices of biblical life, based on his own experiences in those places where our Lord actually walked. It may be hard for the modern mind to grasp, but this was entirely new.

These paintings were eventually published in several books, and Tissot regained fame and fortune, albeit from a different audience. The same year that Tissot finished the series on the life of Christ, the artist was awarded France’s highest award, the Legion of Honour.

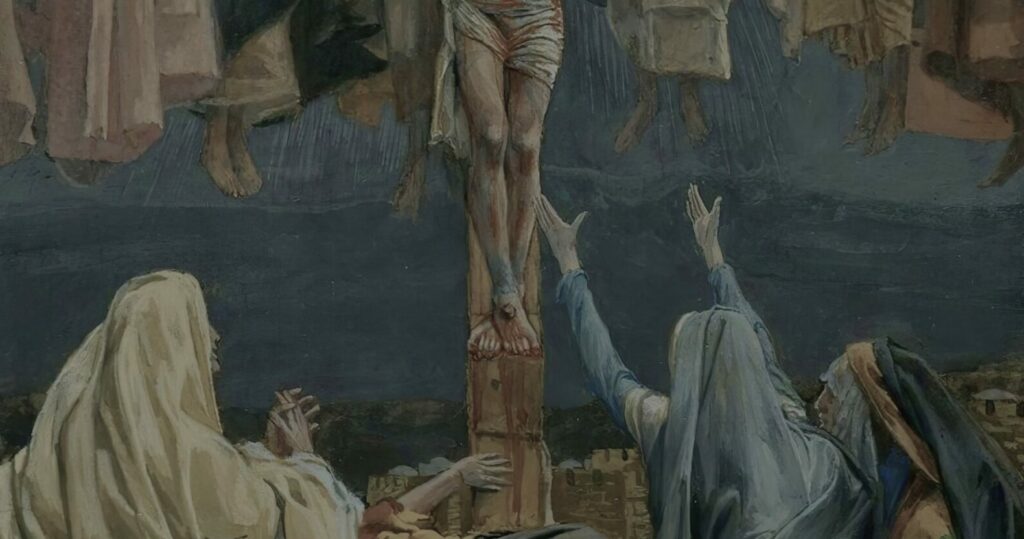

“It is Finished” (Consummatum Est), takes a raw approach that is characteristic of the series. Christ is laid bare — although with a respectful loincloth — before the viewer. The Marys surround the cross. The emotion is appropriate for those watching a Man die before their eyes, and we can feel their grief. The mother of Jesus extends her pleading arms and is comforted by another woman. A flanking woman wrings her hands in lament. Mary of Magdala is placed in her traditional spot at the base of the cross. Her tell-tale hair creeps out beneath a head covering. Her hands clutch the cross itself in a most demonstrative way and foretell the admonition of Christ at His Resurrection, “Do not cling to me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father” (John 20:17).

Tissot then adds a few twists: In confessing that Christ Jesus is the fulfillment of the Old Testament prophets, the artist allows the viewer a peek into heaven. We see the men of old, holding aloft their prophetic scrolls in a great “Amen!” around the cross. They indeed finally see, in glory, that which they so desired to see during their earthly life. There are not billowy clouds to hold them up, yet neither are they subject to the pull of the sin-tainted earth.

Tissot underscores this prophetic element by including a Star of David and the Hebrew word for “Lord.” This hearkens back to the words of David’s psalm, “The Lord said to my Lord …” (Psalm 110:1).

What is more, the viewer becomes part of this tableau. We see it all. We see the prophets. We see the Marys. We see the Lord. We remember that He will never leave us as orphans. We are not alone.

This has to be the funniest thing ever, a Lutheran protestant, with all the baggage of protestant iconoclasm, attempting to comment on sacred art. Hilarious.

Michael, look around the site a bit more. You might find that some of your assumptions about Lutheranism are not quite correct.

Tissot’s entire series is really impressive. Here is another:

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1785/journey-of-the-magi-james-tissot